Enhancing Archaeological Collections Access and Preservation With 3D Technology

3D scanning allows for the preservation of artifacts in digital form, safeguarding them against physical deterioration or damage. 3D modeling can be used to preserve digital replicas of delicate, rare, and ancient artifacts, enabling the storage and study of objects in far greater detail than traditional 2D images (Eve 2018; Garstki 2016; Graham 2012; Younan and Treadway 2015). In cases where artifacts suffer damage, the stored 3D digital model can assist in the restoration and repair of the affected parts. Conservationists can use digital models to plan and execute precise restoration work without directly handling the original, ensuring its protection (Eve 2018; Graham 2012).

The author 3D scans a pottery sherd from On-A-Slant Village near Mandan.

Digital archives can expand access to archaeological materials, with 3D scanning serving as a pivotal tool for museums to enhance the accessibility of their collections (Garstki 2016). By uploading 3D scans to websites, a virtual display can be fashioned, reaching viewers across the globe (Eve 2018; Graham 2012). This approach allows researchers, students, and the public to remotely explore collections, thereby democratizing access to knowledge. These models may enhance the research process, offering improved accessibility, detailed analysis, collaborative opportunities, and the capacity to conduct experiments. This, in turn, contributes to preservation efforts and educational initiatives. For the public, the virtual display may serve to cultivate interest and appreciation for history and cultural heritage (Garstki 2016; Montusiewicz, Barszcz, and Korga 2022; Younan and Treadway 2015).

Beyond generating models, 3D printing enables the production of tangible replicas of artifacts that can be used for educational, exhibition, and preservation purposes (Graham 2012; Montusiewicz, Barszcz, and Korga 2022). 3D printing enables the replication of rare and fragile objects suitable for hands-on activities, research, and preservation purposes. Handling physical artifacts allows for a more immersive learning experience than merely observing objects within glass display cases. These 3D-printed replicas also serve as accessible tools for individuals with visual or sensory impairments, enabling them to interact with the exhibits through touch (Montusiewicz, Barszcz, and Korga 2022). Moreover, by scanning and producing 3D replicas, museums can potentially loan out precious artifacts, preserving the originals while sharing their replicated forms (Graham 2012).

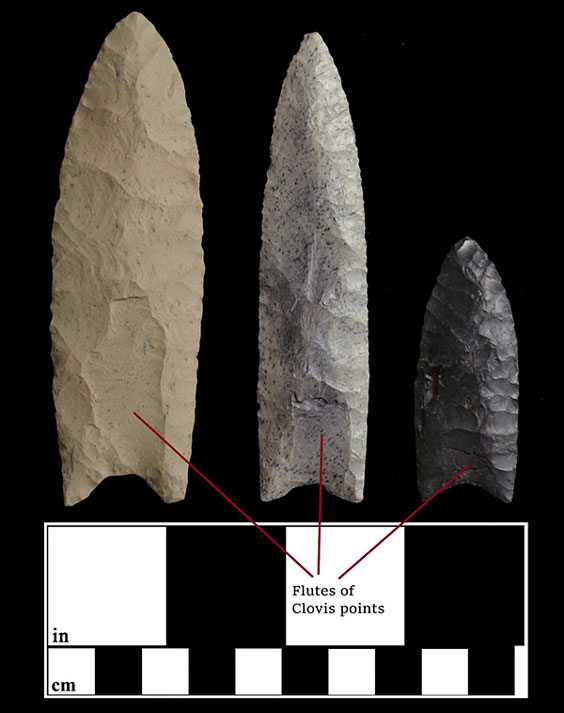

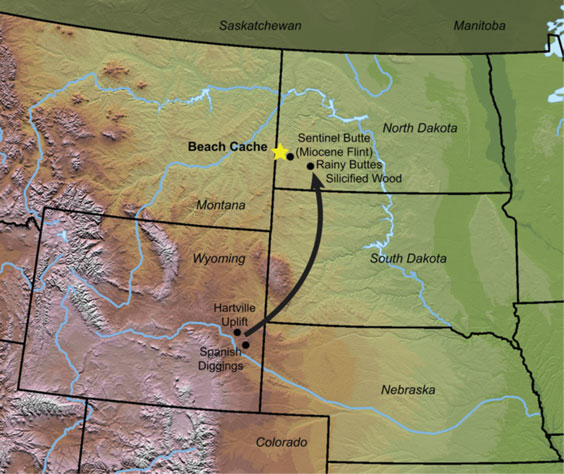

Since late 2020, the State Historical Society of North Dakota has utilized the Artec Space Spider 3D scanner to create diverse 3D models from a range of artifact categories. These include decorated Native American ceramic sherds and a stone axe, grooved maul, glass pendant, ground stone tool, and chipped stone tool. The agency plans to create a virtual display of these and other models on its website. However, a significant challenge associated with virtually displaying these 3D models is the potential for unauthorized reproduction and distribution. It's crucial to carefully consider copyright implications and the intended usage of these models before sharing them online. Access controls and usage agreements can help mitigate potential risks.

In conclusion, the digital accessibility of artifacts democratizes access to knowledge and invites a worldwide audience to engage in exploration and learning. Moreover, 3D printing empowers hands-on engagement with replicas, enriching educational experiences and promoting inclusivity among diverse communities, including those with sensory impairments.

References

Eve, Stuart. 2018. “Losing Our Senses, An Exploration of 3D Object Scanning.” Open Archaeology 4, no. 1: 114-22.

Garstki, Kevin. 2017. “Virtual Representation: The Production of 3D Digital Artifacts.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 24: 726-50.

Graham, Chelsea A. 2012. “Applications of Digitization to Museum Collections Management, Research, and Accessibility.” Master’s thesis, Lund University. https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/lup/publication/2543856.

Montusiewicz, Jerzy, Marcin Barszcz, and Sylwester Korga. 2022. “Preparation of 3D Models of Cultural Heritage Objects to be Recognized by Touch by the Blind—Case Studies.” Applied Sciences 12, no. 23: 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122311910.

Younan, Sarah, and Cathy Treadaway. 2015. “Digital 3D Models of Heritage Artefacts: Towards A Digital Dream Space.” Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 2, no. 4: 240-47.