Swing Your Partner: High-Stepping Recent Museum Acquisitions

The State Historical Society of North Dakota’s Audience Engagement & Museum Department has accepted several interesting donations to its collections over the past few months. Let me take you on an unintentionally all-dance and music tour of these.

For starters, we had a sudden run of offers, which included square dancing items. By “sudden run,” I mean two donations. Which doesn’t seem like a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice.

The first donation was a collection of items from the Belles ‘N Beaux square dance club.

Belles ‘N Beaux square dance club of Burleigh-Morton counties was formed in 1959 and is still in operation. Several hand-painted items were accepted. These include a wooden wall hanging by E. Roswick, a banner of the Belles ‘N Beaux square dance club and a felt hanging waste bin from 1978.

Delightful artifacts related to the square dancing tradition of Belles ‘N Beaux. I personally aspire to the energy of the dancers in the image above. SHSND 2022.00035.00001-.00003

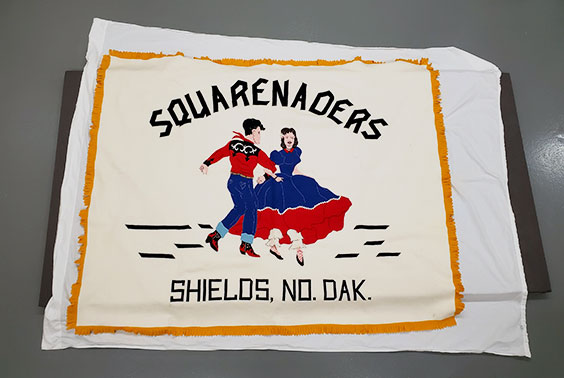

The second donation from the wonderful world of North Dakota square dancing was a Squarenaders tapestry from the community of Shields. The donor’s mother, Alice Ternes, was one of the original Squarenaders when the club started in the 1960s. She recalls that the Catholic priest from St. Gabriel’s parish started a square dance club with and for the people of Shields, as there wasn't any type of entertainment in town at the time.

Alice and her husband, Aloys, scheduled their farm work to allow them to square dance as often as possible. She remembers how some club members went to friends’ houses (usually neighboring farmers), strongly encouraging them to join and learn the dance. Initially hesitant, many neighbors were surprised when they were able to learn the steps and really enjoyed the activity.

Unfortunately, the Shields dance hall where the Squarenaders hosted their events burned down in 2002. But Alice still recollects that the smooth wood floors in the hall, where this banner below also likely hung, were perfect for dancing.

This large banner likely hung in the Shields dance hall, overlooking the whirling Squarenaders. Note the neat 3D elements, like the raised lace. SHSND PA-2022.094

To help fill out our collection, the State Museum is now looking for donations of square dance dresses, skirts, and suits worn by people who kicked it up over the years with any of North Dakota’s square dance clubs.

Speaking of musically related items, the final recent acquisitions I’ll tell you about are a Mandan High School Band cape and a Mandan Elks Band jacket. The cape and jacket belonged to the donor’s aunt Evelyn Stastny, who graduated from Mandan High School in 1949. In addition to playing clarinet in the Mandan High School Band, she was also in the Mandan Elks Band. She joined because it was a bit of a family affair—her father, Edward Stastny, was also a member of the Elks band.

Evelyn Stastny’s uniforms from her days playing clarinet with both the Mandan Elks Band, left, and the Mandan High School Band. SHSND PA-2022.080

If you are interested in donating objects to the agency’s museum collection, please get in touch. You can fill out a donation questionnaire at this link: Potential Acquisition Donor Questionnaire - State Historical Society of North Dakota. We can’t wait to hear from you!