Inventor John D. Kirschmann: Part I

In June 2019, the North Dakota State Archives received the papers of inventor John D. Kirschmann. For many Midwesterners, the name Kirschmann is instantly recognizable because of the agricultural machinery and products he developed and distributed. For others, like myself (who grew up in a city), the name may be new. As I worked on the Kirschmann papers, I increasingly understood the significance of the technological advancements he facilitated. I also recognized that the agricultural piece is one of many elements in a story of an entrepreneurial genius whose curiosity led directly to improvements in the lives of farmers and city dwellers alike.

Kirschmann was so prolific that his story will require several entries. This first blog post is the beginning of his story...

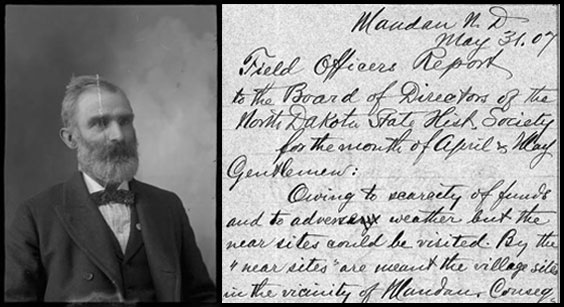

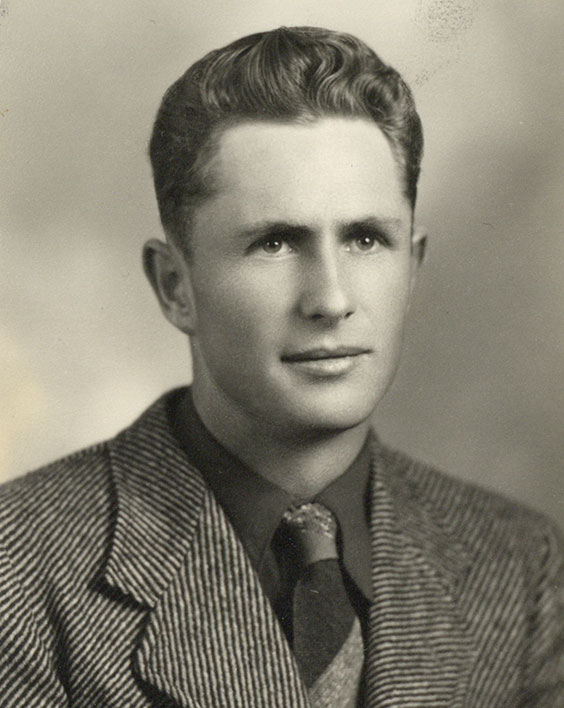

John D. Kirschmann, circa 1941 (11400-00002)

John D. Kirschmann was born and raised in a German-speaking household in Regent, North Dakota, where he attended school until the fifth grade. He struggled in the classroom because of the language barrier, and later noted that he received his basic education from his father in German.

Kirschmann learned best by experimentation and asking questions: an inquisitive child, John sought to understand how things worked so that he could rework and improve them. By age 10, he was able to operate any implement needed to prepare a field for planting, and as a teenager began experimenting with improvements to existing farm machinery. This led to the development of his own machines, which were initially built from scrap metal and used parts.

During his youth, Kirschmann was an active hunter, selling pelts of rabbits, weasels, badgers, and skunks for seed money to start new enterprises. One early business was a turkey ranch that he established and operated while also working for his father.

As a teenager, Kirschmann was already a master at recognizing a need or a problem and constructing solutions from minimal resources. He invented a trip-back scraper to clean between the lugs of a tractor, which he manufactured from scrap iron and sold to neighbors. He also built a water pumping device to irrigate several acres of garden that his father let him develop. To construct the pump and trough, Kirschmann used old tractor pistons, cylinders, and one-gallon oil cans. This invention successfully brought water from a nearby lake, crossed a road, and irrigated the garden without use of solder, glue, cement, or pipe.

As he neared adulthood and prepared to go off on his own, Kirschmann fixed up junk grain drills and resold them. He used that money to buy more parts, from which he built a tractor. With that tractor he raked the neighbors’ thistles, and by the end of the season, had purchased an IHC Farmall tractor. The following year, in 1941, he received 320 acres of land his father had purchased. The land was full of weeds and had not been plowed or farmed. John plowed half of it, planted wheat, and had a great yield that year.

As the years continued, Kirschmann acquired farm land and businesses, becoming an Oliver Machinery Dealer and a Chrysler Plymouth dealer in Regent. In establishing the Plymouth dealership, Kirschmann was the architect and construction supervisor. He invented a bricklaying machine to speed up the process after the bricklayer quit. In a few years, when the Oliver self-propelled combine came out, Kirschmann Motors sold more than any other Oliver dealer in the United States.

Kirschmann Chrysler Plymouth Dealership, Regent, ND (11400-00004)

Kirschmann’s resourcefulness extended beyond his business career into his personal life. During World War II, while the family remained on the farm, John moved into Regent. He needed a home and decided to build one out of materials that did not require a permit. He acquired and constructed his home entirely out of 40” x 40” sheets of glass, 4” strips of oak flooring, ½” thick plywood, a few nails, and brass screws. He then constructed five Federal Housing Administration homes for the garage and farm workers. One of the five homes was a brick house laid by the machine Kirschmann had developed to construct his dealership. Examiners and residents were astonished by the workmanship of the home and how accurately the bricks were laid (they did not know about the machine). The bricklayer in Regent was speechless after the machine was used to construct a large, five-bedroom ranch home for the Kirschmann family in Regent.

If you are interested in learning more, look for the next installment in this series this fall.

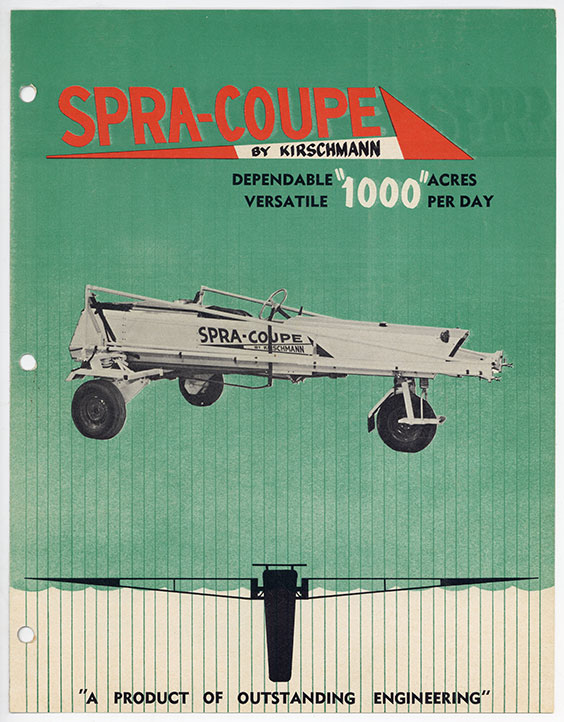

Advertisement for Kirschmann’s “Spra-Coupe.” Look for more information on this invention and its impact on North Dakota in the next blog installment. (11400)