Why Archivists Love Microfilm

If you’ve ever had a conversation with our reference staff about using the State Archives’ collections for research, you probably heard about or even used microfilm. Most of our popular collections, such as our newspapers and naturalization records, are filmed and stored on microfilm for easy access in the reading room.

Microform is the reproductive process used to produce materials at an incredibly small size. There were originally four types of microform: microfilm, microfiche, super-fiche, and microprints. Microfilm and Microfiche are the only two still created today; here in the State Archives you will most likely find microfilm reels.

Microforms became popular for preserving and storing old newspapers and records in the 1930s and continued to be widely used in businesses, archives, and universities until the 1990s when the PDF became an easy and searchable format for all users. But microforms are still a well-used and well-loved resource for us in the State Archives. Indeed, there are a number of ways using microfilm and microfiche support our archival values of preservation, storage, and context within collections:

1) Preservation: Over time the chemicals used in mass-produced paper causes it to become yellow and brittle, and the paper starts to fall apart. Newsprint paper from the 18th and 19th centuries is especially vulnerable to this decay. By filming the State Archives’ newspaper collection and using the microfilm copies instead of the original for research and reference requests, we can prevent further damage to the material. Another great feature of microfilm is that it is a very stable medium, in that the material of the film does not start to deteriorate as fast as other formats such as paper, which can last about 50 years, or digital file formats, which are sometimes only compatible for 10 years or less. Experts say that microfilm can last for over 500 years if stored in the proper environment. Having a microfilmed copy for researchers and staff to use again and again helps us preserve the original copy for future generations.

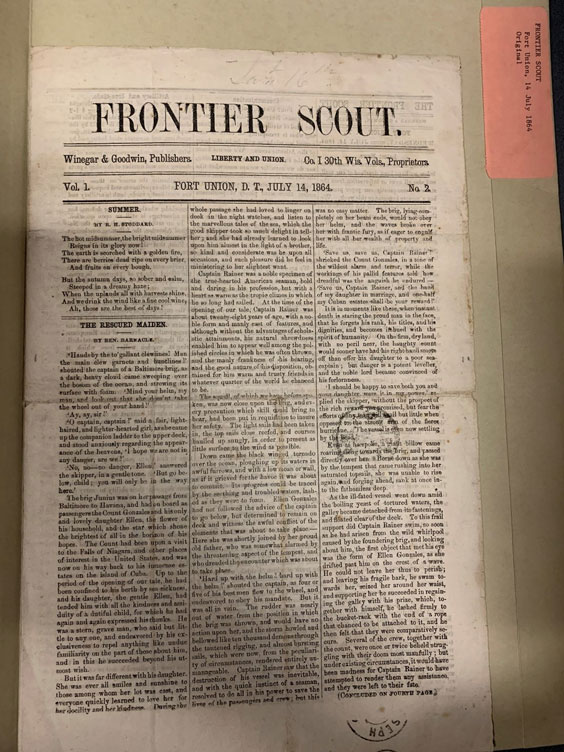

An original copy of the July 14, 1864, edition of the Frontier Scout, the first newspaper published in what is now North Dakota.

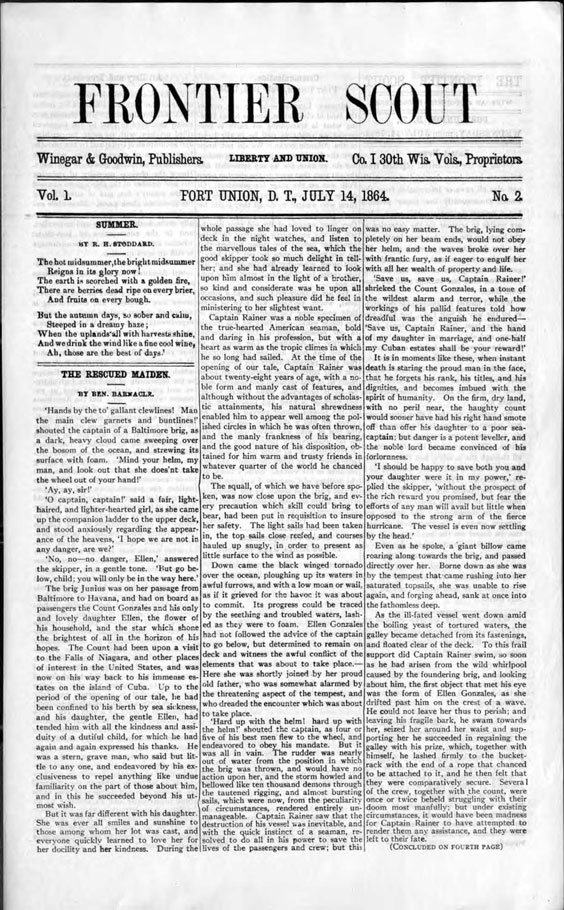

A scan of the same edition of the Frontier Scout from the microfilm roll.

2) Storage: It may seem obvious, but microfilm is a simple storage form that can contain tons of document images while still being compact and lightweight. One roll of microfilm that is 35 mm in size can hold up to 800 newspaper pages, which means multiple years of a newspaper can often be found on one roll. This is also helpful for storing very large collections such as the U.S. census or marriage records. It is much easier for staff and researchers to move and use a small lightweight roll as opposed to boxes full of heavy paper.

Here a microfilm roll is juxtaposed with a physical box of newspapers. A single role of microfilm can contain multiple years of a given newspaper.

3) Context: Archival collections are organized and best researched as a whole so the creator’s original intention and the purpose of the information is as complete as can be. Digitized archival searches that only return individual documents may remove important context. Case in point: If you only look at the one document or article you searched for, you don’t get the information you did not search for. A microfilm machine does not have a search function and won’t allow you to skip the surrounding pages easily, thereby preserving the wider context and allowing facts and information to be studied in the whole rather than in a vacuum.

Finally, the goal of all archives work is to balance preserving and caring for original documents with providing the best and easiest access to the collection in question. Microfilm may appear to be a dated technology to some, but it still fulfills this objective well and is a valuable resource to the State Archives and researchers everywhere.