A Visit to Burlington Homes: A Plan for Rural Sustenance

This small barn still features typical elements from its construction in 1936: the sliding barn door and the small, centered loft door with a fixed, four-pane window.

In 1934 families of lignite coal miners west of Minot at Burlington faced a bleak future. The Depression was grinding into its fourth year, employment in the coal mines was slack, and people were losing hope. The lignite coal mines never offered much employment, just a few months in the winter. Now the local lignite mines faced stiff competition from out-of-state coal mines that had harder coal that burned hotter, offered at about the cost of local lignite coal thanks to cheaper railroad transportation.1

Similar grim conditions were everywhere at that time, and the federal solution was to funnel funds to states, as state and local governments, as well as private and religious charities, had traditionally supported people facing hard times. A nonprofit group, the North Dakota Rural Rehabilitation Corporation (NDRRC), received about $100,000 to solve the destitute conditions of about 40 families by providing irrigated land, a house, a small barn, a henhouse, and a privy.

The NDRRC incorporated in 1934, and by late 1935 had purchased 640 acres for irrigable land, pasture, and home sites. It planned a dam on the Des Lacs River to provide gravity-fed irrigation water, and contracted to build about 35 sets comprising a house, barn, henhouse, and privy.2 It appears that five families left the area or otherwise did not participate in the program.

The general idea was that the families would work cooperatively to market cash crops such as strawberries, raspberries, and seed carrots to local outlets near Minot. They could also raise hens and gather eggs, and the small barn could easily house a cow and calf as well as agricultural supplies and tools. They rented to own and paid $25 to $35 a month for a few acres of land, shared pasturage, and the house, barn, henhouse, and privy. By the early 1960s the project had reclaimed the $100,000 through rent, 40 percent of the hay crop, and 25 percent of the grain crops.3 The Burlington Homes Project was closely connected to Judge A. M. Christenson, who donated many hours to advance the project’s success.

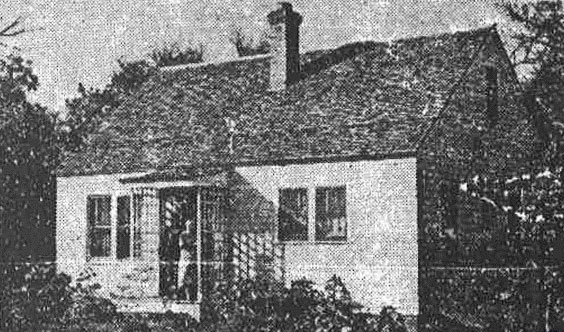

This Minimal Tradition home has a basement and five rooms, including space for two bedrooms upstairs. The brick chimney, slightly offset door, sets of windows flanking the front door, two windows down, and one window in the apex of the gable end are features found in the Burlington Homes houses. Originally the homes had red cedar shingles, a small shed roof above the front door, and were heated with coal furnaces. From Burlington Centennial, p. 94.

A sturdy but small henhouse with a people door on the gable end. The tiny ventilator and ridge cap are original features of the henhouses.

The architectural firm Van Horn and Ritterbush provided specifications for these small buildings, which included high-quality materials such as fir structural members and red cedar siding, and conservative building practices like 12-inch on-center spacing for the ceiling joists in the small barns. The applicant families apparently had some say in the house design, since some have elevated basements, and some had rough-in plumbing initially while others did not.

The electrician was instructed to provide rough-in electrical wiring and detailed instructions to homeowners on how to wire light fixtures and electrical switches.4 One house, recently remodeled, had the outdoor water pump just outside the front door, which provided all the water for domestic purposes, at least initially. The specifications mentioned that the applicant families were to provide their own water well and trenching for the concrete privy vault.

Today the 1.5-story Minimal Traditional homes, small barns, henhouses, and at least one privy still dot the landscape along North and South Project Road just west of Burlington. Many of the homes have been remodeled, but the barns and henhouses are a tangible reminder of difficult times and creative solutions to improve a whole community. In the 1950s some of the lots were offered on a rent-to-own basis to veterans with disabilities, and eventually all of them transferred to private ownership.

Well-preserved barn at TC Landscaping in Burlington, still useful after more than 60 years.

1 Burlington Centennial, 1883–1983 (self-pub., 1983), 92; “A Brief History: National Association of Rural Rehabilitation Corporations,” accessed Sept. 12, 2019, http://www.ruralrehab.org/briefhistory.html.

2 Burlington Centennial, 90; Steven Martens, “Federal Relief Construction in North Dakota 1931–1945,” accessed Sept. 12, 2019, https://www.history.nd.gov/hp/historiccontexts.html.

3 Burlington Centennial, 90. For further background information, see Gudmund Leonard Dalstad, History of the North Dakota Rural Rehabilitation Corporation (Bismarck, ND: self-pub., 1996).

4 Specifications for the Burlington Homes Project, 3rd group of buildings, Van Horn Ritterbush Company Collection, box 6, file 47000107, State Archives, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.