What is Historic Preservation?

Documenting, conserving, preserving, and protecting peoples’ stories are at the heart of historic preservation. Some ways to do this are through written and photographic documentation, recording oral histories, and saving historic buildings/structures and archaeological sites. Oftentimes, you will hear us refer to these things as “cultural resources.”

My job as an archaeologist exists because of a law passed by Congress in 1966 called the National Historic Preservation Act (16 USC 470). In part it reads, “The preservation of our irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so that its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans.” It created the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, State Historic Preservation Offices, the National Register of Historic Places, and the National Historic Landmark Program.

Excavation of an archaeological site.

Photo courtesy of the North Dakota SHPO

Each state has a State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). The North Dakota SHPO is located in the lower level of the Heritage Center in Bismarck. Our office serves a variety of functions, including developing and maintaining a statewide program—based on state and local needs—that supports and promotes historic preservation. This involves planning to meet challenges unique to our state; advocating for historic preservation policy at state and local levels; and empowering communities, organizations and citizens to action.

Some activities of the North Dakota SHPO:

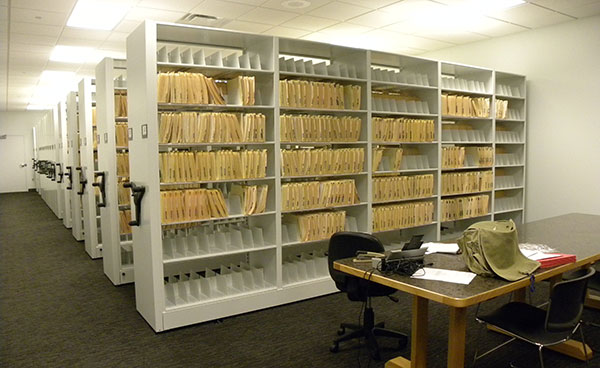

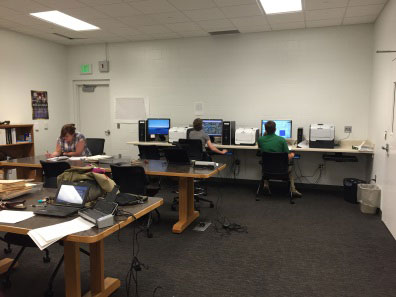

We are the repository for the documentation of recorded historical and archaeological sites in North Dakota. Part of my job is processing the paper and digital records of these sites. Currently, there are nearly 70,000 site forms on file. The SHPO staff, federal agencies, state agencies, tribal governments, and specialists utilize these records daily.

North Dakota SHPO cultural resources research room at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Photo courtesy of the North Dakota SHPO

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to consider the impact that federally funded or permitted projects will have on cultural resources. At the SHPO, we advise and assist federal agencies in this process, review project design plans, identify cultural resources, and assess and resolve determinations of adverse effect. This process gives a local voice to the federal planning and decision-making process.

The Certified Local Government (CLG) program provides for a voluntary, formal partnership between the local, state and federal governments which establishes a commitment to historic preservation. North Dakota has seven CLGs: Buffalo, Devils Lake, Dickinson, Fargo, Grand Forks, Pembina County, and Walsh County.

Income tax credits encourage private sector investment in the rehabilitation and reuse of historic buildings. The program allows the owner of a certified historic structure to receive 20% of the amount spent on qualified rehabilitation costs as a direct, federal income-tax credit. We review program applications to ensure the work complies with the Secretary of Interior’s Standards.

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) recognizes cultural resources that are considered important in the past and worthy of preservation. We write and solicit nominations to the NRHP. Listing in the NRHP puts no restriction upon a private property owner, who may alter or dispose of their property in any way they wish without any prior approvals. Listing in the NRHP does help protect cultural resources from potentially harmful federal actions.

Alan & Gail Lynch at the Lynch Knife River Flint Quarry National Historic Landmark dedication.

Photo courtesy of the North Dakota SHPO

Awareness and application of historic preservation programs enhance our community identity, increase economic development, and provide a local voice in federal undertakings. We are planning events in 2016 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act. We hope you will join us.

See preservation50.org for events across the United States.

Guest Blogger: Amy Bleier

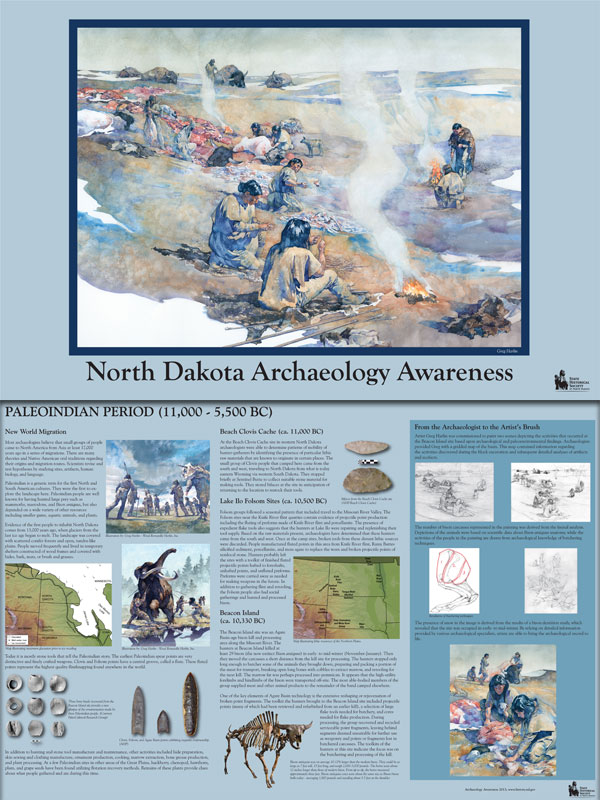

Amy Bleier is a Research Archaeologist in the Archaeology and Historic Preservation Division. One of Amy’s tasks is to assist with the production of the North Dakota Archaeology Awareness poster.

Amy Bleier is a Research Archaeologist in the Archaeology and Historic Preservation Division. One of Amy’s tasks is to assist with the production of the North Dakota Archaeology Awareness poster.