But Why? 4 Artifacts in Our Museum Collection That Just Don’t Make Sense

The State Historical Society of North Dakota started its collection in 1895. Over the past 126 years, the museum collection has acquired many artifacts with a unique and important North Dakota story. But every now and then I come across something that really makes me scratch my head. Here are a few that left me asking, “But why?”

1. Samurai armor

Samurai armor from Japan’s Bungo Province, 1775-1860. If you look closely under the nose (far left) you can see remnants of a hair mustache. Fearsome! SHSND 2015.59.1-10

What does a Japanese suit of armor have to do with North Dakota history? Not much. So why do we have it? The museum acquired the armor from Henry Horton of Bismarck in 1938. At that time, museums served as places where people who could not travel the world came to see rare and exotic things. Samurai armor is a prime example.

2. Poodle fur hat and scarf

This hat and scarf made of poodle fur are not nearly as cuddly as one would hope. SHSND 1982.139.2-3

This one needs no commentary. I think you will join me in asking, “Why?” In the spring of 1924 and 1925 Carrie Larson, a mother of five from Benson County, collected hair from her poodle and proceeded to wash, comb, card, spin, and knit it into a child’s hat and scarf. Below is a picture of the poodle.

Carrie’s son Otto Larson and their useful poodle. A very good dog.

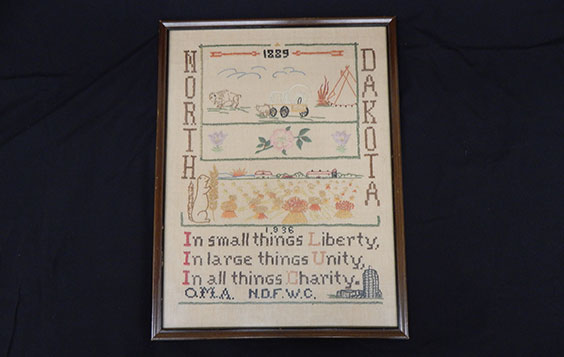

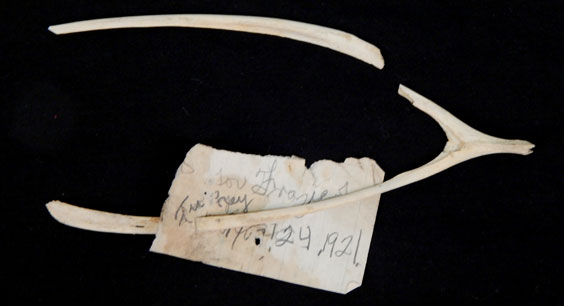

3. A broken Thanksgiving turkey wishbone

I wonder if anyone recalls what they wished for? SHSND 2021.45.1

Museums sometimes have items that are called FICs or Found In Collections. These items have no paperwork, so we don’t know their history or who donated them. The oddest FIC I’ve seen so far is a broken turkey wishbone from 1921. Attached to it is a note that reads: “For Fraziers Turkey Nov. 24, 1921.” While trying to determine why someone would give a wishbone to the museum, I learned former North Dakota Gov. Lynn Frazier’s last year in office was 1921. Any connection between this wishbone and the Frazier’s Thanksgiving turkey is tenuous at best, but I found out some interesting tidbits about the former governor that I need you to know:

- He was a member of the Nonpartisan League (NPL), a political movement which spurred the creation of the state-owned Bank of North Dakota and the State Mill and Elevator.

- In 1921, he became the first U.S. governor removed from office by recall. The next successful gubernatorial recall wouldn’t be until 2003 when voters removed California Gov. Gray Davis from office.

- Frazier named his twin daughters Unie and Versie. Frazier was a graduate of the University of North Dakota and felt his children’s names were a good way to show his school spirit.

4. Hair art

Yes, that is hair. SHSND 11668

Hair art is pretty common in museum collections, but that doesn’t make it any less baffling to me. When I asked Assistant Registrar Elise Dukart why making art out of human hair was so popular during the Victorian period, she aptly responded, “Victorians loved weird, slow activities. They must have had so much time and so much hair.” Rosetta Carroll made this wreath out of her family’s hair in around 1890. Rosetta and her husband, Fred, farmed near Ryder. Although it seems bizarre today, hair art was once a popular craft often used to memorialize loved ones.

These days we are a bit more choosey about what artifacts are added to the museum collection. Our primary focus is to ensure donations fit the State Historical Society’s mission: “To identify, preserve, interpret, and promote the heritage of North Dakota and its people.” We also look for key factors like the item’s condition, whether the donor provided a history of the item, the donation’s similarity to other artifacts already in the collection, and our ability to properly care for it. Still, I am sure we will acquire things that will make future generations ask, “Why?” But then again, asking why is half the fun of exploring the past.