A Work in Progress: Refining the State Museum Collections

Museums continuously accept new objects for their collections. They must also re-evaluate their existing collections, identifying those items that are redundant, lack documentation, or don’t meet their mission. Instead of holding on to items taking up valuable space, museum staff will help make room for new objects by looking for other museums where the objects would be more relevant.

Over the years, the State Historical Society has been able to give artifacts to other museums in North Dakota and across the country. A thresher, our third one, was taking up a lot of our storage space, so this was sent to the South Central Threshing Association in Braddock.

The South Central Threshing Association received this circa 1900 thresher from the State Historical Society.

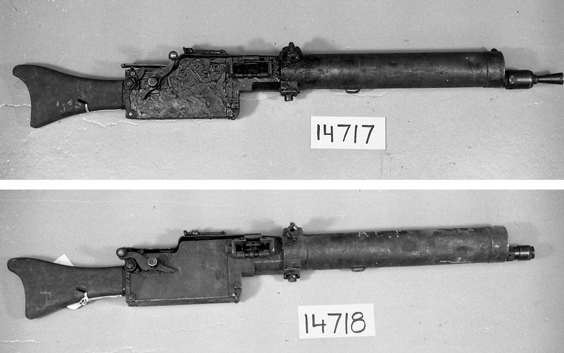

It also made sense to donate two World War I German machine guns. Not only did we already have one on exhibit, but these two were incomplete, would never be displayed, and were taking up much-needed storage space in our gun vault. Due to Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) regulations, there are only limited museums or organizations that are allowed to possess machine guns. We first offered to return them to the original donor, the North Dakota Office of the Adjutant General. We next offered them to the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. They were very pleased to be able to add these guns to their museum.

We donated these German machine guns to the National WWI Museum and Memorial.

In turn, we have accepted artifacts with a strong North Dakota connection from other museums. This 1884-89 Dakota National Guard uniform was offered to us from the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in Madison. The brass buttons on the coat and hat feature the seal of Dakota Territory and “Dakota N.G.” While we are not sure who owned these items, they are a unique example of the territorial National Guard’s uniforms. Similar ones do not exist in any collection in North Dakota or South Dakota. Given its rarity, we decided it would be an important addition to the state’s collections as an example of an early National Guard uniform.

Dakota National Guard uniform coat and kepi cap. SHSND 2001.48.1-.2

Recently, we accepted an Icelandic askur (covered eating bowl) from the Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum in Decorah, Iowa. This askur has a very detailed history. It was originally owned by the Rev. Hans Baagøe Thorgrimsen who emigrated from Iceland in 1872. He served Norwegian and Icelandic congregations in Mountain and Grand Forks. The vessel’s Icelandic origins meant that it was outside the typical collecting scope for the Vesterheim, but the owner’s North Dakota connections made it a very interesting addition for our collections.

This Icelandic askur was a gift from the Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum. SHSND 2022.60.1

These five ballot boxes with limited documented history were offered to us from the McLean County Historical Society Museum in Washburn. We already had similar items; however, we accepted the ballot boxes for educational use at the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse State Historic Site in Jamestown. Since these are educational props instead of artifacts, the ballot boxes can be used in programming and made available for audiences to touch, open, and use as innovative learning tools.

Five ballot boxes from the McLean County Historical Society Museum have found a new home at the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse State Historic Site.

Moving forward, we are continuing to evaluate our collections, looking for new homes for items that have limited North Dakota history or are overrepresented in the state museum collections. We are also open to accepting items from other museums that will further help us tell the story of North Dakota and the people who live here.