Put a coat on it? The Ins and Outs of Repainting Buildings at State Historic Sites

As a site supervisor, I am entrusted with the care of two historic state properties in Bismarck: the Former Governors’ Mansion and Camp Hancock. These two sites comprise four historic buildings, each with well over a century of paint on the exterior. Time, weather, and people all take their toll on surfaces, which need repainting from time to time. When this occurs, we do not necessarily match the color of paint on the surface because paint fades, and colors change with age. Instead, we strive to match the structure’s historical paint colors.

As supervisor of the Former Governors’ Mansion and Camp Hancock state historic sites, my job entails a lot of paint!

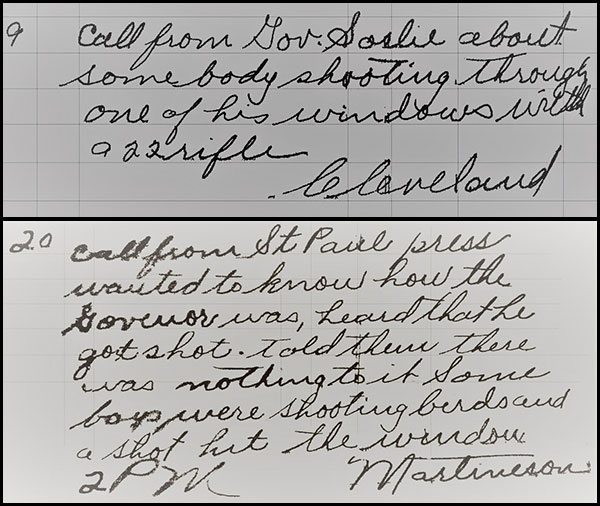

Chipped paint on the back porch of the Former Governors’ Mansion exposed the original 1884 maroon color.

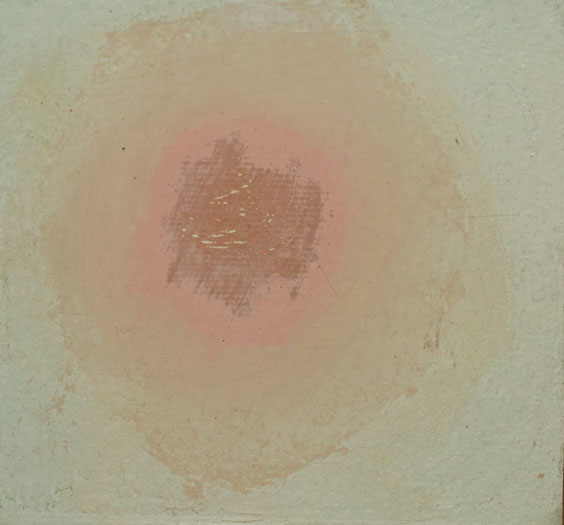

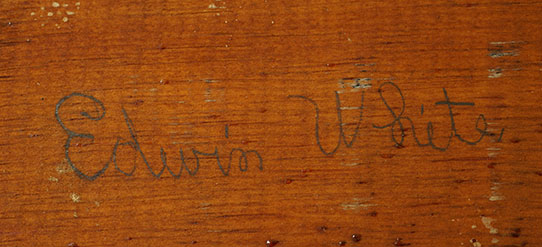

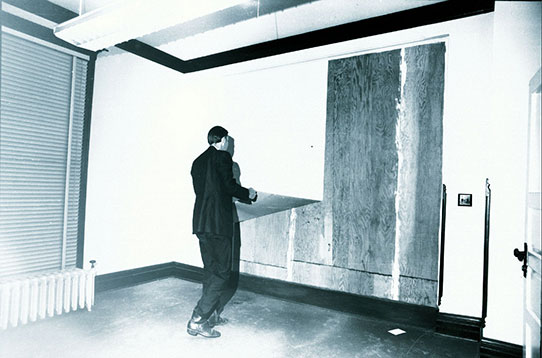

In the case of the most recent repainting by professionals in 2012 of the Former Governors’ Mansion, we did our best to match the colors to those the state initially painted the house after it was purchased in 1893. To determine what the paint looked like over the years, we carefully sanded through the layers of accumulated paint using a process known as bullseye sampling. The sampling was carried out in multiple spots protected from the elements, with samples then matched to a color swatch or taken to the paint store and matched using a spectrophotometer.

Bullseye paint sampling inside the Former Governors’ Mansion revealed the color of the upstairs hall trim from 1884 through the 1960s.

Did we get it 100% right? Since exposure to the elements can cause colors to shift on even the most protected surfaces (and the underlying and overlying paint may also alter a color’s appearance), perfection is unattainable. In this and other instances, we do our best and hope the color endures well into the future. Still, we keep in mind that inevitably best practices will evolve as understanding of historic preservation and access to new technologies increases. Imagine a world with programmable paint that could change color on demand and show the Former Governors’ Mansion across different time periods. You could see what the mansion looked like in a variety of iterations, including the 1884 maroon and green, the 1893 green and green, the 1903 yellow and maroon, or even the post-1930 white and black. Now that’s what I’d call bringing history to life!

Today computer algorithms can analyze black-and-white photographs, such as this circa 1885 Former Governors’ Mansion image, and reproduce them in color. In this instance, the computer did a good job of guessing the maroon paint color but missed the dark green trim, which it rendered in grey. SHSND SA 2005-P-006-00001

In summer 2020, Former Governors’ Mansion staff spent hundreds of hours repainting the house, which appears here in its 1893 colors.

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.