The Art of Making Fossil Casts

A few blogs ago, I introduced the good kind of mold we have in paleontology: silicone rubber, used when making casts of fossils. Depending on the purpose of making a cast, the end result can look very different. If we need to make a cast to replace an original fossil, a lot of time and care are taken to paint the cast to make it look as close to the original as possible. If a cast is meant to be a teaching tool, handled frequently, or given away as a prize, then maybe a more generic paint job (i.e. less time) is used.

There are times when people are conflicted – they found a cool fossil, and they want to donate it to the State Fossil Collection, but they would also like to keep it to show their friends and family. Depending on the fossil, we can make a cast and paint it to match the original. This way the person can keep what looks (and even weighs) the same as the original, but the real one is safe in collections.

Two painted casts of a mosasaur vertebra, and the original. Which is which?

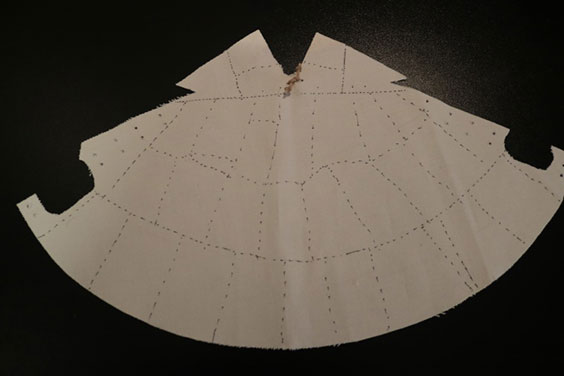

During our 2017 dig season, our public diggers came across two beautiful Tyrannosaurus teeth. Everyone wanted the teeth – yet there is only one of each. What to do? Make copies and paint as close to the original as possible. After making a silicone mold, it was time for an assembly line. There is no point to mixing up all the paint you need, over and over, to paint one tooth at a time. So we cast a bunch, mixed our paint, and started the lengthy process. In order to keep all the surface texture, the paint had to be applied in thin layers. Wash after wash. While it is nearly impossible to match a tooth exactly, we can get close enough. This means lots of small brushes, and patience.

One of the failings of casts is that they are often much lighter than their rock counterparts. To fix this we weighed the original tooth (171 grams). When mixing our plastic (~65 grams), we made up the difference in weight by adding metal BBs without adding a lot of volume.

Original Tyrannosaurus tooth (left) and 80 percent painted cast (right). Weight distribution in both teeth is the same.

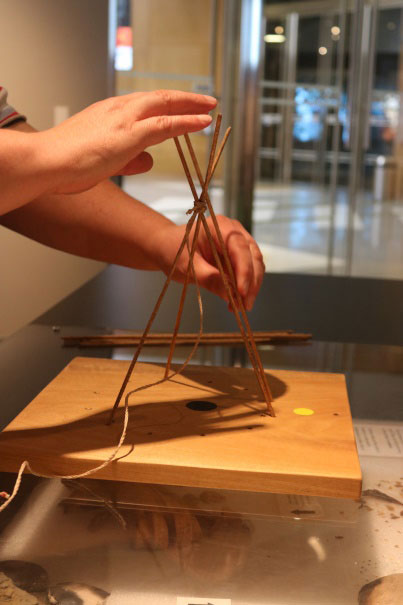

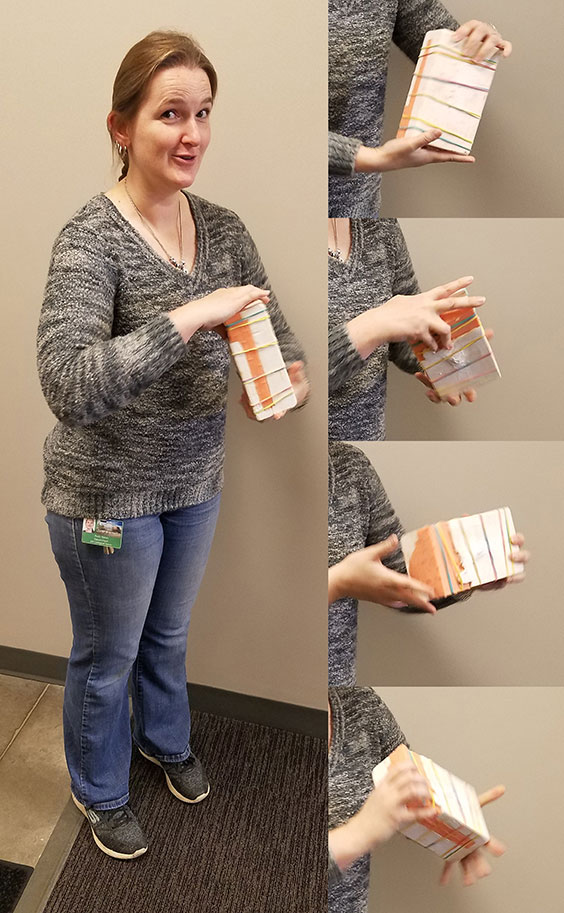

We can’t just let the plastic and BBs sit in the mold, or all of the weight would be on one side. So, we have to rotate the mold until our plastic sets. Time consuming? Yes. Great arm workout? Yes. Awesome teeth? Totally.

Becky becoming the human gyroscope. Turn, turn, rotate, pivot.