Occasionally as part of my duties, I give tours of collection storage to members of the public. We have a collection of 70,000 artifacts, 90% of which are in storage at any given time. When people see how many artifacts we have in storage, many ask, “What’s the point of having all of these things if you don’t put them in an exhibit?” I am so happy when they ask, because it gives me a chance to share what drives me to do what I do and what makes me passionate about my field.

So why do we have all that stuff back in storage? We work to create an official historical record for our state and our region, a body of objects that encapsulates what life was like in North Dakota in the past and what it is like in modern times. In the same way that an archives collects government records or personal letters, we collect the three-dimensional artifacts that make up our everyday life and that preserve stories from our past. We work hard to ensure that North Dakota’s story is around for centuries to come. I wanted to show you some of my favorite items from the collection that reflect the breadth of the stories we collect and preserve.

We do collect items from significant events in North Dakota history, whether it’s a battle, a change in government, or a natural disaster. You will find items such as sandbags from flooding in Fargo, voting machines, and suffragette banners, just to name a few. One of those significant events associated with North Dakota history is the Battle of Little Bighorn.

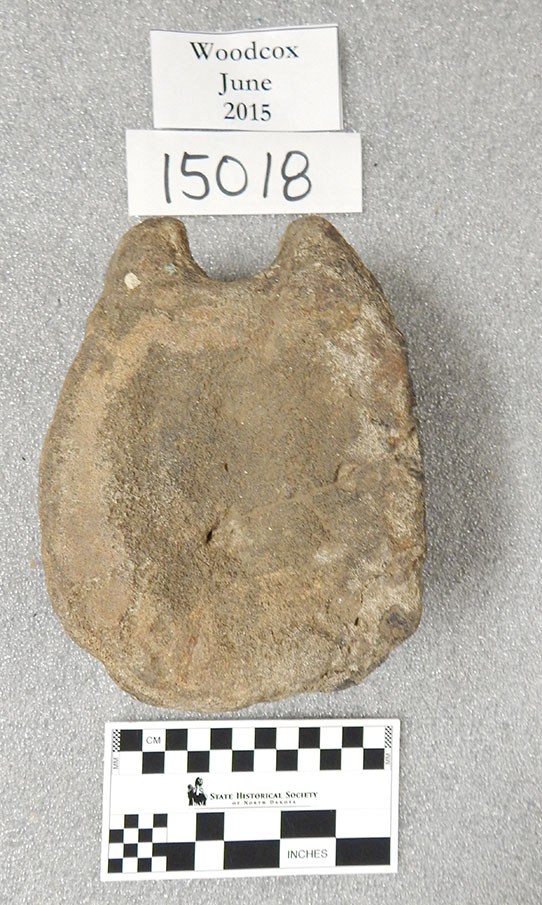

The battle occurred in southeastern Montana in July 1876, but Custer and his men departed Fort Abraham Lincoln south of Mandan, North Dakota, two months prior. There are many items in our collection associated with the battle, two of which you can see below.

Pictured here is a lead bullet and empty cartridge that were possibly dug up from the battlefield of the Battle of Little Bighorn. Custer’s men carried the “trapdoor” Springfield .45-70 carbine, which was the first standard issue rifle of the US Army that was not a muzzleloader or musket.

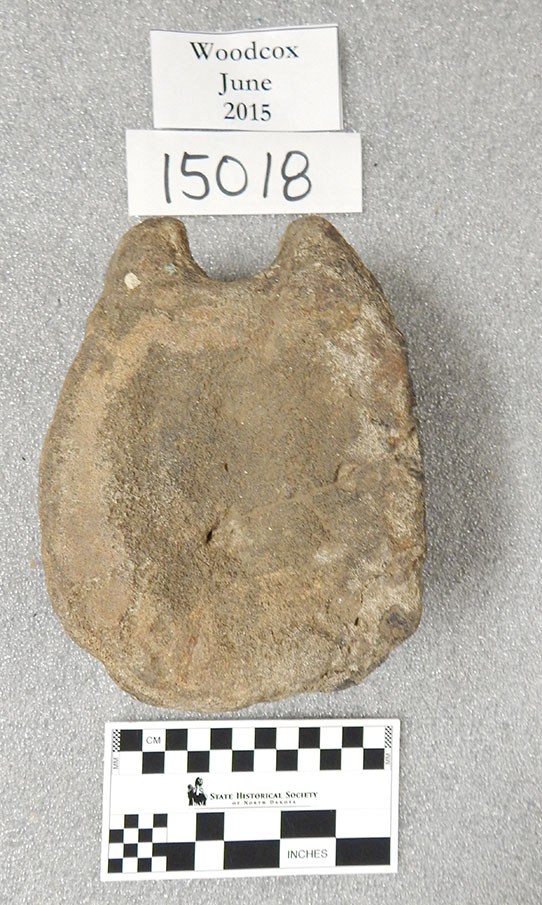

According to our records, this is the vertebrae of a triceratops. It was found in Emmons County in south-central North Dakota.

Today, the State Historical Society partners with the North Dakota Geological Survey to create places such as the Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time in the North Dakota Heritage Center’s State Museum, and the NDGS is the caretaker of the state fossil collection. Before this partnership, the State Historical Society acquired and maintained a large collection of fossils from around the state. Below, you can see one of the fossils in our collection, which we acquired in 1943. Though the Historical Society no longer actively acquires fossils, they make up a moderate, though in my opinion, very cool part of our collection.

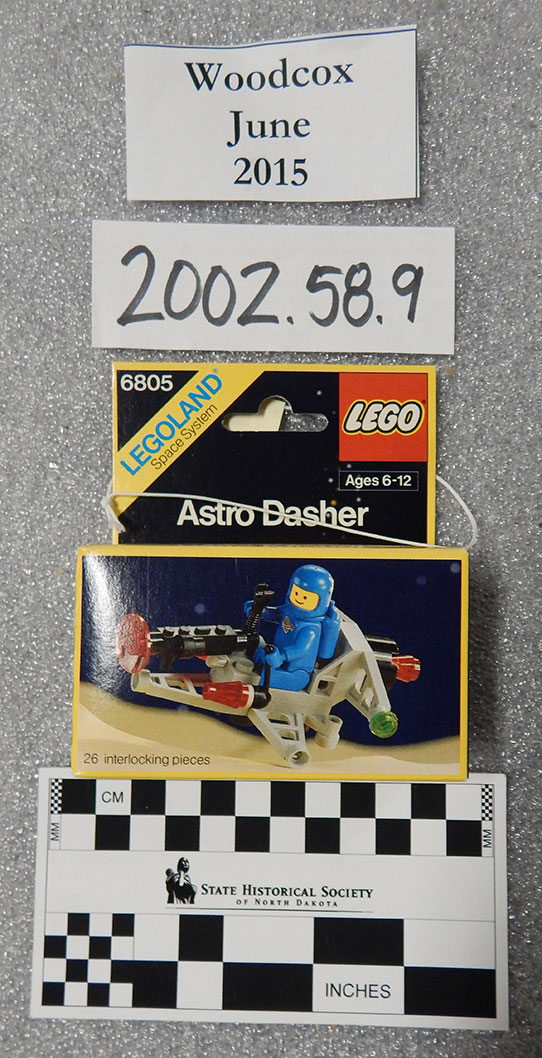

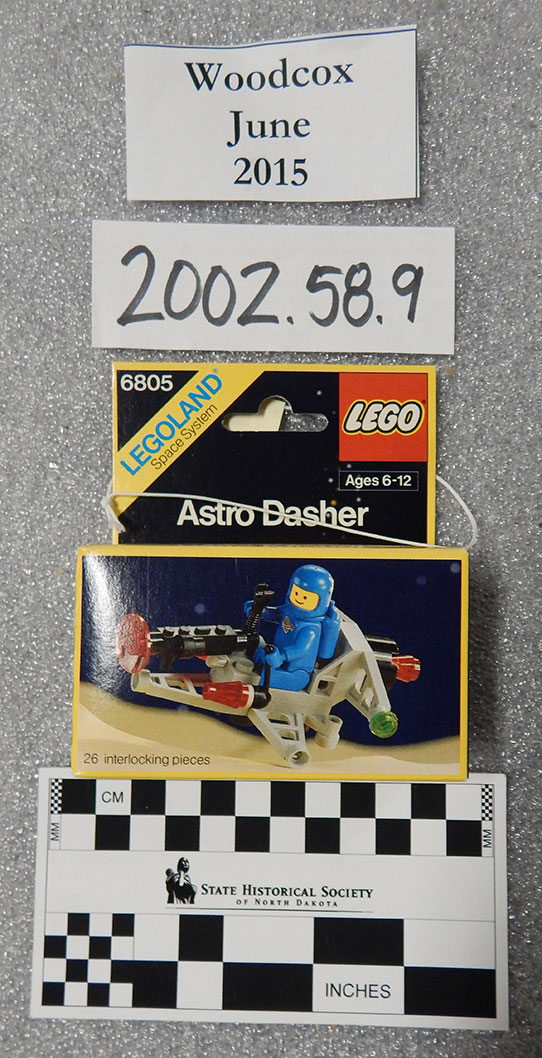

Released in 1985, this classic Lego set is one that may be familiar to many kids of the ’80s and ’90s.

We also collect items from people’s everyday lives. Clothing, toys, games, food packaging—all of these things make up the fabric of our lives today, and it’s an important story to preserve in the historical record. As a child of the ’80s and ’90s, one of these everyday items that speaks to me in particular is a Lego set. As a kid, I spent countless hours playing with Legos, and it’s a common story for children of the last 40-50 years. It’s important to preserve this childhood story of creativity and imagination!

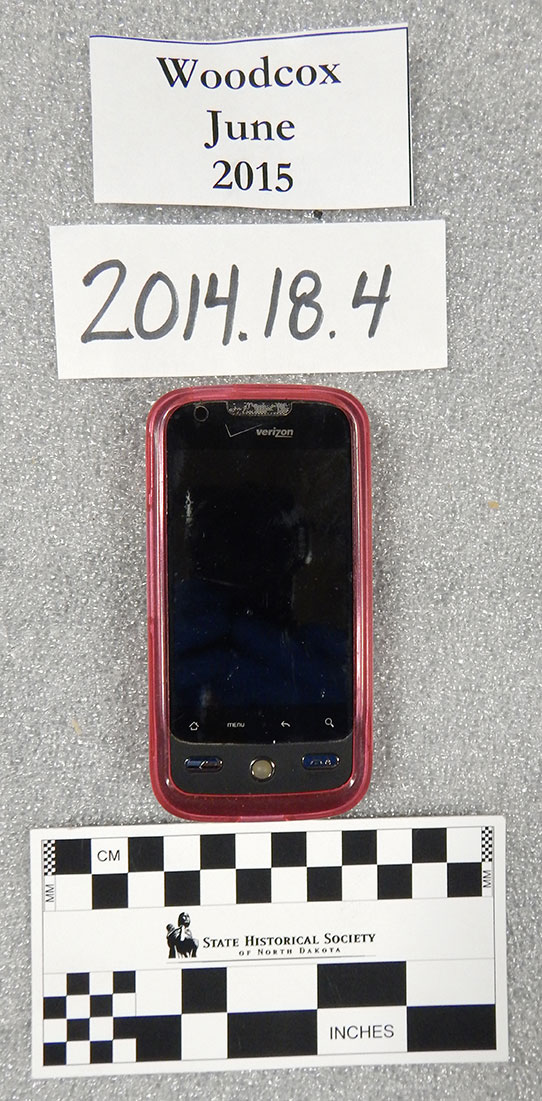

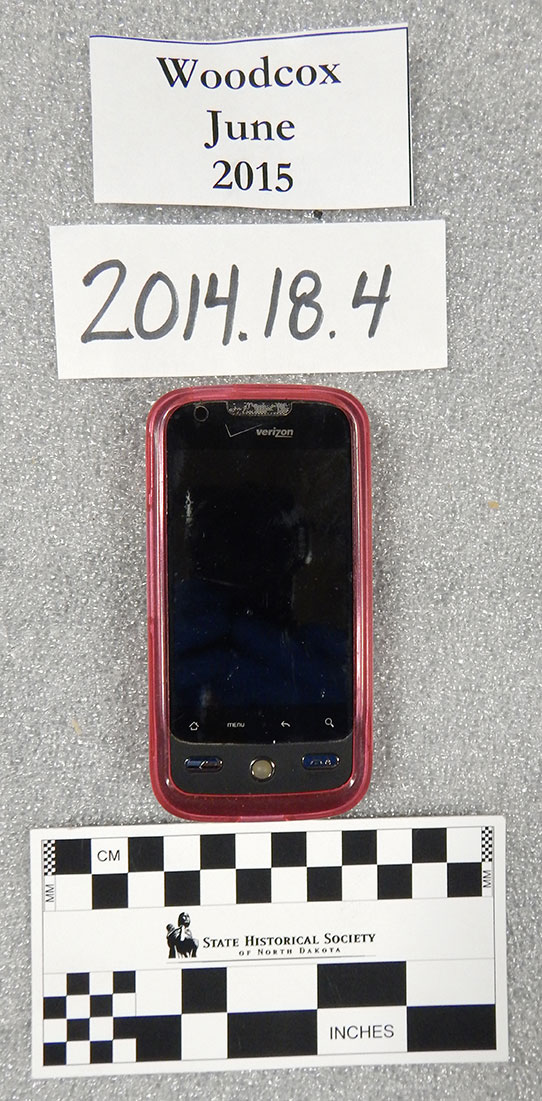

Smartphones are a huge part of 21st-century life, and it’s a piece of the story that we try to preserve. Technology such as smartphones, laptops, and digital cameras is difficult to acquire because these pieces are sometimes viewed as disposable once they’re no longer of use.

We are constantly collecting modern items, and contemporary technology is a big part of that. Purchased in 2009, this smartphone is one of many pieces of modern life that we’re trying to preserve. It’s a challenge to collect electronics because, by their nature, they’re disposable and replaceable. But how can you talk about life in the 2010s and not talk about smartphones? They’re everywhere!

I chose these four items to show you the breadth of the collection and the stories we’ve tried to preserve so far. But what stories can you add to the narrative? By donating an artifact to the State Historical Society, you not only help expand our collection, but add your voice and your story to the historical record.