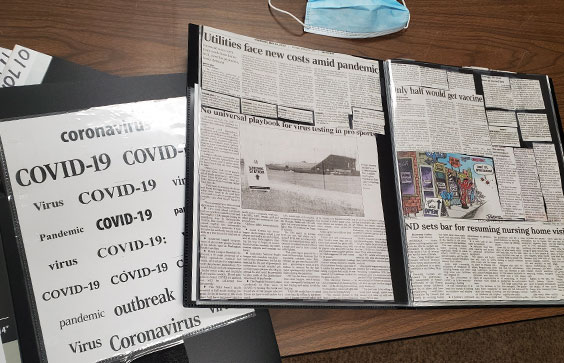

Imagine: The Rewards and Challenges of Beginning as the New Director During COVID-19

Imagine the exhilaration of landing your dream job at one of the leading institutions in your profession. Then, the less exciting tasks of selling your current home, saying goodbye to your award-winning team, and relocating to the other end of the country for your new job on an award-winning team. Throw in the additional excitement of settling into your routine in a new state, purchasing a new home, learning all about your role and the complex organization you now lead. Just think of the exciting new challenges – learning about your coworkers, getting to know how the organization functions, the kinds of things it does, the people it reaches, and of the amazing places you will go. It’s like the first day at an exciting new school, or that first day of college!

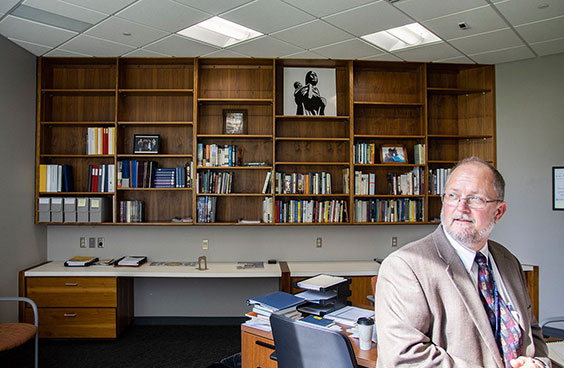

Bill Peterson, State Historical Society of North Dakota Director

Now imagine doing all of that in the middle of the current pandemic. Saying goodbye to the old team was sad. Instead of an emotional hug over a cold beer with people you loved, mentored, and wielded the mighty sword of history with, it was online. It should have been battle-scarred history warriors enjoying a celebratory victory lap with cheers, back slaps, and grandiose tales of unimaginable valor. But it was something else. We still nailed it—we laughed, we cried, we said our goodbyes, and gave our well wishes. But the whole thing was dimmed by COVID-19 virtuality and the flatness of Zoom. We didn’t get fist bumps, and we will never get to have those hugs. Historians will never look fondly upon those pictures. I will never reminisce over those photos of treasured friends and colleagues in our final moments together because they don’t exist.

Fast forward to the first day of that amazing new job. I still rely a great deal on what I can observe. On those first days at the ND Heritage Center, I saw nothing really. There were no people working here, and there were no visitors. It was a modern, post-apocalyptical ghost town. I did observe just how clean and secure the Heritage Center was though. If civilizations from alien worlds were observing us in those days in early June, they would have watched custodial teams cleaning the building to a spotless perfection and the security teams constantly monitoring cameras and installing body temperature scanning systems in the hope of future visitors. The word “eerie” comes to mind.

Custodian Josh Masser mopping the terrazzo floor of the Northern Lights Atrium.

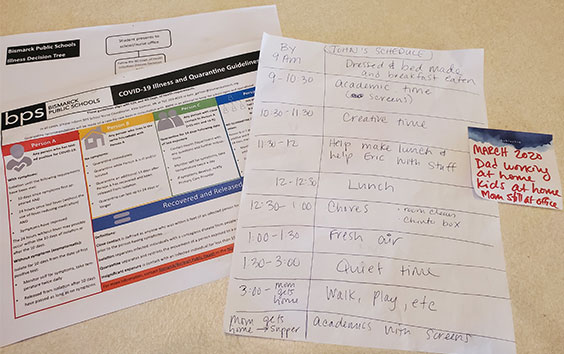

The ND Heritage Center & State Museum reopened to the public June 22. My first official day, after spending weeks with outgoing director Claudia Berg, was July 1. I was able to meet more and more of the staff as they came in from their remote locations to pick up work or to drop off something. They were a bit like science fictional scouts or prospectors returning to the ship for supplies and immediately heading back out to the frontier. Some staff are now back in the building full-time, but there are still team members I have yet to meet in person who are continuing to telecommute. Learning everyone’s name was a challenge for me. I had to work at it. And now, it was all for nothing. Bank robbers wear masks for a reason—they work. I am almost back to square one with learning the names behind the masks.

These first months have taught me just how much I have to learn about North Dakota. Nothing is quite as good at reminding me of my intellectual inadequacies as the bookshelf in my new office. It is quite the bully at 16 feet long by 6 feet tall. I have never had a problem filling a professional bookshelf or case with more than enough materials to impress your average professional. I read. A lot. Yet the hulking, half-full bookshelf mocks me. Constantly lurking behind me, growling sinisterly in my ear in its Stephen King- inspired voice, “I’M NOT FULL! Why am I not sagging beneath of the weight of North Dakota knowledge containers?” The bully never stops. It’s sulking hungrily behind me as I write.

I think I just heard the bookcase say, “FEED ME."

In late July and early August, I traveled to our various historic sites to meet the rest of the teams. They opened to the public as planned on Memorial Day weekend. On these trips, I learned so much and met some of the best history professionals imaginable. We manage some of the most amazing history sites in all the land. I learned another thing about the State Historical Society of North Dakota on those trips too. We love to mow grass. I think we mow the whole state. I am told people love us for this. The grass selfishly kept right on growing during the whole summer. Maybe it is a bit of a bully, too.

Grass, the bully at Fort Buford State Historic Site.

Grass, the bully at the Chateau de Morés State Historic Site.

The green bully at Welk Homestead State Historic Site.

It’s been challenging, but I am learning. This is an amazing institution, staffed by an incredible team of professionals. They are doing great work despite the challenges of COVID-19. I am overjoyed to be here and looking forward to all of the amazing places we will go together. I still can’t see a lot of how things are getting done, but I see the great results.

I know a lot of people have been severely damaged and lost loved ones to COVID-19. Through it all I have been very fortunate, and I am grateful that my wife, Susan, and I have fared so well while so many have struggled. We are delighted to be in North Dakota. If I haven’t met you yet, I look forward to making your acquaintance soon. When you feel comfortable coming to the building, stop in and say hello. To guarantee safe passage, I would bring a book to feed the monster in my office.