A.C.O. Silos in Barnes County

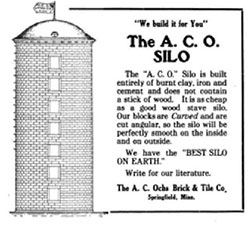

Occasionally, when evaluating farmsteads for historical significance and eligibility for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, even an ordinary farmstead will have a unique or unusual feature. Such is the case in northeast Barnes County, where there are at least two A.C. Ochs Brick & Tile Co. brick silos seen on two separate farmsteads in Noltimier Township. It’s easy to distinguish the silos because the brand name “A.C.O.” is stamped on the exterior, just under the roof. These silos have roofs of domed sheet-metal with a prominent metal ventilator, are accessed by a single door, and have metal ladders that lead to a round opening. They were commonly constructed in the Midwest from approximately 1910 to 1945.

A.C. Ochs Brick & Tile Co. began when Adolph Casimir Ochs, known as “A.C.” Ochs opened the A. C. Ochs Brick and Tile Company in Springfield, Minnesota, in 1891. Ochs and his company began making smooth-face brick in 1910, supplying face brick for many buildings in Minnesota and South Dakota. After World War I, the demand for smooth brick for use as vertical siding increased. Ochs’ company met the demand by opening a plant in Minneapolis, where his brick was used to build several buildings on the University of Minnesota St. Paul and Minneapolis campuses.

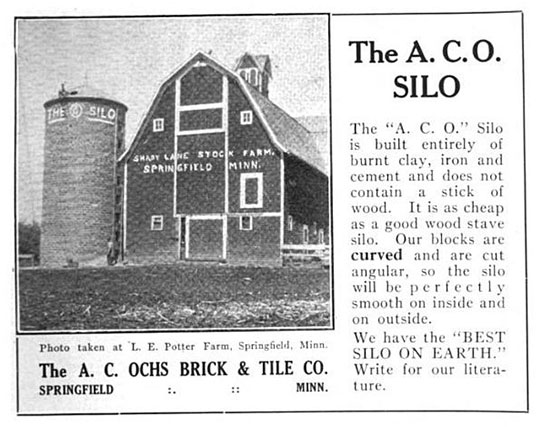

When the Great Depression hit, Ochs’ company turned to making brick silos entirely of burnt clay, iron, and cement—completely without wood. Bricks were curved and radial-cut in an angle so the silos were smooth on both the interior and the exterior with few air spaces to retain heat: a unique method of construction for that period. The silos in Barnes County appear to be of this style, constructed after the Great Depression.

Advertisement, date unknown. Source: “City of Springfield: Historic Context Study,” City of Springfield, Minnesota, June 11, 2011.

A.C.O. silos became common throughout Minnesota and other portions of the Upper Midwest. Ochs’ silos were also built in Wisconsin, Iowa, and the Dakotas, since Ochs hired laborers to construct his silos in other areas where the need arose. It is likely the bricks were transported by rail if the customer was located outside of Minneapolis or Springfield. Advertisements for the A.C.O. silos touted they were as “cheap” as a wood-stave silo but would not rot.

The silos in Barnes County are historically significant as pristine examples of brick silos constructed by the A.C. Ochs Brick & Tile Company. Although the silos were common in Minnesota for three decades, examples of these silos are not prevalent in Barnes County, where many historic-age silos are removed from farmsteads to be replaced by modern steel corrugated grain bins.

Advertisement, date unknown. Source: Minnesota Bricks

A.C.O. silo in Noltimier Township, Barnes County. Photo by Julia Mates/Chelsea Stark, July 20, 2016 SHSND SITS 32BA298

A.C.O. silo in Noltimier Township, Barnes County. Photo by Julia Mates/Chelsea Stark, July 20, 2016 SHSND SITS 32BA299

Sources: Minnesota Bricks, “A.C.O. Silos in Eastern North Dakota,” http:// www.mnbricks.com/aco-silos-in-eastern-north-dakota; The Clay-Worker, Vols. LIX–LX (Indianapolis: T.A. Randall & Co., 1913); City of Springfield: Historic Context Study, Prepared for the City of Springfield, MN, June 11, 2011.