The Magic of Microform

Microfilm. Microfiche. If you work in a museum, archives, or library, or have researched in enough museums, archives, or libraries, you are most likely very familiar with different types of microform. However, you may also be part of an ever-growing group of people unfamiliar with the material or even the word(s). Microform may be an older format, but it is both historic in its own development and highly useful for documenting and preserving items for the future, and should not be underrated.

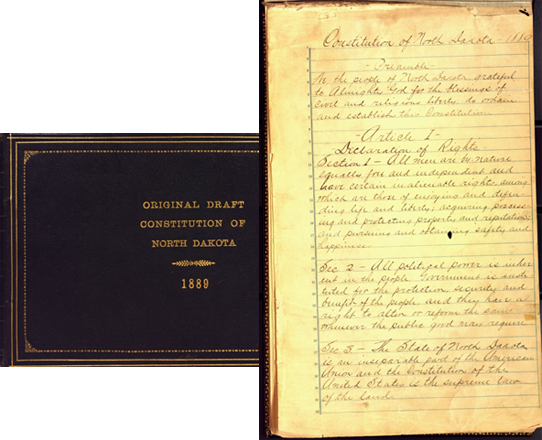

In very basic terms, microform is a miniaturized, reproduced image of an item. (Makes sense, right?) We take something flat, like newspaper or a journal, and photograph each page. Microfilm is developed on photographic film that wraps around reels (and is the form we typically use), and microfiche is developed on a flat sheet. These items can then be used on readers, printers, and scanners, which work by shining light on the image and projecting it out at a larger size.

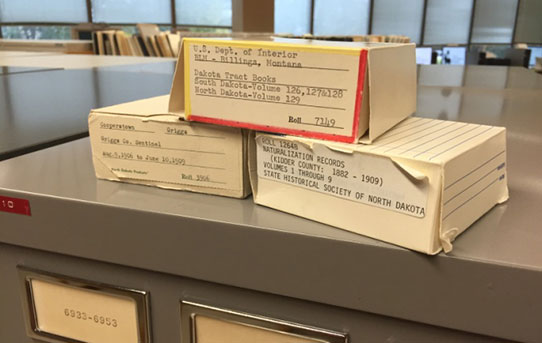

Microfilm is reel-based, like this old roll. A roll of microfilm can hold a lot. One roll can hold a month’s worth of a daily newspaper, such as The Fargo Forum or The Bismarck Tribune; perhaps two years of a weekly paper; multiple small manuscript collections; or several volumes of naturalization or marriage records.

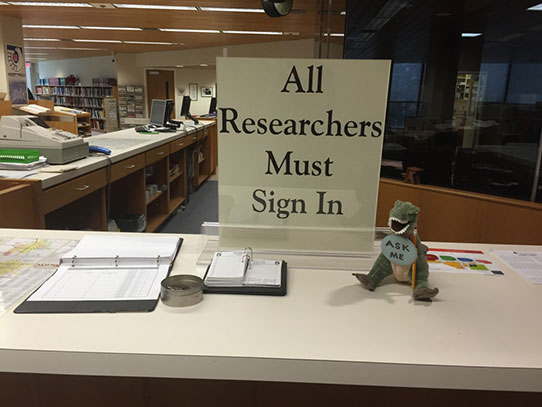

In this world of touch-screen, high-speed internet tech, this may seem old fashioned. Okay, so it kind of is. Microform was actually developed in the mid-1800s, and was considered something of a novelty at first. The State Historical Society of North Dakota only began microfilming newspapers and other frequently used and/or fragile items in the 1950s. We are still microfilming today. This is evident in our Reading Room, where we have more than 16,000 rolls available for public use. The majority of this number encompasses newspapers from around the state, naturalization records, small manuscript collections, and an ever-increasing count of marriage records from various counties, pre-1925. We have masters to most of this film and other microform within collections stored away in more controlled environments.

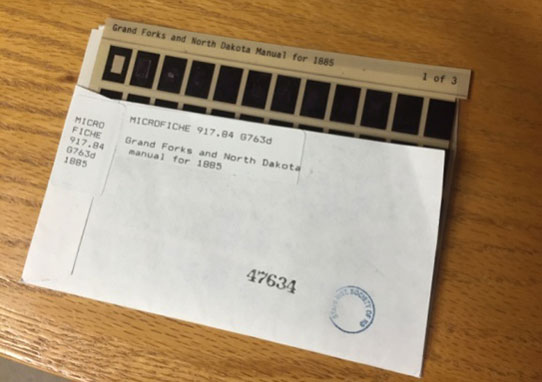

Microfiche like this is a flat sheet. Each square represents a frame of film, which will include one image—in this instance, a page of The Grand Forks and North Dakota Manual for 1885.

Microfilm is not going away anytime soon. There are many reasons why. Microfilming allows us to capture a copy of an original that likely is in the process of deteriorating without handling it and possibly making it worse. It is relatively low cost to produce, maintain, and store; equipment needed to access microfilm is simple enough to use (really, all you need is some light and a method of magnification); the material is supposed to last hundreds of years; and the format is stable. The alternative, a more up-to-date digital file, can indeed be easy to access on the technology so many use on a daily basis—but takes time and money to digitize and store, requires vigilance in the case of updates and reformatting, and has an unknown (and possibly, in some cases, short) shelf-life. Also, it is noteworthy that digital items are not automatically OCR (optical character recognition)-capable. (That means you can’t necessarily search documents by key word, just because they are scanned.) For all of these reasons and more, many agencies continue to use microform for storing and accessing their files. This includes, or perhaps is led by, the National Archives and Records Administration, which succinctly highlights these very comments on its site.

You can see by the condition of our microfilm boxes that they take a lot of use. Is microform the next Holy Grail?

Despite the fact that we use microfilm all the time, in my front-desk capacity at the State Archives, I meet a lot of people who don’t. They run the gamut of ages, but there is definitely an upward tick in the younger age groups. I like to try to explain things in terms that make sense to people. I got pretty excited when I saw Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull for the first time—for no other reason than our hero was trying to obtain microform in one of the scenes. It’s my overwhelming memory of the film, which perhaps says something about the film—I’ll allow you to draw your own conclusions there—and it has led me to reference the film with certain age groups who enter our building.

Me: Hello, students who were not yet born in time to remember Y2K or 9/11!

Students: (mumble, mumble, mumble)

Me: So, do any of you know what microfilm is?

Students: (blank stares)

Me: Have any of you seen Indiana Jones? (Pause as students raise hands.) The last one? With the Crystal Skull?

Students: The first one is my favorite!/I just saw (insert latest move here)!/I liked that one!/I didn’t like that one!/etc.

Me: Remember when he was in the library? (Trying to disguise the fact that I barely remember that scene anymore, except to use it for this purpose, and hold up a disheveled little box as if it’s the greatest treasure on Earth.) This is what he was after! Microfilm!

Students: (Mixed reactions…perhaps not as excited as I am.)

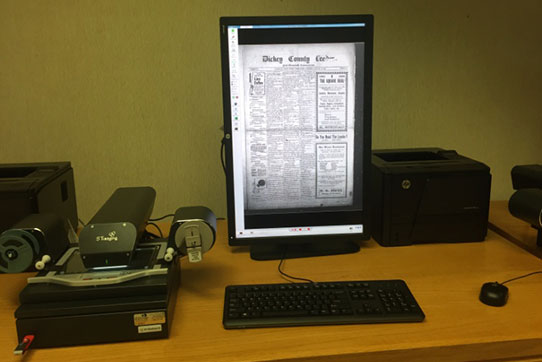

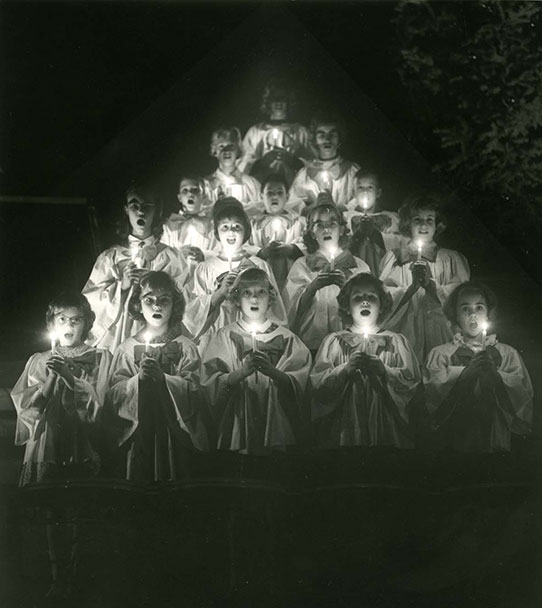

Then I show them how it works. Just like movie magic, it’s actually seeing the microfilm on screen (in this case, on a microfilm reader/printer/scanner) that produces the best response. Once the film is loaded, and people of all ages find their own birth announcements, their great-grandfather’s naturalization record, a picture of their mother or father on the front page of a newspaper… it’s worth it.

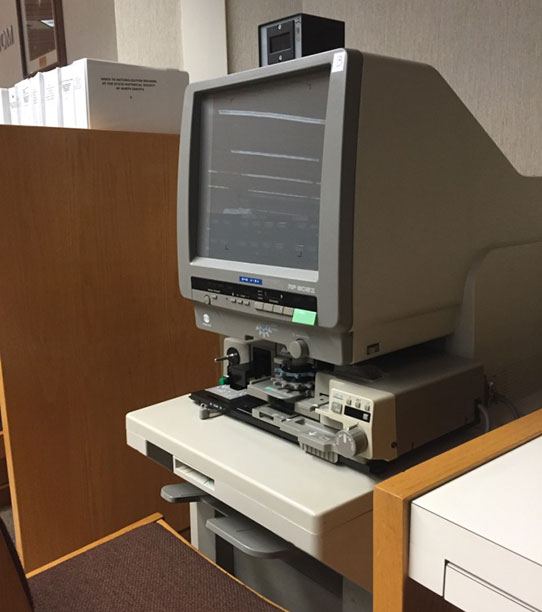

The old technology of microfilm printers like this one was cutting edge back in the day; it is still useful, but does not offer the same options as the new types of machines.

That’s the miracle. It’s not the microform itself, but that we have something that can offer us such stability, and that we thus have the capabilities of making these items so accessible. The miracle is being able to use this format.

We recently acquired these modern microfilm scanners. They work on the computer and provide the user with more flexibility in making copies. They also can scan to a USB drive, which some researchers prefer to the older ones, which only print out paper.

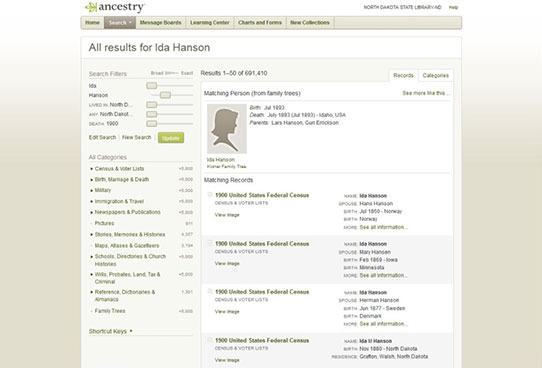

Unfortunately, there are too many Ida Hansons to pick and choose one and hope for the best, especially without more information! This can work, sometimes, but not with this number. Sorry, lucky duck, but you have to recheck your facts. Jump to the

Unfortunately, there are too many Ida Hansons to pick and choose one and hope for the best, especially without more information! This can work, sometimes, but not with this number. Sorry, lucky duck, but you have to recheck your facts. Jump to the