An Archives Christmas

As we are in the midst of the holiday season, the sights turn to snow, lit up houses, Christmas trees, and packed shopping malls. Our thoughts turn to time with family and friends, holiday parties, and gift giving. Often, this time is one that we reflect on past seasons and special gifts that brightened our childhoods and memories that will last a lifetime and beyond.

The vast collections of the State Archives provide many treasures and resources for understanding life in days gone by. It seems appropriate to consider items and collections that allow casual visitors and researchers opportunities to learn about how people in our area experienced the holiday season. We have a number of resources available related to the Christmas season that will generate curiosity and personal reflection.

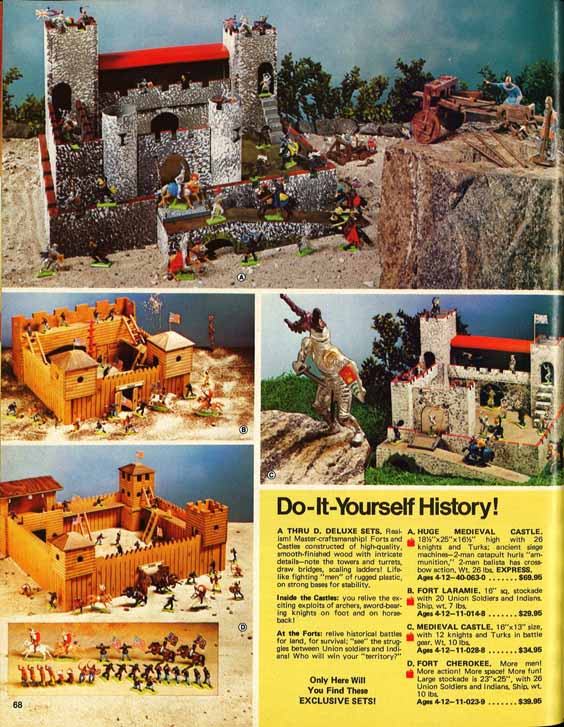

Have you ever wondered what items your parents or grandparents may have had on their wish lists? Curious as to what items were available for possible gifts during Christmases past? We have catalogs from JC Penney, Montgomery Ward, and Sears that span several years. This is something many may remember doing as kids, circling the toys and other items we hoped would be waiting for us under the tree Christmas morning. These catalogs are wonderful resources to the material culture of preceding generations, illustrate changes in fashion, and provide insights into the economic history of our country. We also have an FAO Schwarz toy catalog for the fall and winter season of 1974-1975 that is full of unique toys, including the ones on the page image below.

One page featuring some history playsets in the 1974-1975 FAO Schwarz Fall & Winter catalog.

In addition to looking at our assortment of store catalogs, those curious as to what potential gifts made Christmas lists in past decades can also examine our extensive newspaper collection on microfilm. Advertisements for goods were a common sight in North Dakota newspapers. While our minds usually gravitate towards grocery items when considering such ads, other local businesses ran ads in the pages of their local paper announcing deals on clothes, toys, televisions, and many other items. Our newspapers are also a great resource for seeing what the communities in North Dakota did around the holidays in terms of events.

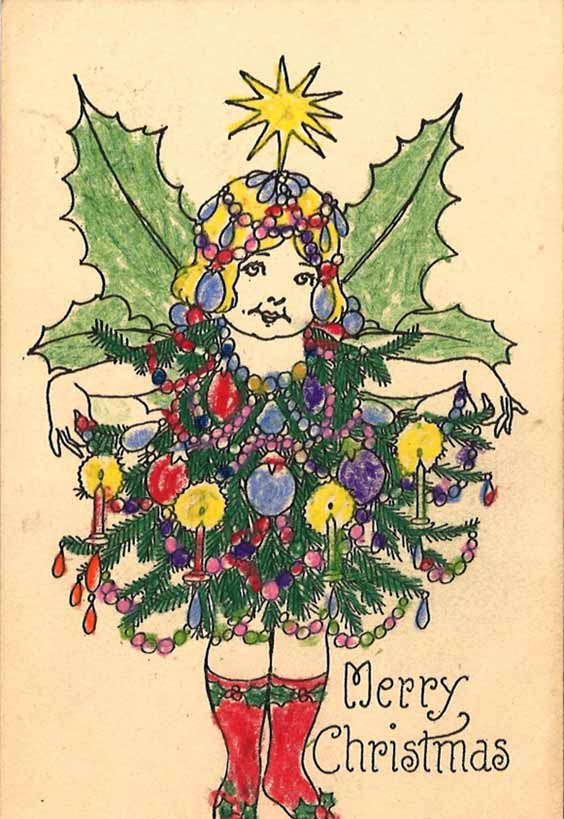

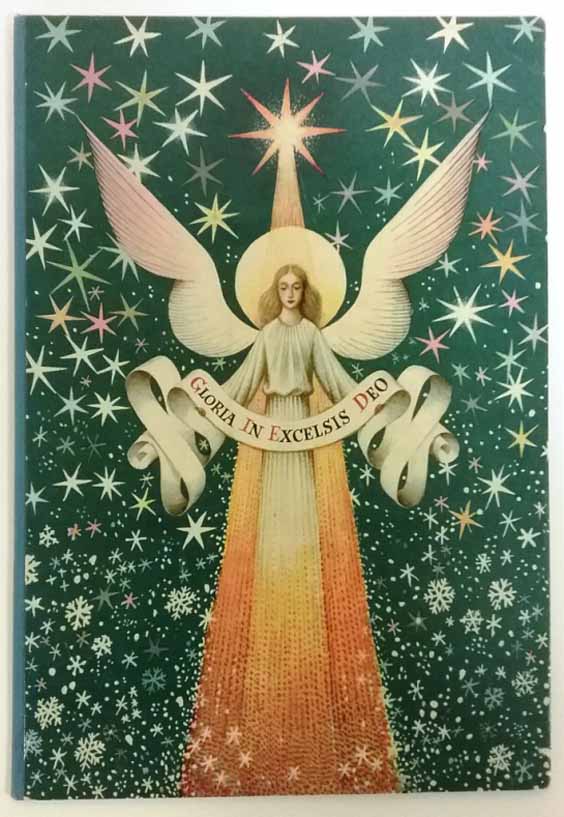

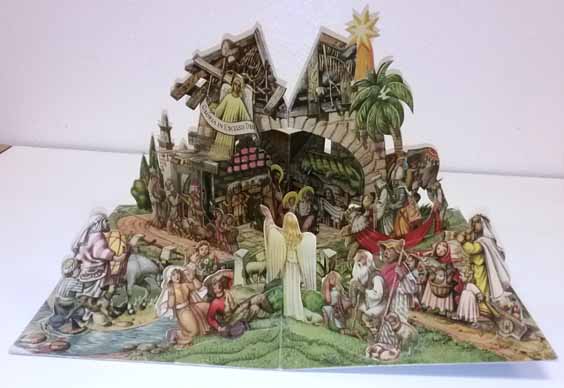

Greeting cards, whether homemade or store bought, are a common item associated with the Christmas season. Several of our collections contain examples of such cards and range from simple to very ornate. The Martin M. Stasney Papers (Series# 10630) contains an example of a child’s card, as Violette Stasney colored a Christmas postcard in crayon. Another example of a Christmas card comes from the Della (Moos) Schoepp Papers (Series# 11080) and is a large Christmas card that opens to a detailed pop-up Nativity scene.

Christmas postcard colored in by Violette Stasney, part of the Martin M. Stasney Papers (Series# 10630).

Front of Christmas card from the Della (Moos) Schoepp Papers (Series# 11080). Photo by Daniel Sauerwein.

Inside of Christmas card from the Della (Moos) Schoepp Papers (Series# 11080). Photo by Daniel Sauerwein.

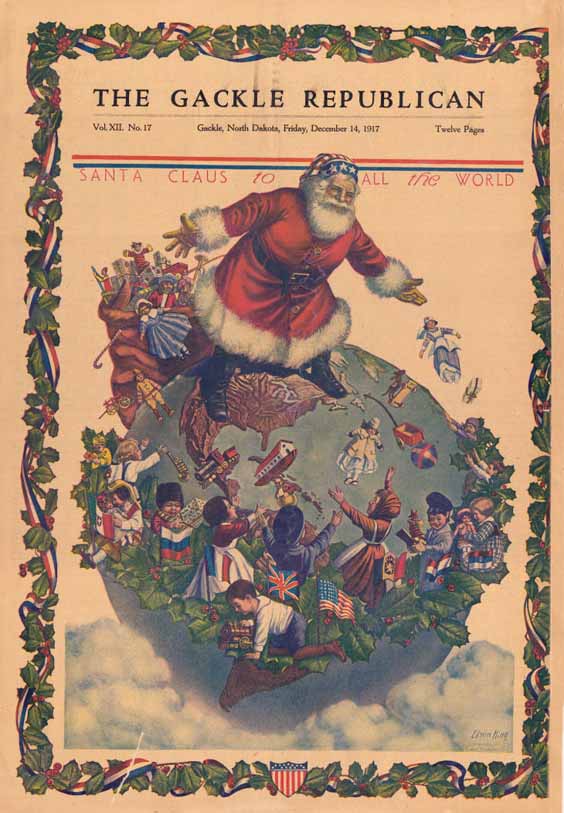

Our holdings on Digital Horizons also provide some interesting Christmas related items. One example is from World War I, when the Gackle Republican ran an image on the front page of its December 14, 1917 issue featuring Santa Claus standing upon the world, passing out gifts to various children of the world, under the caption, “Santa Claus to all the world.” It is interesting to note that only the children of Allied nations are represented, clearly denoting that America is at war and that the enemy’s children are deemed not deserving of gifts at Christmas. This prime example of wartime propaganda during the Christmas season conveys the efforts to dehumanize citizens of the enemy nations and stands in stark contrast to the meaning of the season. The image also symbolizes that there were men fighting in the trenches during the season as well who were away from loved ones.

Front page of the December 14, 1917 issue of The Gackle Republican, featuring Santa Claus passing out gifts to the Allied children of the world.

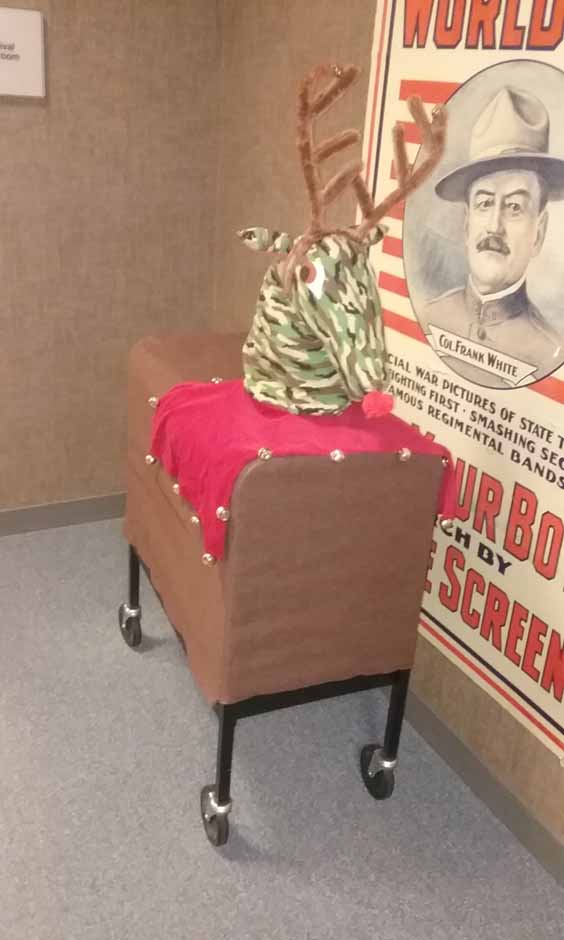

Finally, while there is a lot of work that goes on in the Archives, we also make time to get in the holiday spirit by doing a little decorating and bringing out a staff favorite. This is my first Christmas with the State Historical Society. I was introduced to a tradition in the Archives of bringing out Olive, the other reindeer, who I have been told by fellow Reference Specialist Sarah Walker is a boy, was the creation of our State Archivist, Ann Jenks, and stands watch by the reference desk. He’s quite the character to say the least. Who says archivists can’t have a little fun?

Olive sends holiday greetings from the Archives. Photo by Daniel Sauerwein

I hope as you prepare your own activities for the holidays, you take some time to stop by and look at the treasures of Christmas past we have in our collections. We wish you a safe and happy holiday season.