The North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum “By the Numbers”

Life as a volunteer for SHSND is always exciting and challenging. There is always a new project, a new event, or a new group of people to introduce to the many wonders of the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum.

I recently had the great fun of hosting a tour of 40 high school juniors, seniors and faculty from a Minot, ND, high school. The group was trying to pack as much as possible into their road trip to Bismarck. They visited the legislature in the morning and wanted a tour of the Heritage Center before heading back to Minot for a basketball tournament. As a result of their busy itinerary, the time allotted for their tour was short.

My challenge was to share as much information about the Heritage Center as possible in addition to allowing time for a hurried walk-through of the galleries. I decided that the only way to introduce the many distinct areas of the facility was to create and present a “photo tour” of the building.

I started the photo tour with a slide containing the following “teaser” numbers:

52 million

255,000

600 million

12 million

1

I spent the next 30 minutes revealing the meaning of each individual number.

In November of 2014, the newly expanded and renovated $52 million addition to the Heritage Center was formally introduced to the public.

On that day, 97,000 square feet of space was officially added to the Heritage Center to total 255,000 square feet under one roof. To visualize that number, we did some quick math with an example everyone could relate to. Two hundred and fifty-five thousand (255,000) square feet is equivalent to just under 5 1/2 football fields under one roof. As I explained, there is an entire unseen world one floor down from the main galleries that contributes 48,500 square feet to the total.

The challenge for a 1 hour tour was not only in roaming over 5 1/2 football fields, but also the fact that 600 million years of history are on display in the three main galleries.

It became apparent to the students that the only way to get some understanding of the many departments (called “Divisions”) and hidden corners of the Heritage Center in one hour was through the remainder of the photo tour.

In the comfort of the new Great Plains Theater, my photos allowed them to descend to the lower, secured area of the Heritage Center. As I explained to them, the lower floor is the “heart and brain” of the facility. It is here that all the artifacts and objects, as well as the information accompanying them, are prepared for display in the main floor museum galleries.

I spend a lot of my volunteer time in the Archaeology & Historic Preservation division, so I had more facts available for this area of the Heritage Center.

The Archaeology Collections Manager is responsible for 12 million artifacts in this Division alone. At any one time, about 800 of the 12 million artifacts are on display in the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples. The artifacts in the collections storage area are arranged on 20,000 linear feet of shelves—that is 3.8 miles of shelving! These artifacts represent 13,000 years of human history in what is now North Dakota.

I quickly reviewed the remainder of the lower level consisting of the paleontology lab, the archaeology lab, museum preparation lab, other collection storage areas, the Communications & Education division, museum, security, and staff offices.

From the lower level, photos moved them back to the main floor with a “stop” at the Archives Division with its 30,000 square feet of space. From there, we quickly moved on to the overall organization of the main galleries before our time was up.

I didn’t have time to tell them that we now have 300 percent more Paleoindian artifacts on display, that our annual visitation has more than doubled since we reopened, that another of our volunteers has taken 30,000 digital photos in the past 16 months, or that in addition to our 90+ paid staff, we have 200 volunteers that keep the State Museum and our state historic sites ticking.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a personal visit must be worth at least a thousand pictures. We hope to see you at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum. Please allow more than one hour to see everything!

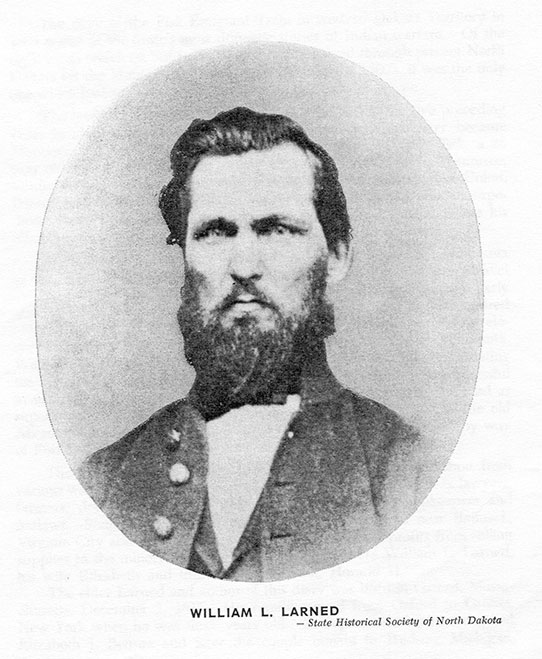

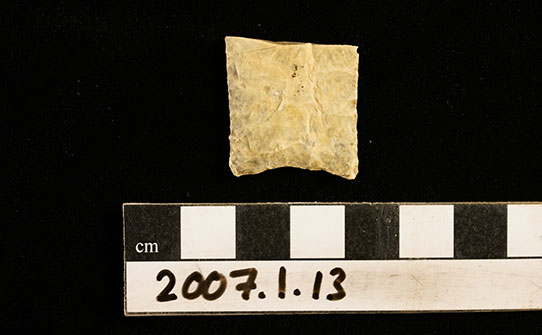

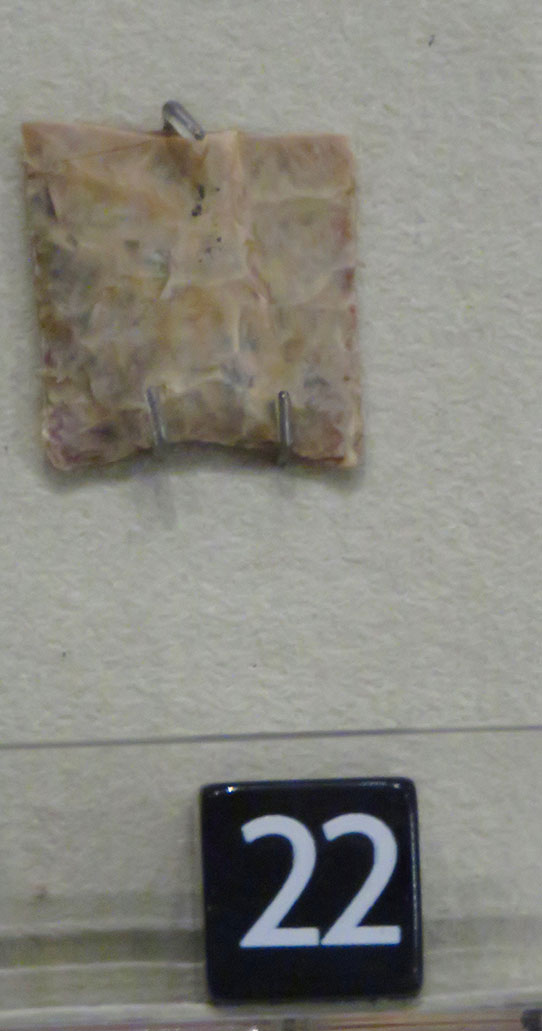

Since the discovery of number “22,” I have had the opportunity to volunteer on a number of North Dakota archaeological projects and serve as president of the North Dakota Archaeological Association. Each project is unique and brings to light a variety of interesting artifacts, each with its own story. None, though, hold the personal fascination for me that little number “22” holds.

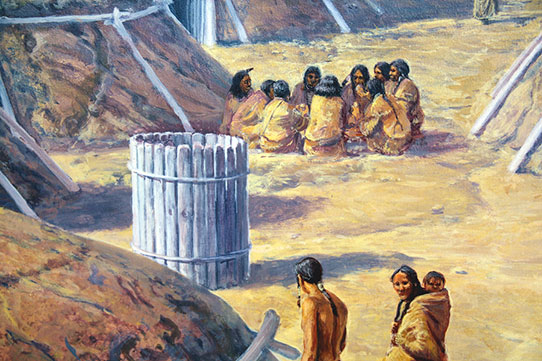

Since the discovery of number “22,” I have had the opportunity to volunteer on a number of North Dakota archaeological projects and serve as president of the North Dakota Archaeological Association. Each project is unique and brings to light a variety of interesting artifacts, each with its own story. None, though, hold the personal fascination for me that little number “22” holds. The hand-painted mural, crafted one small brushstroke at a time, shows one time in the life of the Mandan Indians. The date chosen was September of AD 1550. That very specific date was chosen by the concept team for a variety of reasons. Autumn would have been a bustling time in the thriving community, with the fall harvest and preparations for winter in full swing. The year AD 1550 would be historically accurate for the depiction of both the recognizable round earthlodge home of the Mandans in addition to its lesser known predecessor, the long, rectangular dwelling. The myriad of activities depicted include gardening, arrow-making, lodge and palisade repair, children playing, pottery making, and the preparation of corn, squash, and meat for winter storage.

The hand-painted mural, crafted one small brushstroke at a time, shows one time in the life of the Mandan Indians. The date chosen was September of AD 1550. That very specific date was chosen by the concept team for a variety of reasons. Autumn would have been a bustling time in the thriving community, with the fall harvest and preparations for winter in full swing. The year AD 1550 would be historically accurate for the depiction of both the recognizable round earthlodge home of the Mandans in addition to its lesser known predecessor, the long, rectangular dwelling. The myriad of activities depicted include gardening, arrow-making, lodge and palisade repair, children playing, pottery making, and the preparation of corn, squash, and meat for winter storage.