Chronicling America Website is Superhero of Online Newspaper Searches

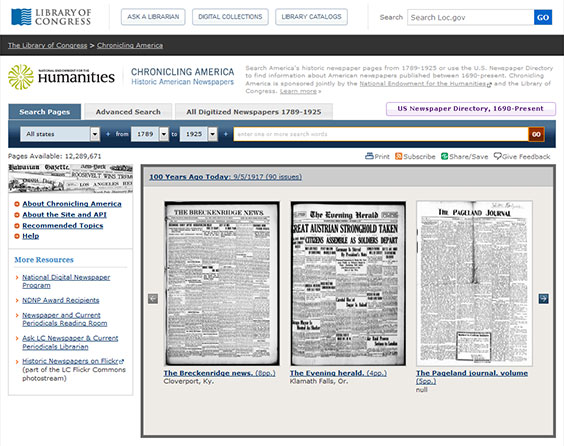

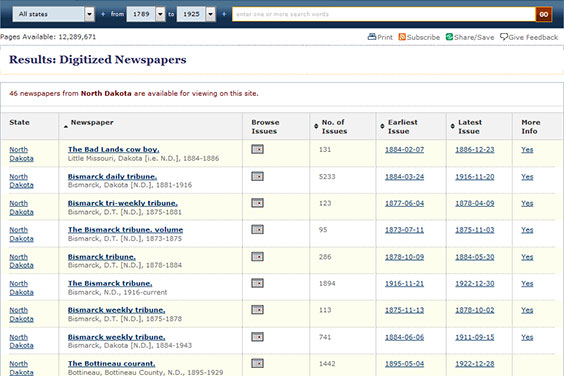

Chronicling America homepage

Chronicling America is an incredible online newspaper resource available for the public through the Library of Congress. Imagine this: there is a free-to-use database where you can search big city and little town newspapers within the United States. You go to the database, select a year range (1922 and earlier only at this point), select a location, type in a key word—and get results that can be viewed, enlarged, reduced, printed, and saved.

Curious about World War I? Here are some headlines. Searching for info about prison breaks, weather, government officials? Just type in your criteria and search—Chronicling America is OCR/word-searchable, which is so great! Our State Archives newspapers on microfilm are not indexed, so typically, if you want to find some information about your family, you have to search day by day, looking at each page. Not so with Chronicling America. You can just type in a name, and see what results come up!

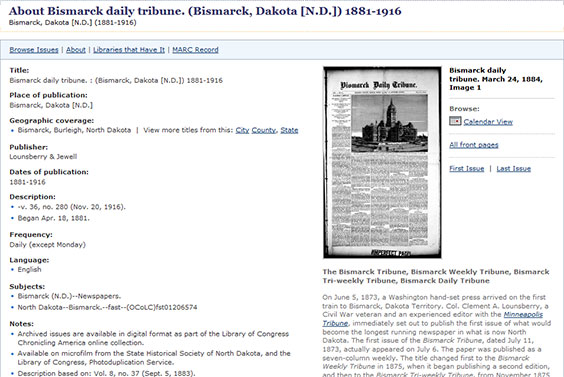

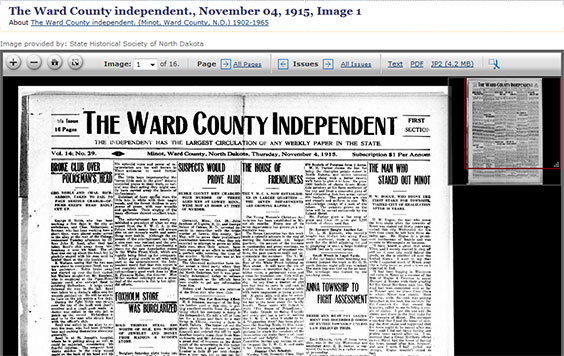

Since 2011, we have received four grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities allowing us to add over 400,000 pages of newspapers to the site. Since not all newspapers can be included, we have selected papers from all over the state containing a lot of local news coverage. This includes papers such as the Ward County Independent, a weekly newspaper; the Bismarck Tribune, a daily; and newspapers from Grand Forks, Devils Lake, Steele, Williston, and other areas.

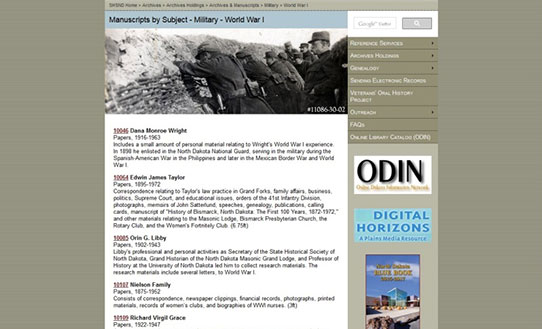

Some of the ND newspapers available on Chronicling America

One caveat to keep in mind; not all news was published in the newspaper. Chronicling America, or newspapers in general, are not a catch-all. Using this site can be a great, easy way to start a search, though, and can sometimes bring up results you might not expect to see.

For example: I received a search request about three years ago from a woman who was looking for a relative who had passed away in, she said, about December of 1902. We looked in multiple papers without any luck. A search of our link to the Vital Records death index did not show the individual dying within a ten-year span—not uncommon, especially around 1900 and through even the 1920s. There were a lot of errors and delays in reporting deaths in those early years. So I had to reply that we were unable to find anything.

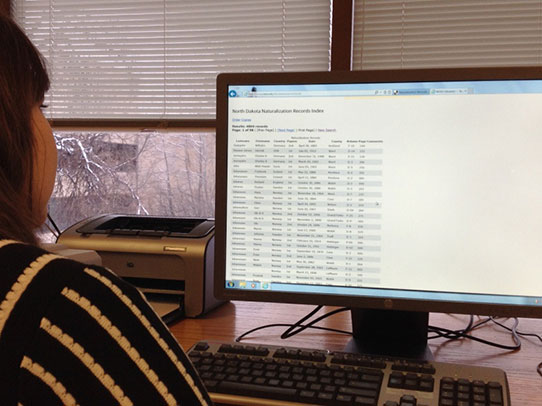

Info about one of the papers available, the Bismarck Daily Tribune, on Chronicling America

Usually, that would be the end of it. However, I kept her request, and just recently, I came across it again. Just for fun, just to double check, I typed the name into Chronicling America, hoping I might find the relative’s name in a gossip column, visiting the city.

Instead, I found a death notice—a year later than the information she had provided!

It turned out, the gentleman in question had died in 1903, not 1902, and passed away in a different city. I was able to respond back, three years later, with an actual obituary. It always is disappointing to us if we can’t provide any information for these requests, so believe me when I say I was very excited to write to her again—possibly as excited as she was to receive the information!

As amazing as this all is, however, it is not possible at this time to put all of our newspapers online. This is something we are asked about frequently, and I do want to clarify that we are not planning to digitize our entire newspaper collection. The amount of time, space, and funding necessary for a venture like this is staggering. We are the official repository for newspapers from across the state, which means that newspaper titles from each of the 53 counties in the state are supposed to be sent to us on a daily or weekly basis. Considering that there is more than one newspaper for some counties, as well as the fact that we keep papers from the past—well, this adds up. Our rolls of microfilm number more than 17,500 already, and the majority of these rolls are microfilmed newspapers. One roll can hold about two years of weekly newspapers and about one month of daily newspapers.

A view of the front page of one ND newspaper, the Ward County Independent, from November 4, 1915, p1 on Chronicling America

I asked one of our staff about the more technical details for this. (If technical isn’t your jam, skip to the next paragraph!) If we were to scan each of our newspaper pages at 300 dpi jpg, which is an average and sometimes even larger image than you might get from a camera phone, we would need around 3.5 Petabytes, with no end in sight to more needed storage. Do you know what a petabyte is? It is approximately 1024 terabytes, or a million gigabytes of storage. That is incredibly huge. And that isn’t even providing for a high resolution image. That image would likely not be able to be enlarged or used in a display; it would be too small. That is also without making these newspapers OCR/word searchable, by the way.

So for now, I would encourage everyone to check out the incredible and amazing superhero of newspaper websites—Chronicling America can be a lifesaver in the world of newspaper searches.

SHSND 10200-00069. ND photographer Nancy Hendrickson’s photo of this bunny makes it look easy to be a superhero—but it’s not!