Documenting the MHA Nation: Marilyn Cross Hudson Collection Opens to the Public

Here at the North Dakota State Archives we are thrilled to announce that a lifetime of research and writing by tribal historian Marilyn Old Dog Cross Hudson has been processed and is now open to the public. The collection includes research, manuscripts, articles, working and subject files, historical records, photographs, and other materials created or collected by Hudson. Major subjects include tribal and oral histories of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, as well as stories of Native American veterans, rodeos, and ranching, and of the Cross family. The collection also features records, histories, and photos of Elbowoods High School and the city of Parshall, North Dakota, Hudson’s home from 1953 until her death in 2020.

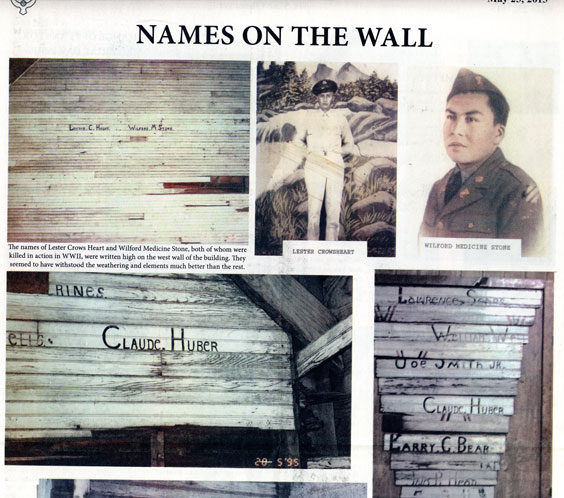

In this May 25, 2015, article from the Six Star Observer, Marilyn Hudson wrote about the names of World War II servicemen recorded in the Elbowoods Community Hall. Hudson, a prolific author, conducted extensive research for her published work. Both her sources and final articles are included in the collection.

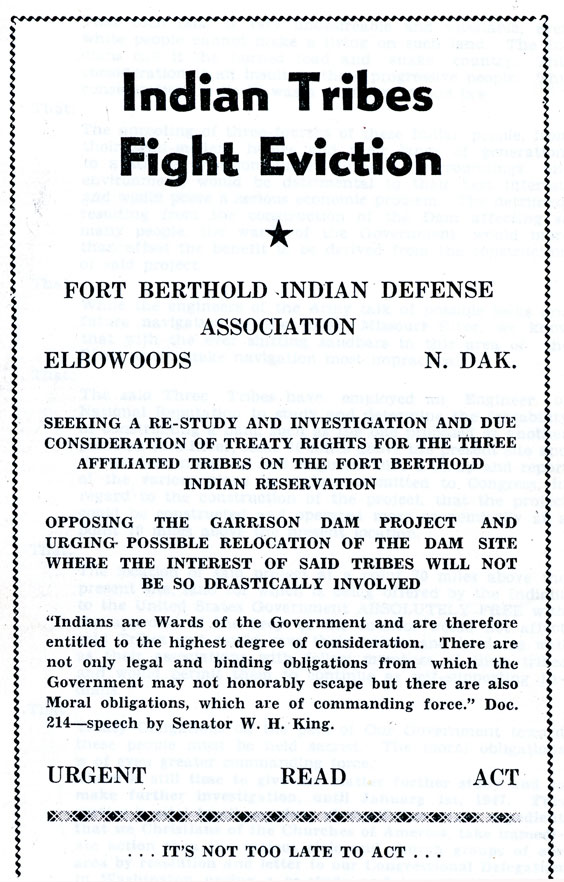

Central to the collection are records of tribal, state, and federal government proceedings related to the construction of the Garrison Dam and its impact on the MHA Nation. The collection chronicles all stages of the project, from initial planning to completion of the dam. Significantly, it documents a wide range of efforts to stop the project, which necessitated the flooding of homes and farms and the relocation of hundreds of families. After the dam’s completion, Hudson carefully recorded its long-term effects on the people of the Fort Berthold Reservation.

One of many documents in the Marilyn Cross Hudson Collection that preserves the record of Garrison Dam opposition, this booklet was produced by the Fort Berthold Indian Defense Association in 1946 to galvanize resistance and encourage further study. SHSND SA 11517-0001-040-00001

Hudson’s collection represents the most comprehensive series of tribal records at the State Archives and includes the correspondence and writings of Martin Cross, Marilyn’s father and long-time tribal chairman and council member. Bringing the historical documents to life are photographs, oral histories, and published articles by Hudson about life in the Missouri River bottomlands before the construction of the dam and after the flooding of the area.

Among numerous topics, Hudson’s collection documents Elbowoods High School activities and student life, including the 1951 Elbowoods Warriors High School basketball team. Back row (left to right): Eldon Jones, Leander Smith, Larry Rush, Norman Baker, Arnold Charging, Tony Mandan, and Coach Richard Washington. Front row (left to right): Leroy Yellowbird, Leonard Eagle, Russell Gillette, and Evan Burr Jr. SHSND SA 11517-00009

Born in 1936 in Elbowoods, Hudson graduated from high school there in 1953. Her college education and professional career took her across the country until she accepted a position with the Bureau of Indian Affairs working at the Fort Berthold Agency and returned to North Dakota. Hudson retired from federal service in 1992 but stayed active in cultural and historic preservation as well as in the promotion of the state. She served as administrator for the Three Affiliated Tribes Museum in New Town and received the North Dakota State Historical Society’s Heritage Profile Honor Award in 2009. Hudson’s legacy in the state endures through her writings, organizational work, and the memories of those who had the privilege to know and work with her.

Hudson collected historical photographs as well as more modern images in her quest to document events for posterity. Pictured here on All-American Indian Day in New Town, North Dakota, are Martin Cross, Sam Meyers, and Mary Louise Defender. The two men on the far right are unidentified. SHSND SA 11517-00045

Hudson’s passion and love for the history of her people and state is reflected in the breadth of topics she researched and wrote about and in her meticulous gathering of primary and secondary sources. Her collection provides insight into the experiences and lives of members of the Three Affiliated Tribes and is an invaluable resource for current and future generations.

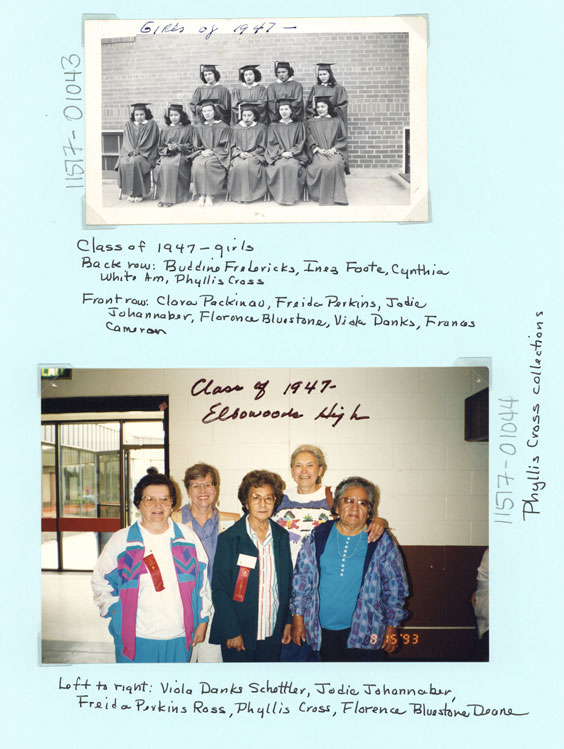

Members of Elbowoods High School’s Class of 1947 at their graduation (above) and at their 50-year reunion (below). Hudson thoroughly documented the people, places, and events in her collection to preserve history. SHSND SA 11517-01043-01044

The public can view the collection at the State Archives in the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum in Bismarck. For more information, contact us at archives@nd.gov.