At the State Archives, We Want To Know You Better!

Take the time to fill in the State Archives’ survey and help us serve you better.

The State Archives has launched a short demographic survey, the first in a series, and we invite you to participate! As stewards of the documentary history of North Dakota and its people, we want to know the people we serve, how we can improve our services, and how we can bring new interest to the wonderful world of archives and historical research.

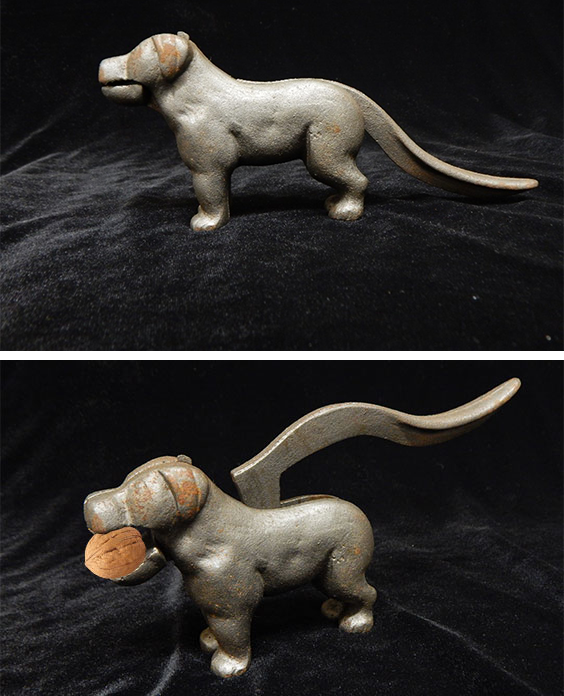

The State Archives’ resources can help patrons solve genealogical mysteries.

Our overarching goals are to get better acquainted with those we serve and increase services and outreach to grow all audiences. With that in mind, we’ve compiled a list of reasons for why getting to know our clientele will help us reach these goals:

1. Communication: We can devise the best strategies to communicate who we are and what we do.

2. Engagement: Those who have fun together learn better together. We can share our love of history with our users in more effective ways.

3. Collection description and access: We can prioritize the identification, description, and digitization of items and collections of significant research interest.

4. Technology: We can utilize technologies that are familiar to our audience to provide better access to our collections as well as identify and assist with less familiar technologies.

5. Programming: We can design programming to engage our current patrons and draw in groups of people not previously reached.

6. Collection acquisition: We can focus on acquiring collections that align with the research interests of our users and identify and fill topical gaps in our collections.

7. Overall experience: We want visitors to have fun here (and on our website), to use our resources to solve mysteries, answer questions, and formulate new ideas. We want the journey of conducting research and finding information to be as streamlined as possible. As archivists, we are proud of the history we get to work with every day and want to share our love of history with everyone, whether they are virtual or on-site, a first-time visitor or a regular. We truly believe that history is created by everyone, and that history is for everyone.