Never Stop Learning

When I completed my bachelor’s degree many decades ago, I thought that I was done with school, finished with learning. Whether that was the result of book fatigue or just the glossy idiocy of youth, I am not sure. However, I eventually returned to school and was pretty darn close to 50 when I finally received my Ph.D. in American History. This time, I did not even pause in the learning process but kept on thinking, reading, and writing history – a student with no homework.

I became very comfortable in the study of history and never suspected that I would someday hop back onto that steep learning curve to write a book in an entirely different field of study. Archaeology. I think I took one archaeology course in college (it was required), but I don’t remember much about it.

Now I am writing a book (available next fall) about the people who lived in North Dakota in ancient times. I mean really ancient times. The first people (that we know of) came here around 13,000 years ago. My training as a historian little prepared me to write about people who did not document their lives and beliefs on paper. Throughout this process, I have ranted about archaeologists’ fuzzy dates, my frustration with the limits of archaeological research (they have to go find stuff buried underground!), and their scholarly disagreements. Nevertheless, through study I have actually come to know quite a bit about North Dakota’s earliest peoples.

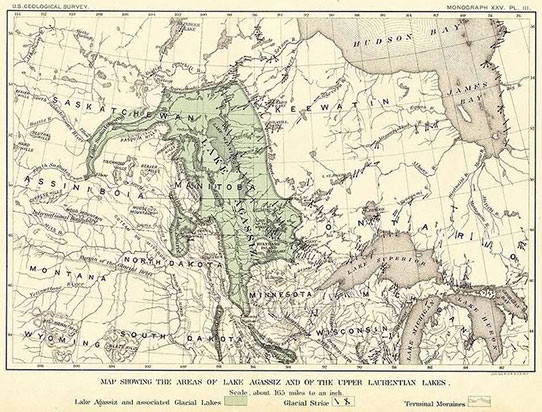

I find them likable, these people who braved North Dakota before Lake Agassiz had become the Red River, and who probably met some pretty unfriendly animals when they first looked around the northern Great Plains. The first arrivals needed to find resources quickly. They needed food – meat and berries or wild greens – and potable water. They required materials to construct shelter. They had to locate good quality stone to make into projectile points, knives, hide scrapers, and other useful items for their tool kits. These resourceful, hardworking people (like so many who followed them), found all of these things in abundance and returned again and again when they needed what North Dakota had to offer.

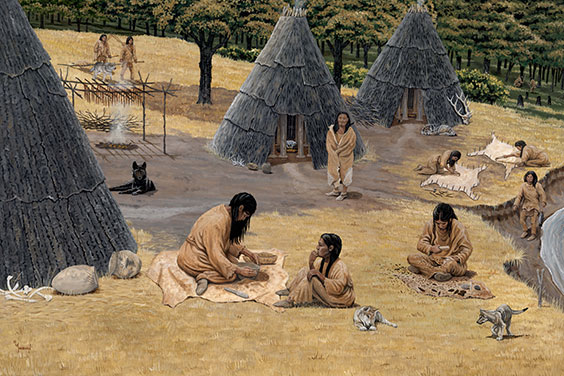

Around 500 BC, hardworking people organized villages near the resources they needed to raise their families in North Dakota. (Andrew Knutson, artist)

I have learned a lot from them. No, I can’t knap stone into a useful tool or to turn a bison hide into clothing, though there are people who enjoy doing that sort of thing. My lessons are quieter, more internal, like: Be curious. Eat new foods. Learn new skills. Adapt to the environment. Meet new people and try out new ideas. Don’t settle for what is right in front of you; something better is just over the horizon. Listen to the younger generation; they may have the right answer to the problems you face. And don’t stand still; a short-faced bear may find you delicious!