Back to Your Roots: State Archives Staff-Recommended Genealogy Collections

October is American Archives month. To celebrate, we are sharing all things related to the State Archives! Our staff works very closely with our collections, which allows us to gain unique insights into these documents and materials. In this post, we highlight some of our favorite resources that we think have great value for personal history and should be utilized more by the public for genealogical research. Check out the list below, and if you have any questions along the way or are interested in accessing these treasures, don’t hesitate to reach out to our reference staff at archives@nd.gov or 701.328.2091.

Emily Kubischta, Manuscript Archivist

Yeehaw! In 1957, the 50 Years in the Saddle Club was organized in New Town by 22 cattlemen who had been ranching and working with cattle for at least 50 years. The group aimed to keep memories and tradition alive by annually gathering to reminisce, and their efforts resulted in the four-volume series “50 Years in the Saddle: Looking Back Down the Trail,” as well as a variety of biographies and stories of ranchers and other residents of western North Dakota. Although the biographies vary in terms of length and content, they are wonderful resources for genealogists and western enthusiasts alike. There is bound to be a person or topic of interest to anyone researching the Old West in North Dakota in the 50 Years in the Saddle Club Collection (MSS 11366).

Daniel Sauerwein, Reference Specialist

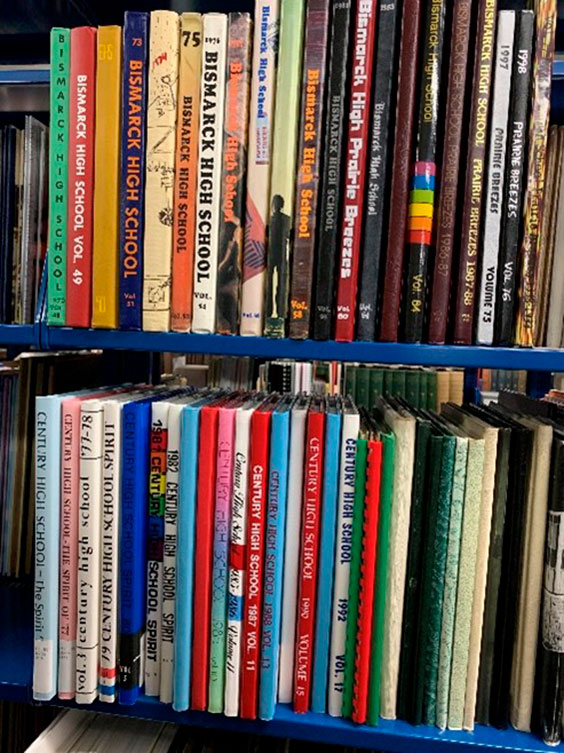

A great genealogy resource in the State Archives is our collection of yearbooks from various schools, colleges, and universities across North Dakota. While they require a little more background knowledge of your ancestors, such as knowing what school they attended, yearbooks are an exciting way to uncover photographs of ancestors from their younger days and learn what they did in school. Whether your ancestor was a star athlete or outstanding scholar, yearbooks also show familial and community ties, since by glancing at surnames you can trace your family’s trajectory through the years. We are always looking for more yearbooks to grow this resource so please consider donating your yearbooks to help preserve this history.

A selection of Bismarck High School yearbooks in the State Archives.

Ashley Thronson, Reference Specialist

A lesser-used resource at the State Archives for genealogy research is the local government collections. County court case files, including probate, civil, and criminal case files, property assessment records, and some township records are found in these collections. These records can be a little difficult to use as they are not digitized, the records are not all in one place, and the records we have for each county may vary. If you are interested in seeing what local government records we might have on your ancestor, check out the local government records pages on our website.

Virginia Bjorness, Head of Technical Services

The State Archives has nearly 1,400 family history books, many containing a treasure trove of research, stories, and pictures! Written and published by current and former North Dakotans (or relatives with ties to the state), these works can be an unexpected gem for genealogists. Some also contain valuable information about the settlement and development of places across North Dakota. Search for your family’s name here.

Lindsay Meidinger, Head of Archival Collections and Information Management

Although probably a bit of an unconventional genealogical resource, the North Dakota news film collections offer a unique glimpse at the past through a visual of the people, places, and activities that our relatives encountered during their lives. Covering nearly every corner of North Dakota and spanning the 1950s to the 2000s, the news film collections contain raw segments, complete stories, and a plethora of sports clips and games. I personally was able to find out more about my own genealogy through the WDAY-TV collection. One day while digitizing some film, I stumbled upon a segment titled “Postman Arrested and Taken to Banquet in His Honor.” My dad once told me about my great-grandfather, Thomas Cullen, who was a mailman in Fargo for 39 years and never once involved in an accident. Sure enough, the news film segment I had just digitized was footage of my great-grandfather! Through this archival news film, I learned that Fargo city officials and police officers decided to surprise him by “arresting” him and taking him to a party honoring his astounding driving record and service to the city.

Postman Thomas Cullen is "arrested" for his exemplary driving record. SHSND SA 10351-2146-00005

Sarah Walker, Head of Reference Services

We have a multitude of collections that provide solid genealogical documentation. However, our oral history collections are some of my favorite sources to use for family history research. Sometimes these oral history interviews are more focused on history than family history, and sometimes they are essentially biographies of the person or people being interviewed. No matter the focus, both history and personal history intertwine and shine through. Even if your family did not contribute an oral history themselves, their contemporaries may have. For example, I discovered in our collections an oral history of the wife of a doctor who took care of my mother’s family when she was young. That was a cool find!

Box of cassettes from the Bicentennial Oral History Collection (MSS 10157).