Medora From the Air

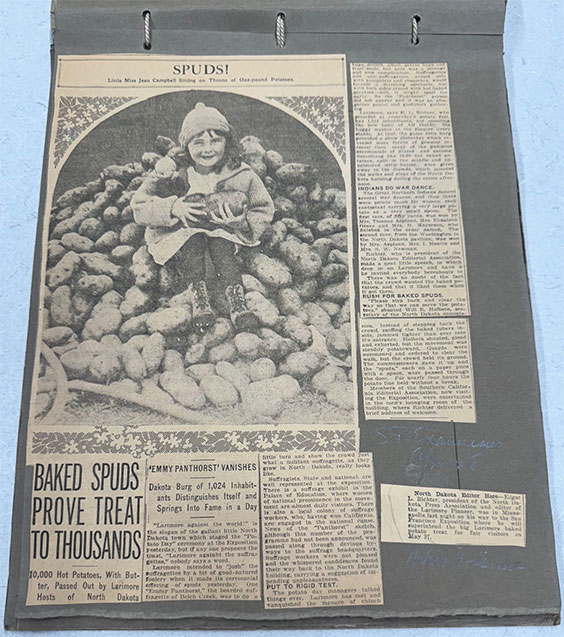

The town of Medora is a gem of western North Dakota, but how much do you really know about the person it was named for? An exciting exhibit opening later this month at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum celebrates the accomplishments, fascinating life, and artistic skill of the town’s namesake, Medora Manca.

Medora von Hoffman was an American heiress from New York when she married into French aristocracy, and her history has often been eclipsed by that of her more flamboyant husband, Antoine Amédée Marie Vincent Manca Amat de Vallombrosa (commonly known as the Marquis de Morès). In addition to learning about the often-overlooked life story of Medora (the person), visitors will have the opportunity to view more than two dozen of her spectacular watercolor paintings. Many of these watercolors were painted between 1883 and 1886, and some are publicly displayed for the first time in the exhibition.

These two images of Medora from the upcoming exhibit celebrate the duality of her background, that of a wealthy heiress and an adventurous spirit living in Dakota Territory during the years 1883-1886. SHSND SA 00097-00038, 00042-00081

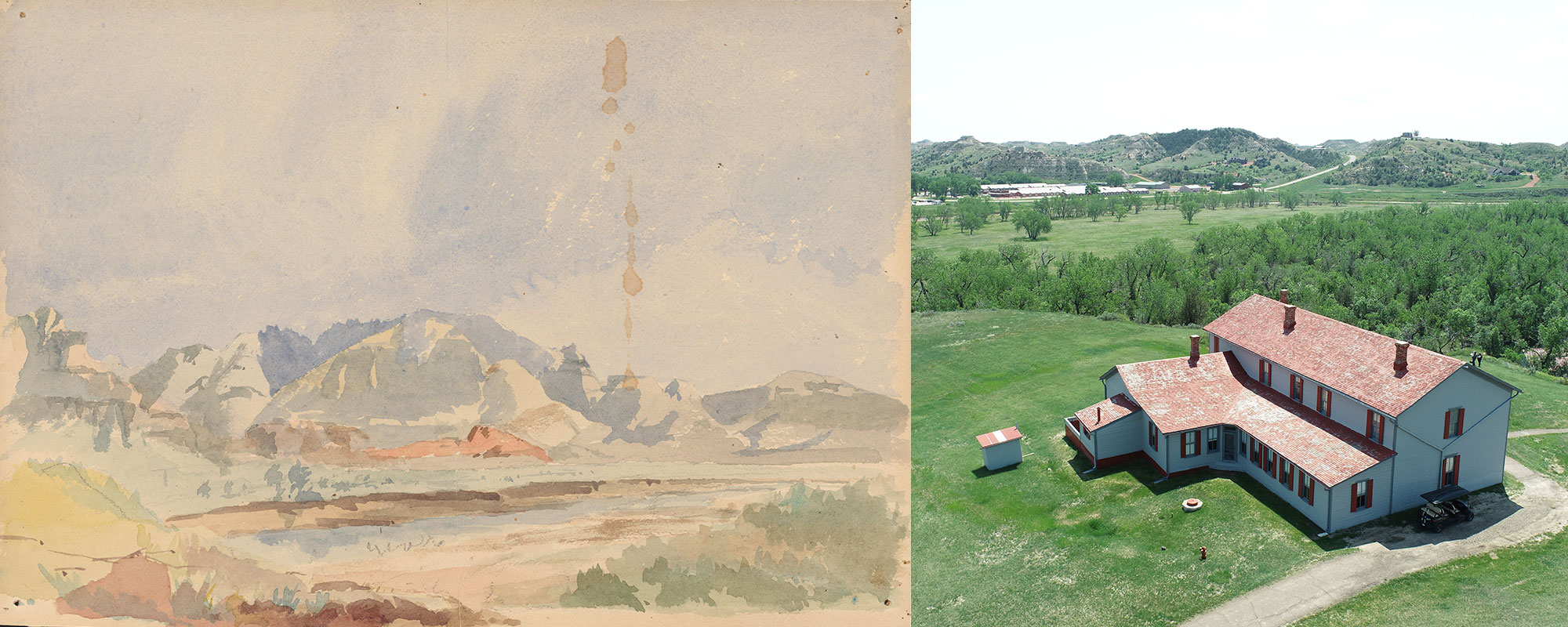

Medora painted landscapes and scenes around their home at the time, the Chateau de Morès (now a state historic site). The scenes were painted outdoors (“en plein air” in French), and many of the landscapes and buildings depicted will be familiar to visitors acquainted with the rugged beauty of the Badlands.

The Little Missouri River, the city of Medora, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park are all visible in this image captured via an uncrewed aerial vehicle operated by agency staff in June 2025.

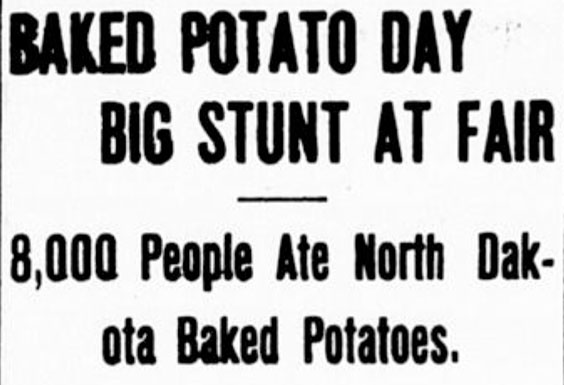

State Historical Society of North Dakota archaeologists recently conducted research in Medora related to a military encampment (called a cantonment) that housed soldiers guarding the early railroad being built in the area. The cantonment was active from 1879 to 1883. The research we’re doing is helping document the former location of the cantonment in advance of a planned project.

To accomplish this, researchers are using historical documents, field research, geophysical remote sensing equipment, and uncrewed aerial vehicles (or drones). The work is a cooperative project of the State Historical Society and the Theodore Roosevelt Medora Foundation. The research and analysis are ongoing, and we continue to learn more.

Above left: Troops stand in formation in front of a barracks located at the Medora cantonment in this 1880 photograph. Note the Badlands landscape visible in the background of this historical photo. H-00305b, Montana Historical Society Library & Archives, Helena, Montana

Above right: An image of that same location from June 2025.

Below: Architectural plans of the cantonment barracks from 1879. National Archives (photo no. 205135316)

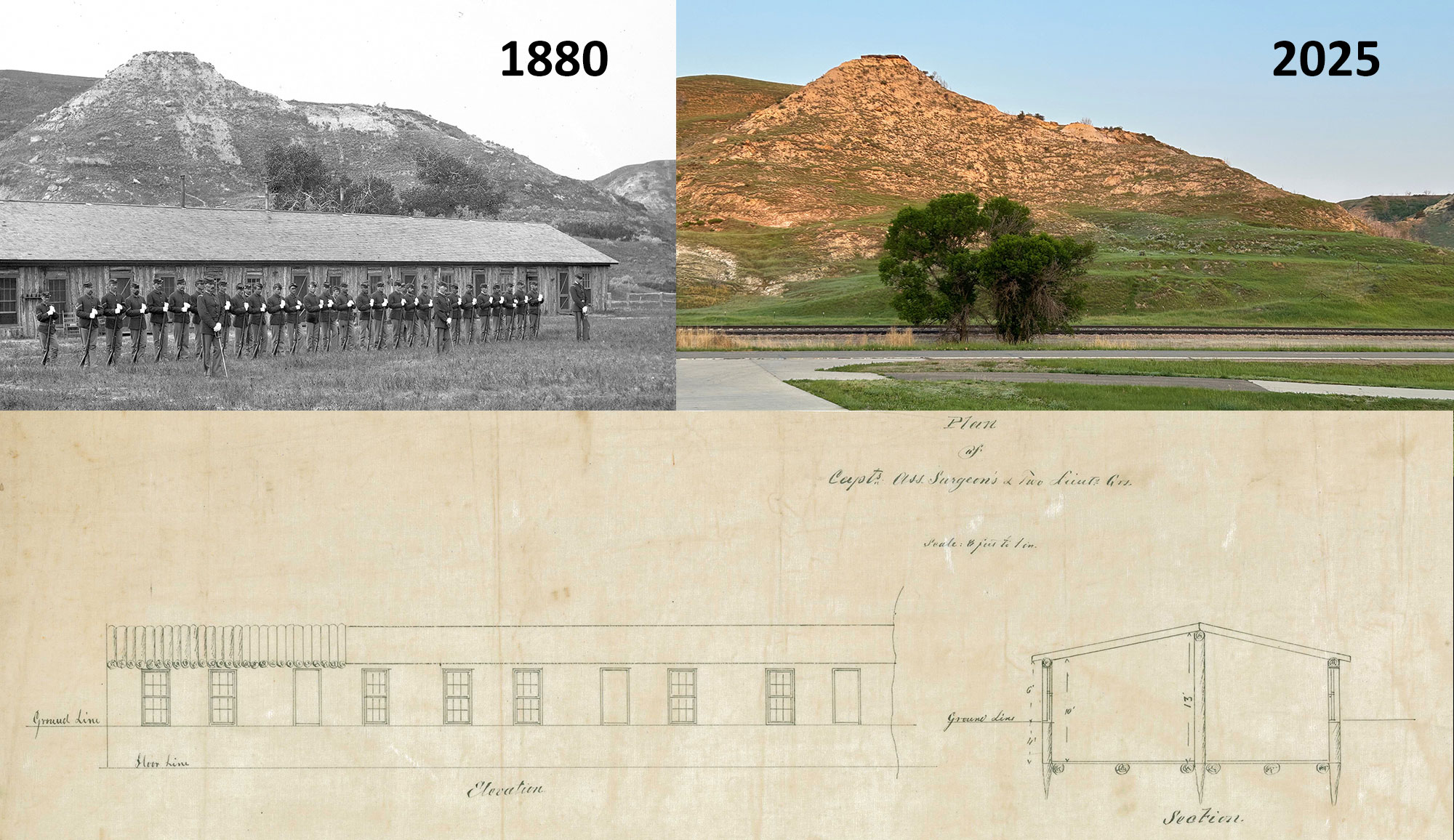

The research location also provided an opportunity to try to replicate some of the vantage points Medora used while painting these watercolors. Aerial photography with the drone allows us to consider the beauty of the rugged landscapes around Medora (the city) and to appreciate them as Medora (the artist) may have. Her paintings document a significant period of history in North Dakota, and her skill as an artist is impressive!

The author and colleague Erica Scherr use an uncrewed aerial vehicle to capture images around Medora, June 2025. The Little Missouri River, the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site, and the town of Medora are all visible in the background.

In June 2025, Historic Preservation Specialist Erica Scherr and I captured drone images that will be paired with several of Medora’s watercolor paintings from the exhibit. The images depict many of the same Badlands landmarks visible in Medora’s 1880s artwork. The perspectives are shifted slightly, as she obviously didn’t paint from the same height as a drone. But you can still get a sense of the relationships among objects and the landscapes that Medora Manca experienced as she painted.

Left: Watercolor of the Chateau de Morès and nearby outbuildings by Medora Manca. SHSND 1972.91

Right: A State Historical Society drone image of the same location, June 2025.

Left: Watercolor painting landscape by Medora Manca. SHSND 1982.29.73

Right: State Historical Society drone image of the Chateau de Morès, June 2025. Note the Badlands formations depicted in the painting above are visible in the background. View is to the east.

Aerial photography is a valuable tool that allows us to both document the history of Medora (the city) and appreciate how Medora (the artist) interpreted the beauty of western Dakota around her. A view of the area from the air is a unique way to further appreciate Medora’s adventurous spirit and admire the way she expressed herself through art.