It’s So Hard To Say Goodbye: Getting My Kids To Donate to the State Collections

One of the best parts of my job is sharing it with my kids—even if they don’t fully understand it. They know that I travel to state historic sites, but they think that means I work at a different place each day and have offices all around North Dakota. They often ask to come with me to help. This past spring, both my son, Calvin, and my oldest daughter, Auri, traveled with me to explore the sites I manage, and in Auri’s case, helped lead Victorian-era games on the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site’s lawn.

Calvin hangs out with Buford the Baby Bison at the Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence State Historic Site near Willison.

Auri and I in front of the Chateau after teaching Victorian games at the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site.

Recently, they had the opportunity to experience a different aspect of my work by donating items to the State Historical Society of North Dakota’s collections.

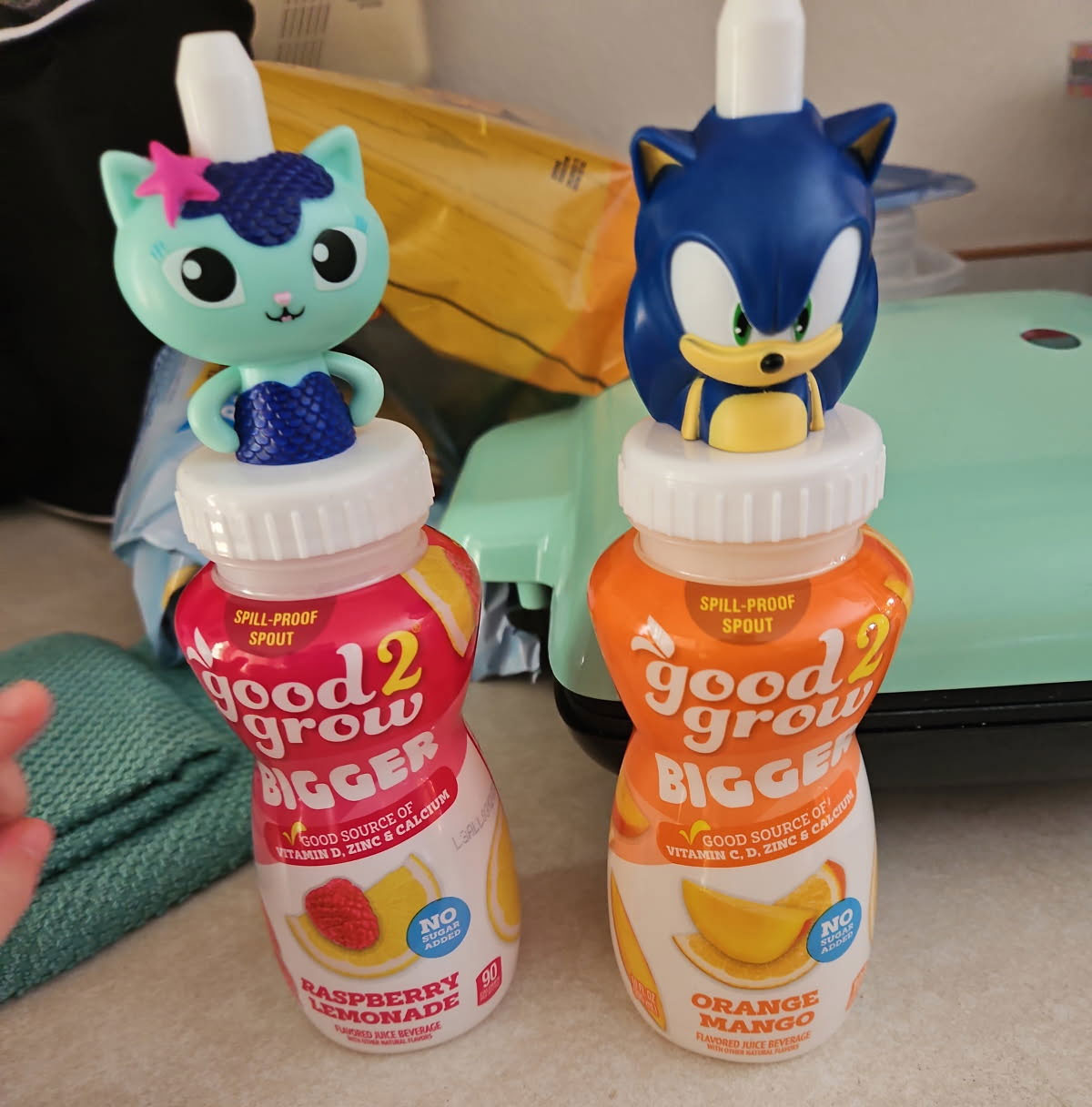

If you are like our family and have kids the same age as mine (5 and 3 years old and 6 months), then I am sure you are fully aware of good2grow juice. Incredibly popular with kids and parents, these bottles have distinctive colorful toppers featuring well-known cartoon characters.

As parents, we appreciate that the juice is not full of sugar, and the bottle is spill-proof. (Well, almost as my wife recently found out. Pro tip: Don’t throw a full bottle down a flight of stairs.) This makes them great for car trips and road trips. The bottles are reusable, so we can refill them with water if we want. When out running errands or on road trips, our kids often pick a bottle of this juice with a character they love as their treat for that trip or for being good.

Our topper drawer at home. Do you recognize any of these characters?

If you are aware of this phenomenon, then you may also, like us, have a massive collection of bottle toppers. We are nearing 100 of these character toppers. And believe me when I say, you can’t just throw them away! My wife has seen numerous videos where parents turn these bottles and toppers into games, such as bowling, cut off the character to make a toy, or even reuse them on a straw for a different cup—basically, try to find any use that keeps kids happy about not losing a potential toy or their favorite character. So what does this have to do with my work for the State Historical Society?

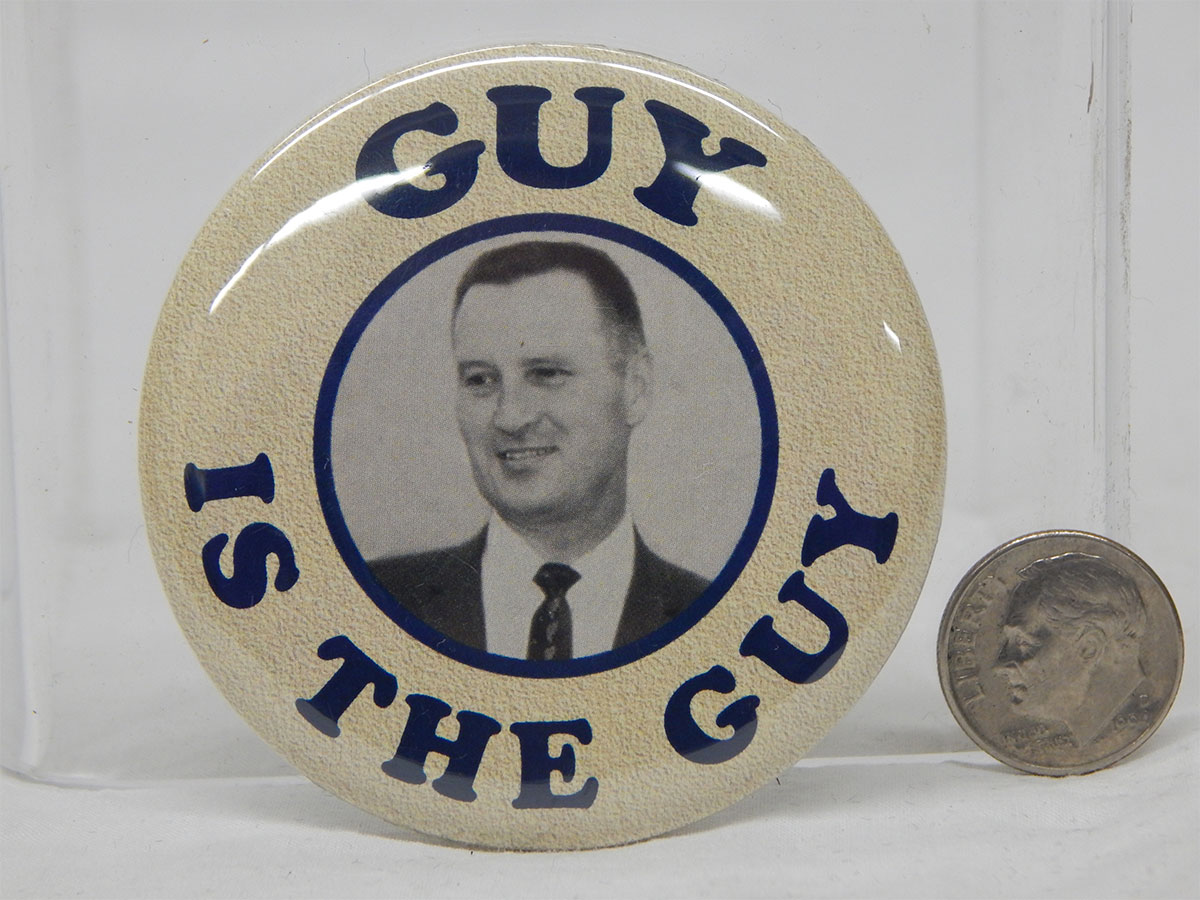

One of the highlights of my job is serving on the museum collections committee. I get to see all the great things people offer us for our collections. We can’t take all of it, as sometimes the item does not have a North Dakota story or maybe we already have a similar item in our collection and do not need another. We try to collect things in the moment, so we don’t have to hope that somebody donates them to us in the future. These bottles and toppers seemed like a good candidate. They are wildly popular now, but they may not be in the future. They are the kind of item the State Historical Society could put on display someday, and parents could explain to their kids how they loved these bottles as children and tell them about the characters they collected. The biggest trick here was convincing my kids to part with a pair of precious bottles.

When I told Calvin and Auri about my idea of donating a pair of bottles and toppers to the museum collections, they were excited. We spent an hour digging through our topper drawer (yes, I know), looking at all possible options. At first, Calvin wanted to donate one that he did not care about—a character from Cocomelon he had initially selected because it was a cartoon head. I told him it should be a character that holds meaning for him. So he selected a Mickey Mouse one, and Auri chose a Minnie Mouse one. Great selections, in my view, as they once went as Mickey and Minnie for Halloween and love those characters.

Calvin and Auri as Mickey and Minnie for Halloween 2022.

The more we discussed it, the more concerned Calvin became that he would never get to use the Mickey topper or see it again. He was also worried it might break or that the State Museum might get rid of it. It was an opportunity to explain to him how our museum’s curatorial staff collects and preserves items for future generations. I told him one day it might even be on exhibit.

Calvin opted to switch to a character he had a duplicate of instead of his one-of-a-kind Mickey with a green hat. He chose Sonic the Hedgehog. He has been a big fan of Sonic since the second movie came out. He even has a placemat with characters from one of the animated Sonic TV shows, each assigned to a member of our family (Sonic = Dad; Tails = Calvin; Amy Rose = Auri; Knuckles = Mom). Auri changed her selection to MerCat from “Gabby’s Dollhouse.” This popular children’s show on Netflix features a girl who shrinks down to the size of a toy and embarks on adventures with imaginary cats inside her dollhouse. Auri and Calvin like the show and have their own version of the dollhouse, along with many toys to accompany it. Both Sonic and MerCat are characters who mean a lot to them.

The final bottle and topper selections earmarked for the state collections.

With the bottles chosen, the next step was to submit the paperwork for potential acquisitions. I handled this part. It is a pretty simple form to fill out. The most crucial part was sharing the history and why I thought these items should be added to the collection. While these bottles do not have a strong North Dakota story, they are items that kids all over the state will remember after they grow up.

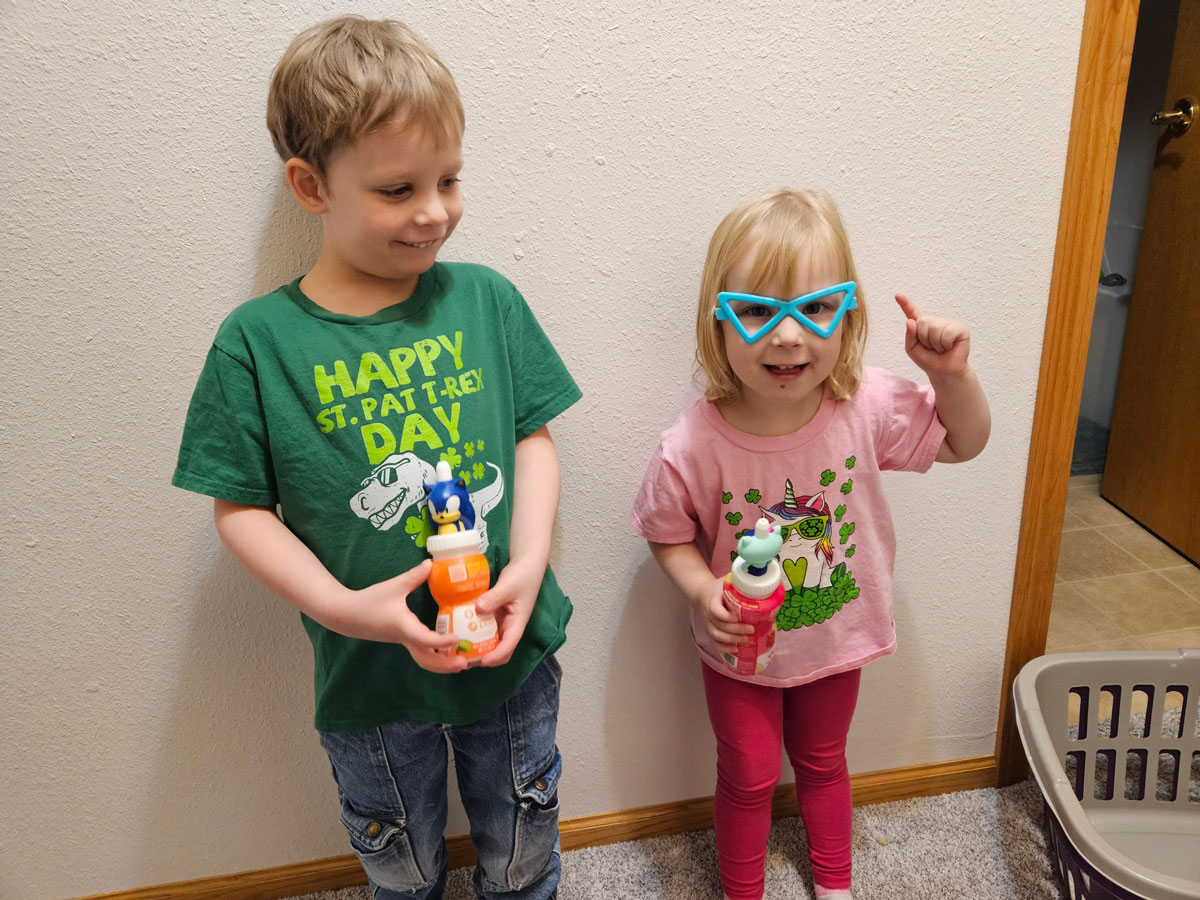

At the meeting, the bottles were received with great enthusiasm and quickly accepted. Our department’s Administrative Assistant Kiri Stone wrote a great note to the kids, telling them that their bottles had been accepted into the collection. For most people who wish to donate items to the State Historical Society, getting such a notification would be a thing of joy. But my kids were sad—their bottles were going away. To ease the pain, I told them we would take photos of them with the bottles so they would never forget them.

Calvin and Auri pose with their bottles before handing them over to the State Historical Society.

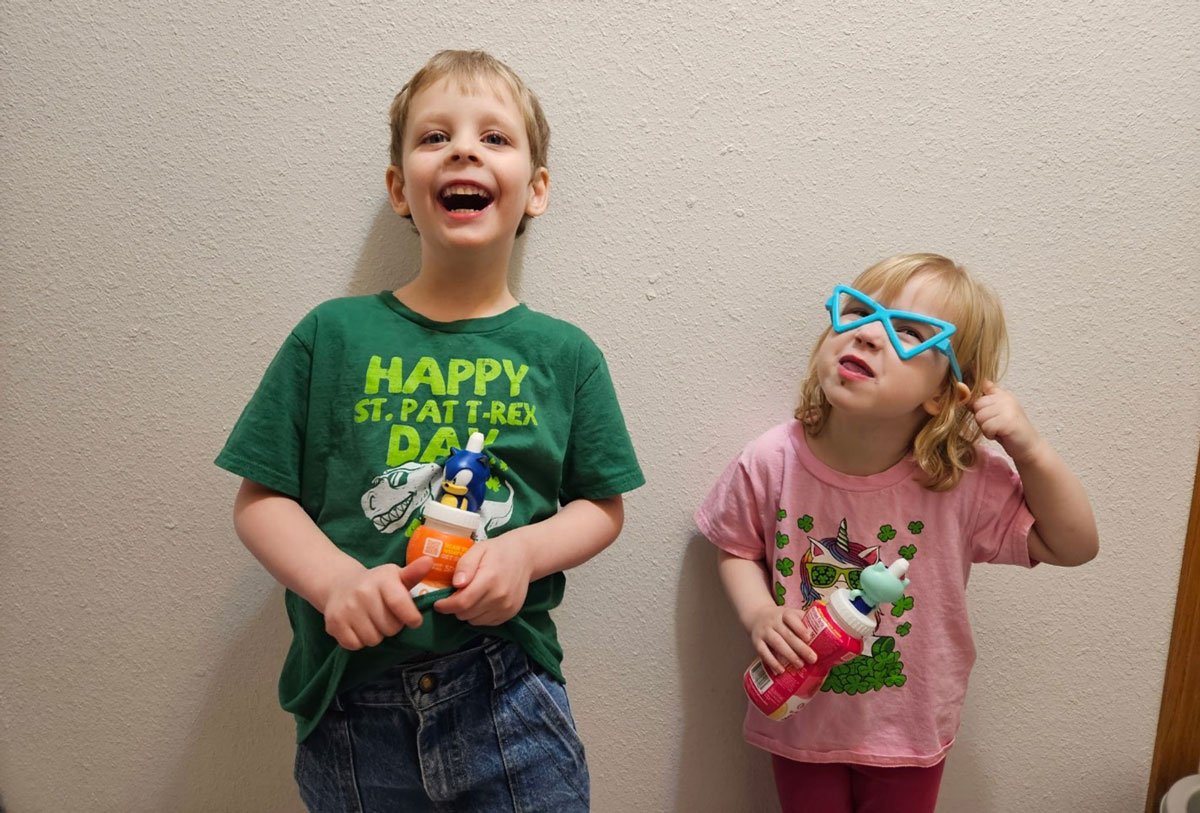

My silly and wonderful kids with their prized juice bottles.

Throughout this process, I constantly explained to them the reasons why we collect items and why these remain at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum. Nobody would use their bottles, I promised. Another challenge was that the bottles would not be going on display right away, and I could not tell them if or when they ever would be. To them, it might seem like they would never see their bottles again. But good old dad had one more trick up his sleeve.

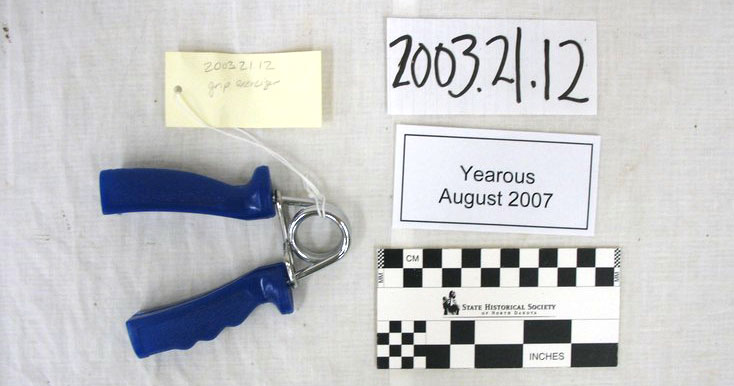

Before I could put my plan into motion, I had to give the collections team time to process the bottles. When an item arrives, it does not go straight back onto a shelf. It must be labeled, a condition report created, photos taken, and data entered into our records management system. A proper home for it also needs to be found. Once this was finished, I could enact my plan. I arranged for the kids to come and inspect the new home of their bottles as well as see some of the other cool things we keep in our collections.

This October, Research Historian Lori Nohner agreed to give Calvin and Auri a behind-the-scenes tour of the museum collections area. The kids were ecstatic about the opportunity to visit Dad’s work and also be reunited with their bottles. Lori did a great job of showing the kids around the collections. Seeing their bottles was a highlight but so was seeing a pair of nursing scrubs that belonged to their mom and their dad’s name badge from his teaching days. They also got to see some historical toys. They loved that Lori let them use her badge to buzz into collections and help her move shelves. Overall, it was the perfect way to cap off this whole experience.

Research Historian Lori Nohner takes Calvin and Auri to see their bottles’ new home.

Calvin and Auri are excited to see Mom's scrubs that she donated after finishing nursing school. My wife was also excited to see them. Baby Zelda was ready for a nap.

Lori shows my kids a nurse’s outfit that was over 100 years old so they could compare it to their mom’s donated scrubs.

Auri helps Lori move the collection shelves.

The whole experience was great. I know my wife and kids got a kick out donating to the museum and going behind the scenes. We don’t often think the items we use every day and take for granted have historical value. Or we feel the need to hold on to them until they are old enough to warrant donating. Now my kids can claim to have items in a museum and may continue to share items in the future. And for readers of this post, perhaps you have something we need to better tell the story of North Dakota and its people, even if it is not 100 years old.

Auri says, "All this history stuff is hard work."