Birth Records or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Research

As a recent transfer to the beautiful state of North Dakota by way of Texas, I am learning all the ins and outs of North Dakota information law and how it applies to my work in the State Archives. Being an archivist means providing access to the public; however, due to the sensitive nature of information, state and federal legal statues limit some types of documents that we are able to provide. Although we are limited in releasing some information, there are many more records that you can access that will give you the information you need.

For instance, are you trying to find birth records before the turn of the 19th century? This may prove difficult as North Dakota did not mandate the recording of births and deaths until the beginning of the 20th century, and even after this mandate, compliance was spotty until the 1920s.1 But there are other options to find this information — it may just take a bit more searching.

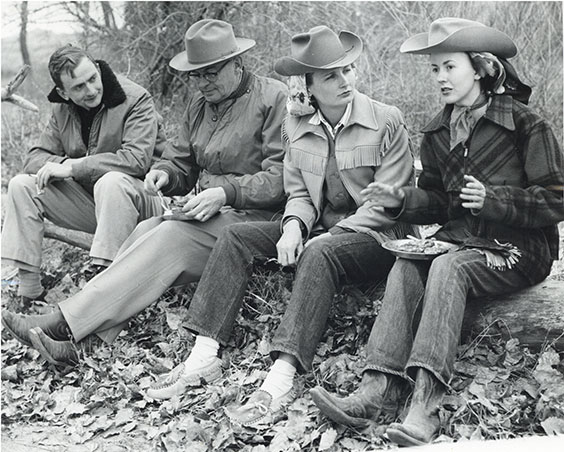

Babies from the Margaret Wilder Welch Naylor Photograph Collection, 1890–1920. SHSND SA 2011-P-002-1588 and 1573

If you are looking for any vital record less than 125 years old, you will have to check with the Division of Vital Records. If you are specifically looking for a birth record that is less than 125 years old, then you must produce documentation to prove you are a lineal descendant.2 A lineal descendant is “a person who is in direct line to an ancestor, such as child, grandchild, great-grandchild and on forever. A lineal descendant is distinguished from a ‘collateral’ descendant, which would be from the line of a brother, sister, aunt or uncle.”3

So what does this mean if you are looking for birth records of your great-great-aunt who was born in 1900? That we at the State Archives cannot release this information. According to the Century Code, you can only obtain your own birth record if you are age 16 or older. Parents can get their children’s record if the parent is named on it. If the parent is deceased, a relative of the parent can obtain a copy. For relatives several times removed, providing this information to the Division of Vital Records is particularly challenging. To compound matters, the Century Code does not elaborate on what documentation is necessary to prove direct descendance.

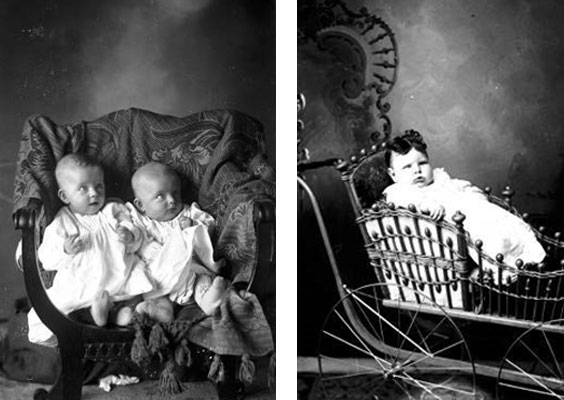

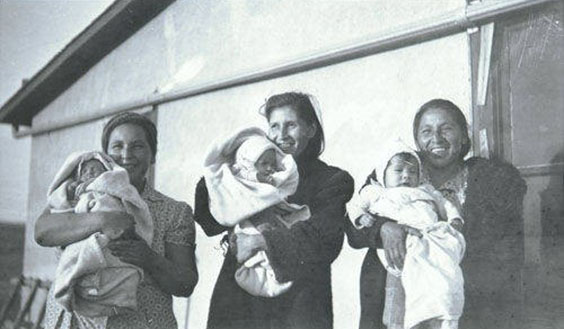

Three women with babies on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, 1930s. SHSND SA 00041-1013

How do you find birth information without providing familial records?

- Newspapers

- Church records

- Biographies

- Naturalization records

- Census records

Above are just a few resources that may provide you with information. Although sometimes these records might prove fruitless, it is always good to check. For instance, you could start by looking through the local paper of the township where your relative lived to see if there are birth announcements in the social pages. You could also try searching for baptismal records at the specific church your relative attended or the administrative body of the religion they practiced. Some of these records are available at the State Archives and other repositories in North Dakota. For instance, if you are looking for birth information about your Jewish ancestors, you may want to contact the synagogue in closest geographical range to where they lived or the Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest. If your ancestors were Catholic, you may want to check with the parish or regional diocese, and if your relatives were Presbyterian you will probably want to call the church they belonged to or the Presbyterian Synod.

These are just a few ways to find birth information without going through the Division of Vital Records for a certified birth record. Again, searching for information may take a little more time and effort on your part, but you might find additional relevant information that you can’t find on a birth record.

1Sixth North Dakota Legislative Assembly of North Dakota, “Vital Statistics,” Ch. 169 in Laws Passed at the Third Session of the Legislative Assembly of the State of North Dakota, retrieved Feb. 6, 2020, https://www.legis.nd.gov/assembly/sessionlaws/1899/sl1899.pdf#page=239; Tenth Legislative Assembly of North Dakota, “Vital Statistics,” Ch. 270 in Laws Passed at the Tenth Session of the Legislative Assembly of the State of North Dakota, retrieved Feb. 6, 2020, https://www.legis.nd.gov/assembly/sessionlaws/1907/sl1907.pdf#page=458; Family Search.org, 8 April 2019, “How to Find North Dakota Birth Records,” retrieved Feb. 6, 2020, https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/How_to_Find_North_Dakota_Birth_Records.

2Sixty-Sixth Legislative Assembly of North Dakota, “Sec. 23-02.1-27: Disclosure of Records” in North Dakota Century Code, 2018-2019, 9, retrieved Feb. 5, 2020, https://www.legis.nd.gov/cencode/t23c02-1.pdf#nameddest=23-02p1-26.

3Legal Dictionary, https://dictionary.law.com/Default.aspx?selected=1168.