Monitoring Erosion and Slumping at Double Ditch Indian Village State Historic Site

Double Ditch Indian Village State Historic Site is one of the most spectacular archaeological sites preserved on the northern Plains. The village was occupied for nearly 300 years (1490-1785) by the Mandan people and was a regional trading center. The site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its historic significance. It’s an amazing place to visit!

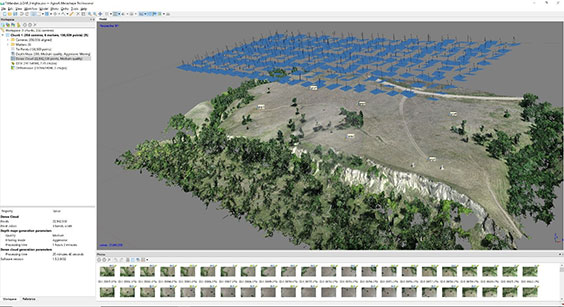

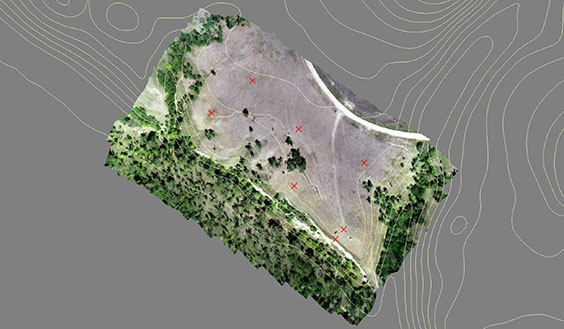

Fortification ditches, earthlodge depressions, midden mounds, and the walking trail present at Double Ditch Indian Village State Historic Site are visible in this image captured by an uncrewed aerial vehicle operated by agency staff in August 2025. View is to the east in this image.

Fortification ditches, earthlodge depressions, midden mounds, and modern features present at Double Ditch are visible in this image captured by an uncrewed aerial vehicle operated by agency staff in August 2025. View is to the northwest in this image.

Visited by thousands of people annually, Double Ditch has been a North Dakota state historic site since 1936. The village has a deep cultural connection to the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation. Following the catastrophic 2011 flood of the Missouri River, the State Historical Society of North Dakota became increasingly concerned about the impact of erosion at the site. Large sections of river terrace edge had shifted in a process called rotational erosion. This erosion destabilized the bank, threatened a large portion of the site, including parts of the public walkway, and exposed numerous burials.

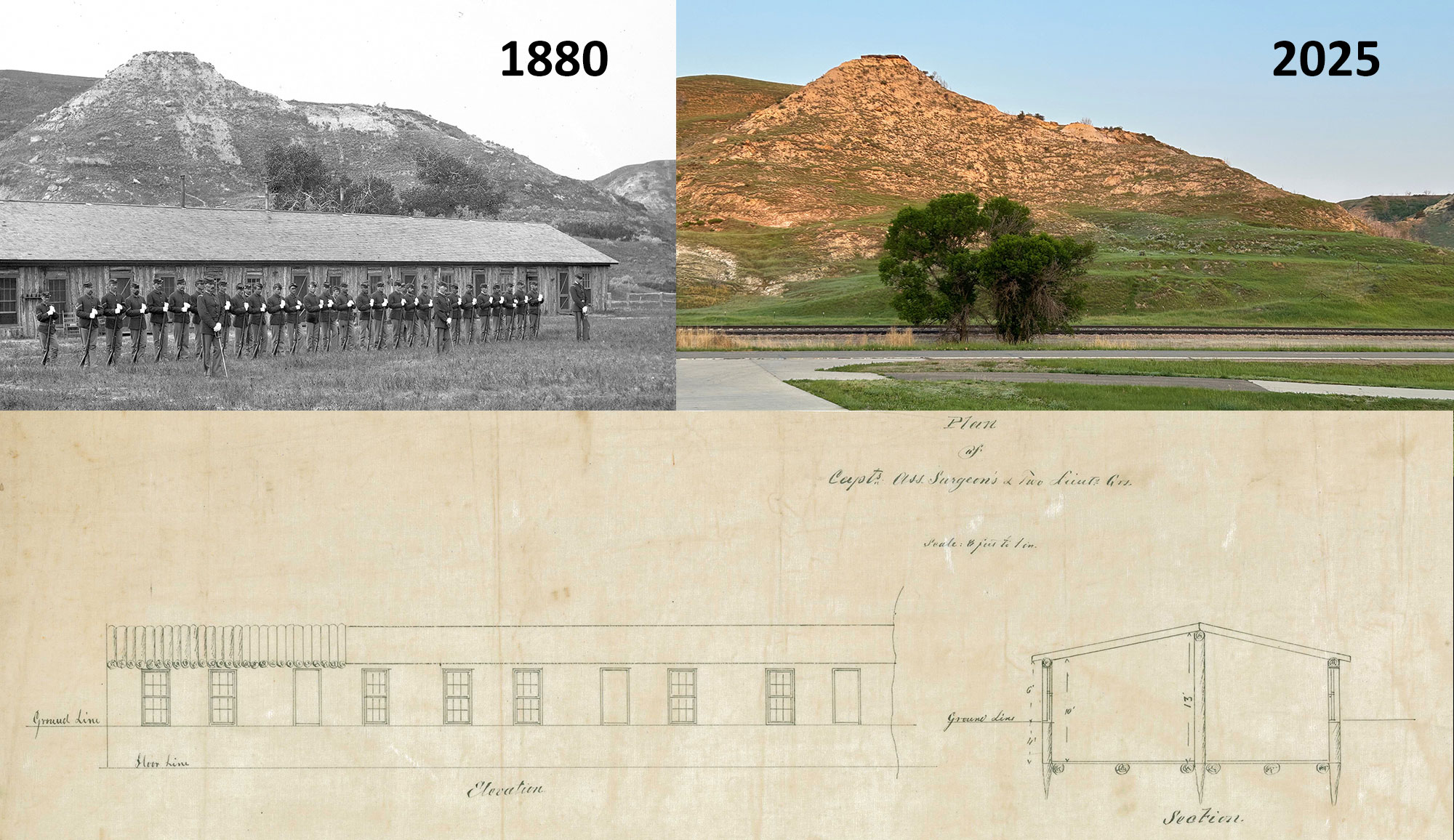

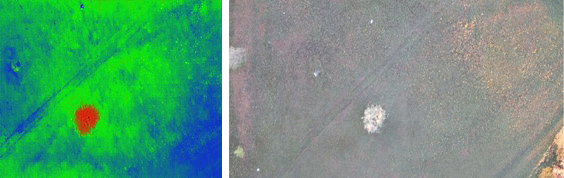

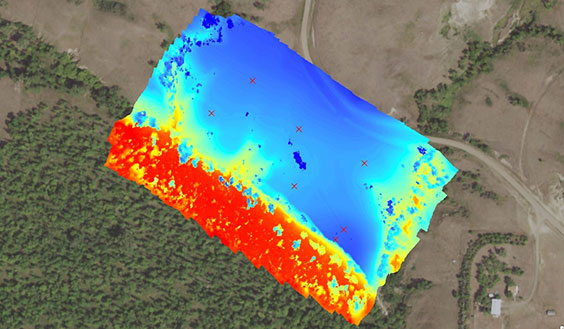

Aerial image of the slumping (rotational erosion) of the bank at Double Ditch captured by agency staff in November 2013.

The State Historical Society partnered with the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, the North Dakota Legislative Assembly, and other entities to address this critical threat. Left unaddressed, erosion would have continued to advance deeply into the village, causing severe damage. An engineering plan was developed and put in place to stabilize 2,000 feet of the riverbank from the effects of the 2011 flood. Appropriations made in 2013, 2015, and 2017 by the North Dakota Legislative Assembly moved this important project forward to save Double Ditch from further damage. Bank stabilization began in July 2017 and lasted about five months. The State Historical Society and the MHA Nation leadership cooperated to follow state laws and recognized cultural practices of the Mandan people while completing this sensitive work. Archaeologists from the State Historical Society were on hand daily throughout the construction period, monitoring all earthmoving activities.

The immense scale of the area in need of stabilization at Double Ditch can be seen in this drone image taken by Dwayne Walker in August 2017. View is to the north.

Agency staff captured this same area by drone in October 2018 after extensive bank stabilization and landscaping. View is to the north in this image.

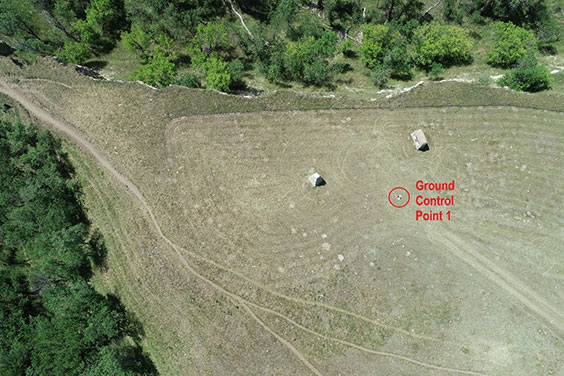

In 2023, State Historical Society staff and visitors to Double Ditch noticed areas of slumping along a walking path and terraced area that was within the previously stabilized area. Archaeology & Historic Preservation Department team members immediately began to monitor the area through regular visual inspection and began documenting the progression of the slumping using uncrewed aerial vehicles (drones).

Drones have allowed us to document the extent of this dramatic slumping from the air and to consistently make detailed measurements on the length and breadth of the cracks that now cross the terrace at Double Ditch. Unfortunately, these cracks are quickly growing and represent a threat not only to the previously stabilized area but also to the undisturbed village features on-site. There is a significant possibility that the village features could be profoundly and disastrously affected if these cracks are left unaddressed.

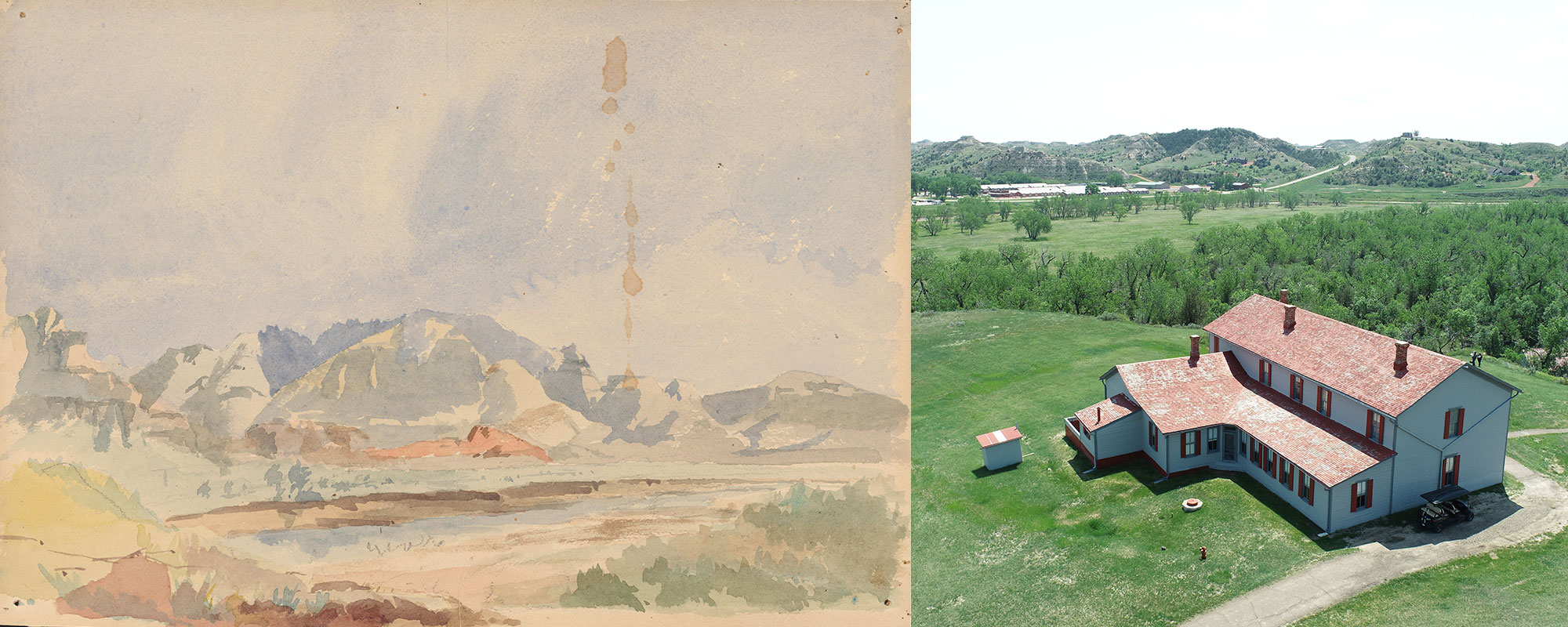

Cracks in the pedestrian path caused by slumping at Double Ditch, March 2024.

The same large cracks are seen on the pedestrian path and a slope close to the WPA shelter at the state historic site in this drone image. This aerial image was taken by agency staff in May 2024.

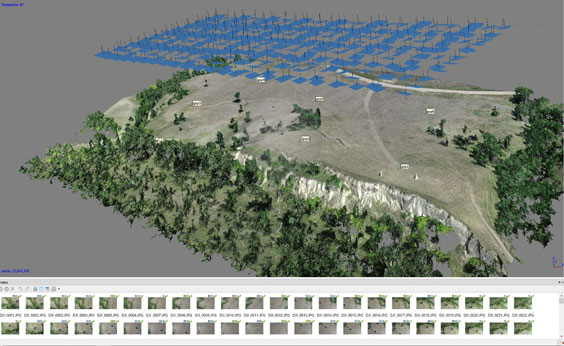

To determine how quickly the slump at Double Ditch is progressing, we needed to look below the surface. Beginning in December 2024 and January 2025, a geotechnical drill team began to install an array of sensitive instruments to tell us how quickly the slump movement was occurring beneath the ground surface. These instruments, called vibrating wire piezometers and slope inclinometers, are used to measure water pressure and lateral movement within the 75-foot-deep holes they’re installed in. Additional instruments were installed in August 2025. These instruments will help us better document the extent of the erosion and slumping. State Historical Society staff will also continue to monitor the area from the ground and the air, partnering with the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, the North Dakota Legislative Assembly, and preservation groups to use all available information to address the threats posed to this important place.

Major slumping cracks at Double Ditch and a geotechnical drilling rig are visible in this drone image taken by agency staff in December 2024.

Drilling personnel collect soil samples in January 2025 (left) and August 2025 (right). There was a 100-degree temperature change between these pictures!

Large cracks in the pedestrian path and the location of geotechnical instruments monitoring ongoing slumping (indicated by yellow posts) are seen in this drone image taken by agency staff in August 2025.