Interns Learn About the State Archives From the Inside Out

Colby Aderhold, Photo Archives Intern

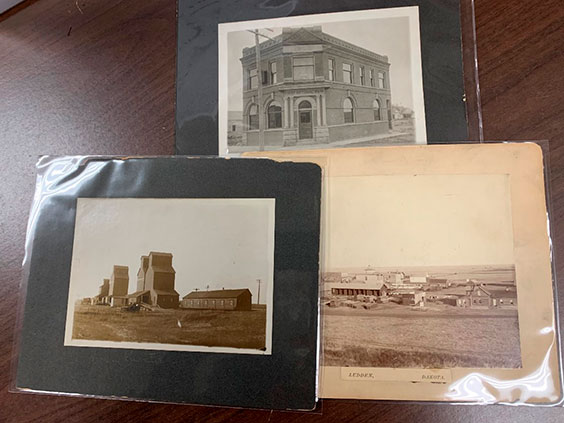

I am a senior at the University of Mary studying history, philosophy, and classics. This summer I had the privilege of working as an intern at the State Archives. My project was to inventory and organize the Reverend Harold W. Case Photograph Collection at the container level. In total, I inventoried and organized 215 boxes and 17,312 individual items. The collection contains a variety of photographs, including safety negatives, nitrate negatives, tintypes, slides, film, glass, and prints of various sizes. Each item requires different conditions for storage. A part of my job was to make sure these individual requirements were met for each photograph. Negatives were paper sleeved and placed on a shelf; tintypes were put in paper sleeves and given their own boxes. Glass was assessed for damages and scanned, then stored in special boxes on the lowest shelf to avoid accidental shattering. Slides, prints, and film were placed in paper sleeves, and every item, irrespective of type, was given a unique item number.

Throughout the project I was amazed by the Rev. Case’s skill as a photographer! Case, a New Yorker who arrived in Elbowoods in 1922 to serve the Fort Berthold Mission, would work there until much of the area was flooded by the construction of the Garrison Dam. His pictures really captured life around the mission and serve as a time machine for the interested researcher. Below is my personal favorite, which shows a massive crowd gathered to witness the 1934 dedication of the Four Bears Bridge. The image makes the viewer feel as though they are a part of the gathering.

SHSND SA 00041-05211

This internship has taught me the value of organization and the proper methods of archival research. Mistakes were sometimes my greatest teacher. If I left my desk untidy or my cart full of photographs it would result in more difficult and slow work the next day. If I procrastinated due to the difficulty of a specific task, it would only make this already challenging task even harder. I quickly learned to clean up every day before I left the office and to never leave a task halfway done promising to complete it another day. These lessons have spilled over into my daily life and have also resulted in a cleaner house and reduced stress.

Finally, I learned how to properly research sources while working within an archive. Though many aspiring historians must learn how to use an archive from the reading room, I have had the good fortune of learning the inner workings of the State Archives from behind the scenes. This has been a great advantage this summer as I have been doing archival research in the Huntington Library’s collection for my undergraduate dissertation project. Moreover, this skill will prove invaluable as I move forward in my career.

In conclusion, this has been a very successful summer internship, and I cannot wait to return to the State Archives in the capacity of a work-study student.

Connor Grenier, Local Government Archives Intern

Though my internship started in May my hiring process began in March. Graduation was rapidly approaching, and I needed to find a position that could offer me work experience related to my career goals. Back in March, this internship seemed like a promising place to start. Now that the internship is complete, I have gained valuable experience that has better informed what my interests are and where my goals are aligned for the future.

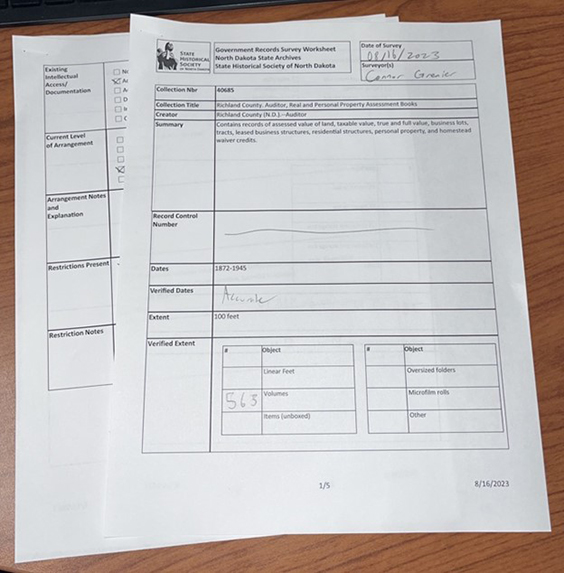

My main project at the State Historical Society was running an inventory survey for the material in the local government archives. My tasks gave me insight into archival work. It was interesting to discover the materials that an archive contains and how these are preserved and processed. The work here is never finished. I find this last point to be the most hopeful as I seek to pursue similar work. While I spent most of my time on the inventory project, I also had the opportunity to engage in other archival duties, such as digitizing audio and video material.

A collection audit form used during an inventory survey of local government archives materials.

This internship has also shown me the other career routes the state offers. Whether it was painting picnic pavilions at a state historic site, touring another department at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum, or networking with my fellow state interns, I was exposed to the different opportunities and options that this field has to offer. I gained a lot of experience from my tasks, but I learned the most from my colleagues here. Getting to know the work of the people around me was very interesting and eye-opening. I got a better sense of what this work requires and the many avenues people could take within the field. I would also like to note that the work environment at the agency is very fun and kind. Everyone here is willing to teach you something you do not know and is not afraid to have a laugh. Overall, I had a positive time in this position, and I hope that the work that I did reflects that.