Marking Women’s History Month in the Archives

March is Women’s History Month. What better way to celebrate than to explore the State Archives’ collections on the prominent women connected to North Dakota. These collections include journalists, pioneer settlers, and trailblazers in the political history of the state, as well as the records of organizations devoted to women. All make the State Archives a great resource for researching women’s history, especially for students considering a possible National History Day project.

One of the eminent women with North Dakota ties who has a collection of materials housed in the Archives is Era Bell Thompson. Thompson grew up in Driscoll, where her family was the only African American family in the small community. She attended the University of North Dakota and Morningside College in Iowa, later becoming an editor at Ebony, the magazine devoted to Black culture and issues.

Era Bell Thompson and Jack Vantine at the Ebony magazine offices in Chicago, November 1972. SHSND SA 11118-00013

The Era Bell Thompson Papers (MSS 11118) at the Archives contain one foot of material related to Thompson’s life and work. Correspondence, family-related materials, some photographs, as well as tribute items, clippings, and published articles showcase a life well lived. Among her accolades, she received the Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Award in 1976.

Another great resource for women’s history is the Alice Kennedy Dahners Papers (MSS 11083). This collection was Dahners’ contribution to the North Dakota Federation of Women’s Clubs Pioneer Mother Biographies project. The project chronicled the stories of married women who lived in North Dakota prior to 1889 through handwritten or typed biographies. This material enriches our understanding of women’s lives during the territorial and early statehood period as well as the struggles these pioneers faced.

Women who have participated in the North Dakota political scene are also represented in the Archives’ holdings. One example is the Nielson Family Papers (MSS 10107), which contain the papers of Minnie J. Nielson, who served as state superintendent of public instruction from 1919-1927. Nielson’s election to that office was remarkable, given that she was the only candidate not supported by the Nonpartisan League (NPL) to win when the NPL swept all other statewide elections in 1918. Her rise to the position is significant because it came at a time when women were mostly shut out from positions of leadership in American politics.

Minnie Jean Nielson portrait. SHSND SA 00117-00032

Minnie and her sister, Hazel, were both involved in their community, serving with the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, as well as being active in several organizations, including the American Legion Auxiliary, the North Dakota Federation of Women’s Clubs, and Delta Kappa Gamma, a society for women educators. The collection contains materials related to Minnie’s service with the Public Instruction Department and her later work with the Teachers’ Insurance and Retirement Fund, which also makes it a great resource for people researching education in North Dakota.

Organizations for women are another important focus of our collections. Researchers can access several organizational record collections in our holdings on women’s groups. One of these is the Women’s Christian Temperance Union of North Dakota Records (MSS 10133). The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is a major organization devoted to abstinence from alcohol and was one of the groups involved in the passage of the 18th Amendment, which ushered in Prohibition in the United States.

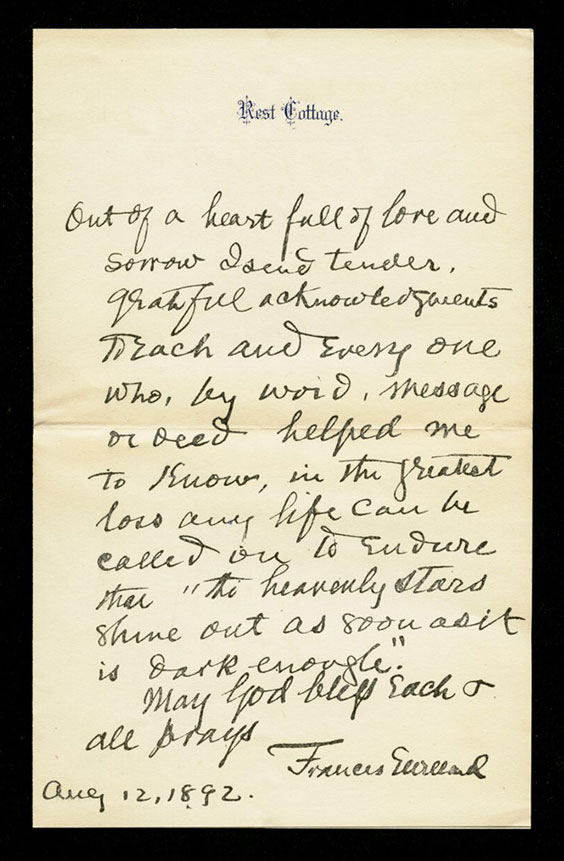

The WCTU collection includes records related to annual conventions, local chapters, promotional materials, scrapbooks, audiovisual materials, and other items pertaining to its activities in North Dakota. One item in the collection, shown below, is an August 12, 1892, letter written by Frances Willard, national president of the WCTU. In the letter, penned shortly after the death of her mother, Mary, Willard expresses her gratitude to members for the assistance they provided during a difficult time.

SHSND SA 10133-p01

As you can see, all of these diverse collections are wonderful resources for learning about and researching women’s history in the State Archives. If you are a student, or know a student interested in women’s history and looking for a National History Day project, consider having them check out our holdings and drop by to do some research. With Women’s History Month upon us, let us use this time to reflect on the contributions women have made to the history of our state and nation.