5 Inspirational Women from North Dakota’s Past

There’s an old cliché that “history is written by the winners,” and it’s an uncomfortable fact that the winners — culturally, socially, and economically — have mostly been men. The result is a historical narrative biased toward men’s deeds with an often deafening silence surrounding women’s accomplishments. Women, however, have always been a part of making history. In recent years women’s stories have come to light and are adding to, if not rewriting, part of our shared history. Here are just a few remarkable women from North Dakota’s past.

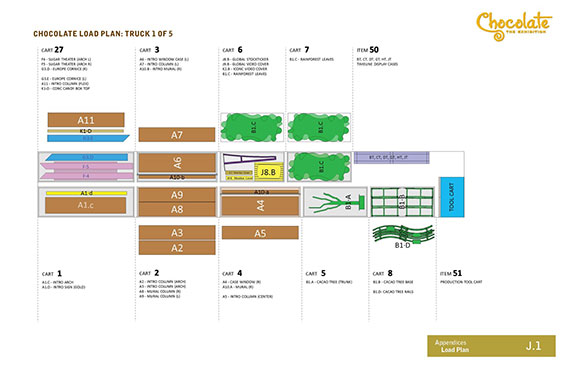

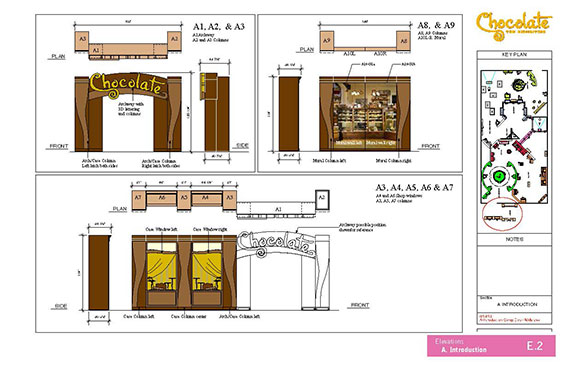

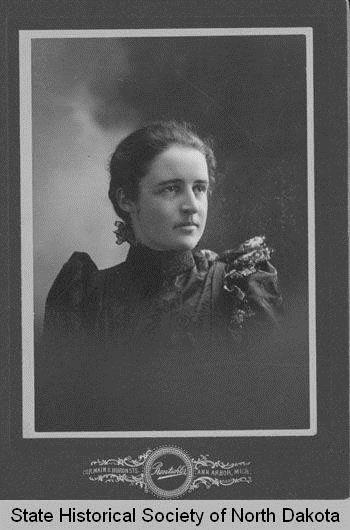

SHSND 00091-0252

Dr. Fannie Dunn Quain

Dr. Fannie Dunn Quain (1874–1950) was North Dakota’s first licensed female physician. As a young woman, she worked multiple jobs to save money to go to medical school. She graduated from the University of Michigan in 1898 with a doctor of medicine degree. After moving to Bismarck, she became a prominent figure in the area and was elected Burleigh County’s superintendent of schools. She had an active private medical practice for many years, but later turned her efforts to organizing the North Dakota Tuberculosis Association.

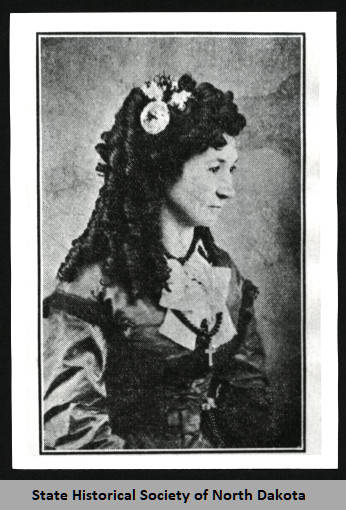

SHSND 10003-0009

Linda Slaughter

Linda Warfel Slaughter (1843–1911) accompanied her husband, a military surgeon, to Fort Rice in 1870 (http://blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/linda-warfel-slaughter-bismarck-pio…). After moving to Fort Hancock, near Bismarck, she effectively filled the role of postmaster, although technically her husband held the position. She was a prolific newspaper columnist, Bismarck’s first teacher, Burleigh County’s first superintendent of schools, a leading figure in the woman suffrage movement and an organizer of the Ladies Historical Society, which later became today’s State Historical Society of North Dakota.

NDSU 2094.2.1

Minnie Craig

In 1923 Minnie Davenport Craig (1883–1966) was elected to the North Dakota House of Representatives. Ten years later she became the first woman speaker of a state House of Representatives in the nation. She ultimately served six terms in the North Dakota legislature and was a Republican National Committeewoman for North Dakota from 1928–1932.

Minnesota Historical Society

Florence “Tree Tops” Klingensmith

Florence Anderson Klingensmith (1904–1933) had an insatiable appetite for speed. Inspired by Charles Lindbergh, Klingensmith learned to fly, earning the nickname “Tree Tops” when she became North Dakota’s first female licensed pilot. She persuaded local Fargo businessmen to donate money for a plane in exchange for free advertising space on it. She bought a Monocoupe named Miss Fargo in 1929. Now licensed and with her own plane, she set out to break flying records. In 1931, over four hours, she completed 1,078 loop-de-loops, an average of four loops per minute. She did exhibition flying, and won international air races against men and women. In 1933 she tragically lost her life during a race in Chicago when a faulty wing caused her plane to crash.

SHSND D0566-1

Scattered Corn

Scattered Corn (1858–1940) was a respected Mandan seed keeper and daughter of the last corn priest, Moves Slowly. With no successors, his medicine bundle came to Scattered Corn, who did her best to continue the traditions and maintain the accumulated wisdom of generations. Over hundreds of years, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara gardeners had developed vegetable varieties appropriate for northern climates. Scattered Corn shared her knowledge about native agriculture and Mandan traditions. Seedman Oscar Will began selling corn seeds originally sourced through Scattered Corn in his seed catalog. Ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore recorded Scattered Corn singing ancient prayer songs. Because of Scattered Corn’s generosity, many aspects of Mandan agricultural traditions have been preserved for future generations.