One of the most important artifact types found in archaeological sites are ground stone tools. These include tools such as stone axes, manos, metates, pestles, abraders, figurines, and hammerstones. Most ground stone artifacts were created by pecking, grinding, and polishing. Additionally, drilling was used to create holes in scarcer ground stone artifacts such as smoking pipes, stone gorgets, and stone pendants. In contrast, artifacts like manos, metates, and hammerstones could be selected from natural cobbles and slabs and used with little or no modifications. While manos, metate, mortars, and pestles are often used to process substances (e.g., plant and animal products, pigments, clay, and tempers), hammerstone, abraders, and polishers are mainly used to manufacture and shape tools (Adams 2014; Morrow 2016).

Stone hammerheads, called grooved mauls, are common ground stone artifacts found in North Dakota. Grooved mauls are hafted percussion tools, and the maul head represents the stone part of the tool. In July 2021, a landowner donated a uniquely shaped grooved maul to the State Historical Society’s Archaeology and Historic Preservation Department. This grooved maul measures 8.6 inches (22 cm) in length, 10.6 inches (27 cm) at its widest circumference, and weighs 7 pounds (3.2 kg). According to the donor, the maul head was found in Stutsman County, south of Plow Lake.

The longitudinally arranged channels, or flutes, pecked into the surface of the maul and extending from the handle groove to the working end make this one of the most unique mauls ever found in North Dakota. The handle groove goes almost all the way around the maul. The parallel flutes are common to grooved axes, and they are less likely to occur with grooved mauls.

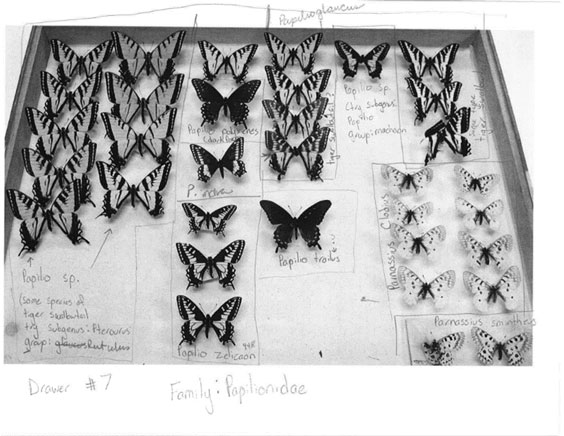

A grooved maul with additional parallel fluting pecked into the surface from Stutsman County. SHSND AHP Educational Collection

Grooved maul heads vary in size, weight, and grooving pattern. For example, based on the grooving pattern, maul heads can be classified as either full grooved or three-quarter grooved. While a full-grooved maul head has a groove that completely encircles the object’s circumference, a three-quarter grooved maul head has a groove that encircles three-fourths of the circumference. Grooved maul heads were usually made on a selected cobble that already possessed a spherical or ovoid shape. Grooved maul heads were mostly made of granite, basalt, and other igneous and metamorphic rocks. They were hafted with either split stick or twisted rawhide. Handles were attached to the pecked groove and often placed closer to the poll end or near the midpoint of the maul.

Grooved mauls were essentially the sledgehammers of their day; they could be used for any activity requiring impact force (Adams 2002; Morrow 2016, 324). They were used for food preparation tasks, including breaking bison bones to extract marrow, as well as pounding dried meats and chokecherries (Fedyniak and Giering 2016). Additionally, they could be used for hammering stakes into the ground, driving wedges through wood, and even killing small animals (Adams 2014). According to Highsmith (1985, 69), the rarity of fluted ground stone artifacts may suggest their special function in a non-utilitarian context. Fedyniak and Giering (2016, 77) have described the use of stone mauls in healing ceremonies. Experimental studies and use-wear analyses can provide insights regarding the possible functions of grooved mauls.

Distal, left, and proximal ends of the grooved maul. Evidence of use-wear is more visible in the working, battered distal end of the maul head. SHSND AHP Educational Collection

Most grooved mauls are found on the surface of archaeological sites and often are collected by landowners and avocational collectors. Very few grooved mauls are recovered from secure archaeological contexts. Most of our grooved maul artifacts were acquired through gifts and donations, and we have little-to-no provenance information for these collections.

Moreover, grooved mauls could be used/reused for a longer time—hundreds and possibly thousands of years—and this makes it difficult to accurately date them (Fedyniak and Giering 2016). In the case of the maul head from Stutsman County, we do not know its archaeological context. In general, grooved mauls appear to be associated with the later part of the Native American occupation of North Dakota, but they could be also found in the earliest time periods; a temporal range of Early Woodland to Historic times seems most likely (Deaver, Deaver, and Bergstrom 1989; Morrow 2016, 324). For example, a grooved maul recovered from the Bull Ring site (32ME166) may date back to the Early Plains Woodland Tradition (circa 400 B.C. to 100 B.C. in North Dakota). On the other hand, South Cannonball (32SI19) grooved mauls temporally may represent the Extended Middle Missouri Plains Village occupation, dating roughly from A.D. 1200 to 1400 (Griffin 1984, 95; Johnson 2007). Grooved mauls were recovered from controlled excavations at the South Cannonball site, where 15 massive grooved mauls were found (Griffin 1984, 59). The presence of a large number of grooved mauls in the northern Plains may indicate the importance of this artifact in the day-to-day activities of the Native people.

Examples of grooved maul heads from South Cannonball. SHSND AHP 92.2.720, 3590, 4689, 6393, 6453, and 6770

Replicas of full-grooved hafted mauls. A handle creates more leverage and force. SHSND AHP Educational Collection

Size comparison of the grooved maul head from Stutsman County, right, with one of the replicas. SHSND AHP Educational Collection

References

Adams, Jenny L. 2014. Ground stone analysis: A Technological Approach. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Deaver, Ken, Sherri Deaver, and Mike Bergstrom. 1989. Onion Ring, 32ME166, A Tipi Ring Site in Central North Dakota. Report prepared for The Coteau Properties Company, Bismarck, ND.

Fedyniak, K., and K.L. Giering. 2016. “More Than Meat: Residue Analysis Results of Mauls in Alberta.” Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper 36: 77-85.

Griffin, D.E. 1984. “South Cannonball (32SI19): Extended Middle Missouri Village in Southern North Dakota.” Submitted in fulfillment of Contract CX 1200-7-3554, Rocky Mountain Region National Park Service. Colombia, MO: Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri.

Highsmith, G.V. 1985. The Fluted Axe. Amherst, WI: Palmer.

Johnson, Craig M. 2007. A Chronology of Middle Missouri Plains Village Sites. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, no. 47. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

Morrow, Toby A. 2016. Stone Tools of Minnesota. Anamosa, IA: Wapsi Valley Archaeology, Inc., https://mn.gov/admin/assets/stone-tools-of-minnesota-part1_tcm36-247478.pdf