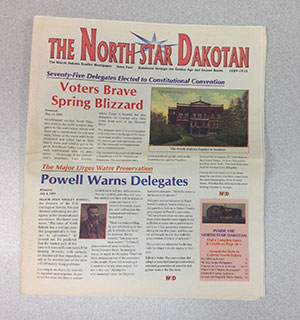

Adventures in Archaeology Collections: Larson Village

Larson Village (32BL9) is an ancestral Mandan village site that was occupied from the late 1400s to the late 1700s. In 2010 repairs were made to a modern road that runs through the site. Archaeologists excavated the area affected by the roadwork. The excavated area mostly contained cache pits (storage pits) and a midden area (trash heap)—both types of features are valuable sources of information about how people used to live! And a lot of information usually means a lot of work . . .

The collections from the excavation came to the State Historical Society’s Archaeology and Historic Preservation division in 2011. Since that time, our dedicated volunteers have been busy sorting the artifacts from Larson Village. After that much work, it is understandable that a person might wonder if any of the objects being sorted will ever be seen again! In this case, the answer is definitely yes. Part of a reconstructed pot can already be seen on display at the State Museum in the pottery case in the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples.

Reconstructed pottery from Larson Village, now on display in the Innovation Gallery of the State Museum (2012A.13.1)

However, most of the excavated items are still being sorted into different types of materials – animal bone, stone tools, seeds, charcoal, ash, pottery and more! But this does not mean that these objects will not be used or seen. The sorting is being done so that the objects can be sent to specialists who study specific types of artifacts. A faunal specialist (someone who studies animal bones) will be able to tell us more about the different types of animals that were used by the people living at Larson. Someone who specializes in lithic tools (stone tools) might be able to tell us where people found the materials that were used to make the tools, or from where the materials might have been traded. Knowing what kind of seeds are present at the site might tell us what kind of plants were being used for food, materials, or were growing in the surrounding environment. This kind of detailed information helps give us a better picture of how people lived and interacted with the world around them. After the objects are analyzed and the data is compiled, a final report can be written about the excavation of the site.

It might be a while before this project is completed, but here is a chance to see some of the artifacts found so far.

Just in time for fishing, here are some of the bone fishhooks.

Bone fish hooks and fish hook fragments from Larson Village (2012A.13)

And to give the fishhooks a better story, here are some of the many fish scales that our volunteers have also found.

Fish scales from Larson Village (2012A.13)

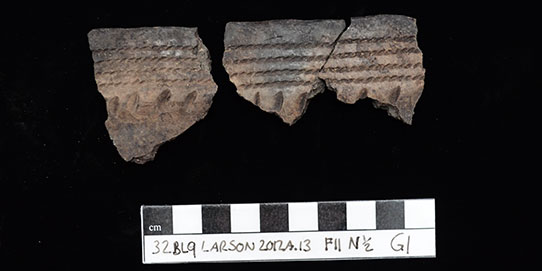

There are some very nice pottery like fragments, like the ones from this pot that was decorated with cord impressions.

Pottery decorated with cord impressions from Larson Village (2012A.13)

Pottery sherds are interesting to look at and fun to discover, especially when the fragments fit together like a puzzle.

Pottery from Larson Village (2012A.13)

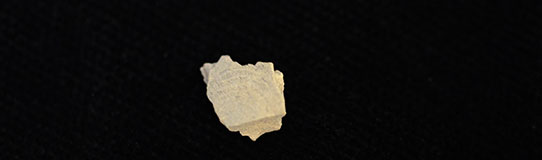

Some of my favorite things to find are fingerprints! Someone left their fingerprint impressed in the clay when they made this piece of pottery a long time ago.

Pottery fragment with a fingerprint impression from Larson Village (2012A.13)

Stone abraders are tools that were used for sharpening and shaping other tools and objects – for instance . . .

Stone abraders from Larson Village (2012A.13)

. . . all the awls! Bone awls were tools used for various things including punching holes in materials like hides for sewing.

Bone awls from Larson Village (2012A.13)

Hopefully I will be able to post more photos of artifacts from Larson Village as the sorting continues.

Projectile points from Larson Village (2012A.13)

Feel free to send me a message if you would like more information about how you can help us out in the archaeology lab.