National History Day: The Kids Are All Right

I have good news and bad news. First: the bad news—we are living in troubled times. However, that’s not really news. As a historian, I assure you, people have always been living in troubled times. Now: the good news—I have seen the future, and things are looking up. I see the future each year as students from around the state participate in the National History Day in North Dakota contest.

Students and teachers from Elgin-New Leipzig Public School participated in National History Day in North Dakota on April 7, 2017.

The state contest is affiliated with the National History Day contest that takes place in College Park, Maryland, in June. Similar to a science fair, the national contest has been around since the 1970s. If you ever need proof that the kids are alright, I encourage you to visit the National History Day website and review some of the past contest entries. I think you’ll agree with me that these kids are ready to take on the world.

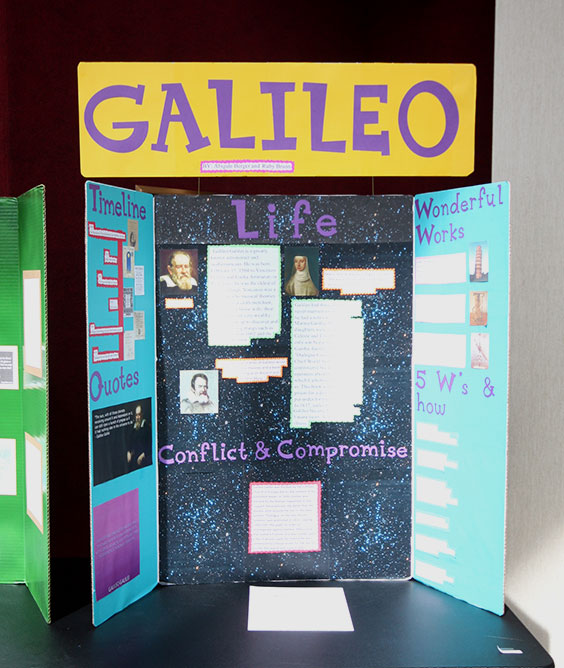

Exhibit Entry, Galileo, from the 2018 National History Day in North Dakota State Competition, Junior Group Exhibit, by Abigale Berger and Ruby Brunn of Dickinson Middle School.

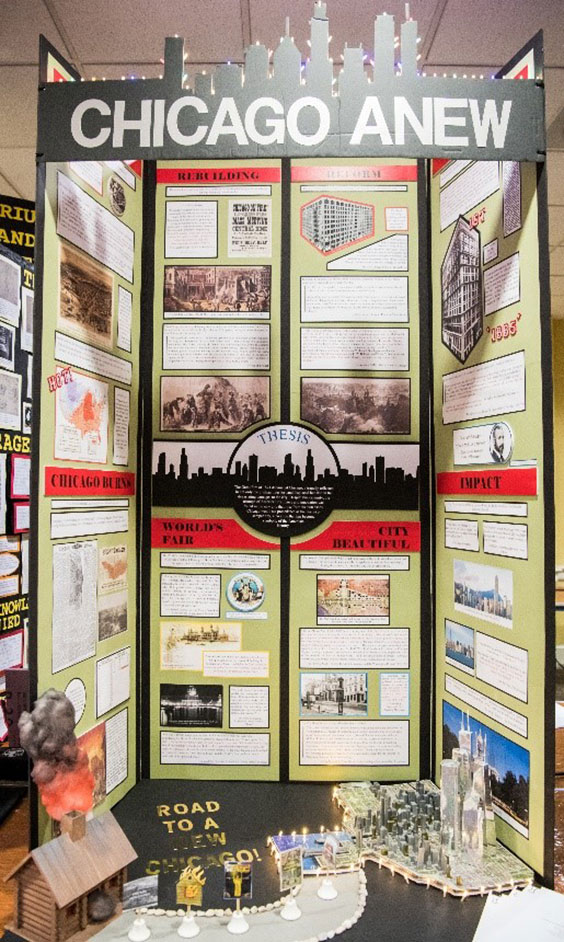

Exhibit Entry, Tragedy of the Great Fire and Triumph of Skyscraper City, from the 2019 National History Day Contest. 1st Place Senior Group Exhibit.

We work with teachers across the state all year to plan the state contest held each April. Workshops for educators and students in grades 6-12 provide a general overview of the program. We break things down into digestible parts that include selecting a topic, conducting historical research, and creating a contest entry. Entry categories include papers, documentaries, websites, performances, or exhibits. Students can work individually or in groups of up to five students. They compete to qualify for school, regional, state, and national contests. We also provide training to help students do more in-depth research, and better understand what our judges are looking for.

Documentary Entry, Echo of Falling Water: The Inundation of Celilo Falls, from the 2019 National History Day Contest. 1st Place Senior Group Documentary.

I’m so passionate about this program because students learn a variety of skills through National History Day, including strengthening their reading, research, and writing abilities. They select a historical topic they are personally interested in, which helps make history relevant and exciting. They flex their creativity muscles in developing an entry for the category of their choice. Research skills help with critical thinking and a build a more rigorous framework to analyze information. If they choose to work in a group, they learn collaboration skills. Explaining their work to adult judges helps them develop communication skills.

Performance Entry, Territorial Diplomacy: Seo Hui’s Compromise and Demands for the Goryeo Dynasty, from the 2018 National History Day Contest. 1st Place Senior Group Performance.

If you are a parent, student, or educator who would like to learn more about participating in National History Day in North Dakota, please contact me, Dani Stuckle, at dlstuckle@nd.gov or 701.328.2794. Our pool of judges includes a wide-range of professional backgrounds. Judges work in teams where seasoned judges help new judges learn the ropes. Contact me as soon as possible to be added to the 2020 judge roster. The state contest will be on Friday, April 17, 2020 at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum in Bismarck. The contest is open to the public.

If you need to know that our future is in good hands, come check these entries out. You’ll go away feeling very reassured that things will be okay. Learn more at history.nd.gov or NDStudies.gov.