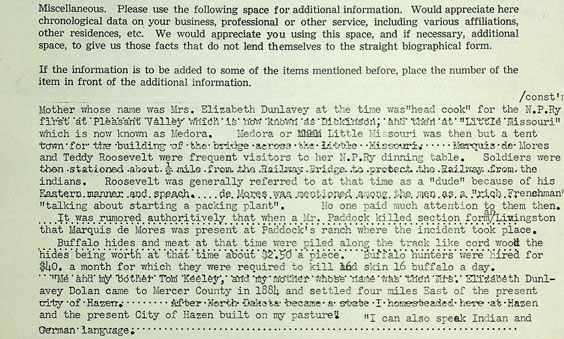

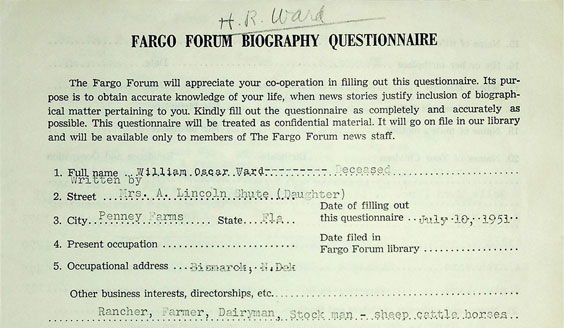

This week 109 years ago, a variety of forces joined together for what promised to be the “greatest publicity ever secured by any commonwealth since Noah built the ark.” In a proclamation, Gov. Louis Hanna declared Nov. 14-20, 1915, “North Dakota Appreciation Week.” Dreamed up by the North Dakota Press Association, the booster effort was aimed at encouraging migration to a state the Bismarck Daily Tribune breathlessly dubbed “an empire in the making.”

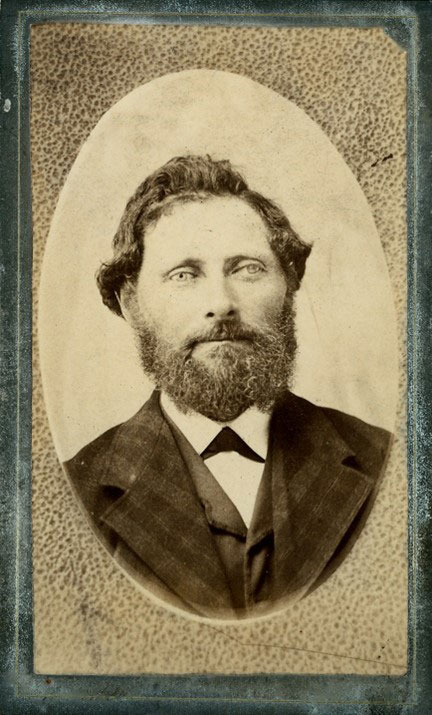

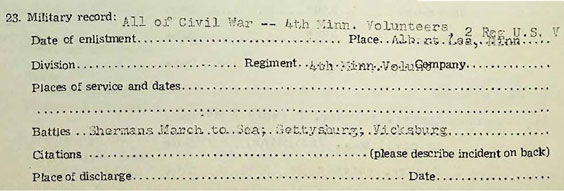

The colorful Edgar Richter, head of the North Dakota Press Association, was a tireless advocate for the state. Bismarck Daily Tribune, Nov. 18, 1915, p. 1

Every “loyal North Dakotan” was to do their part. Residents were urged to write letters to friends elsewhere praising the advantages of life here. Farmers were to pen testimonials on the state’s agricultural yield. Schools were to impress upon students the benefits that awaited “industrious, thrifty, and upright citizens” of North Dakota, with gold prizes offered to those who submitted the best essays extolling its appeal.

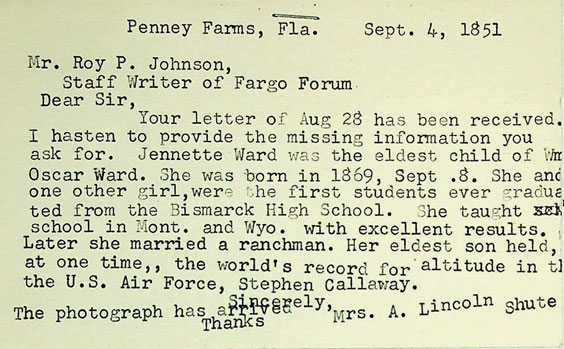

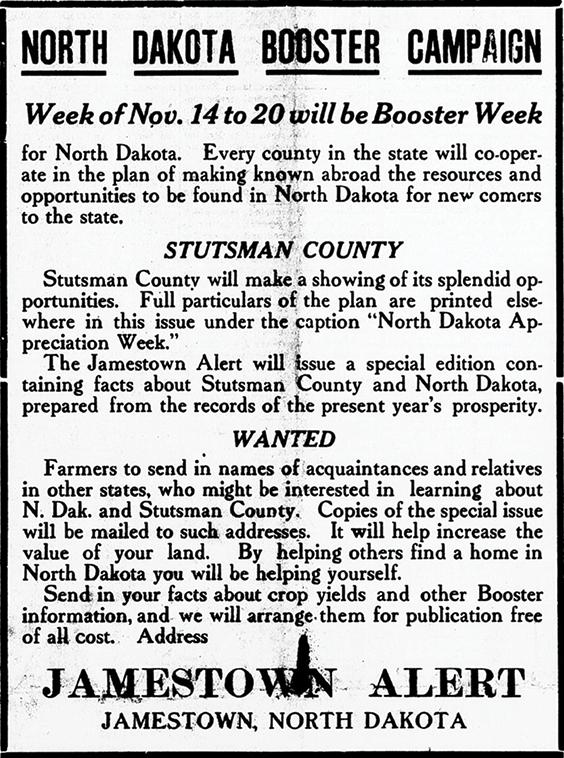

Jamestown Weekly Alert, Nov. 4, 1915, p. 1

Amid dispatches from the Great War raging in Europe and ads for upcoming Thanksgiving sales, North Dakotans expressed gratitude for their good fortune. That week, “the gospel of North Dakota” was preached during appreciation church services. (Sample grab: “Lord, thou hast dealt favorable unto the Land.”) Newspapers published booster editions bursting with eye-popping stats on North Dakota’s abundant resources and featuring laudatory poetry. Commercial clubs held meetings and dinners enumerating the state’s opportunities.

Left: Grand Forks Daily Herald, Nov. 8, 1915, p. 6

Right: Washburn Leader, Nov. 19, 1915, p. 1

I first learned about ND Appreciation Week while doing research for an upcoming State Museum exhibition to mark the nation’s 250th birthday. Among the planned exhibit themes is the many ways over the years that North Dakota has been promoted to outsiders and the wider world. It came as no surprise to read that the booster week was backed by major railroad presidents, who presumably saw an opening to increase customer numbers and land sales along their lines under the guise of fostering “state patriotism.” As the Devils Lake World and Inter-Ocean noted in an editorial, “Convince yourself of her greatness, then tell others. Each of us is a factor in the upbuilding of North Dakota, therefore each must do his or her part.” Or to put it more bluntly, as Valley City’s Weekly-Times Record admonished, “The proper thing for every North Dakotan to do is buck up and boost.”

Fresh off their success at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (otherwise known as the 1915 World’s Fair), where a display in the North Dakota building showcased an impressive corn tower, Flickertail State leaders were eager to seize the momentum in the push for more settlers and economic development. The impresario directing this stunt was Edgar L. Richter, editor of the Larimore Pioneer and president of the press association, not to mention the brains behind Baked Potato Day at the exposition that year (where Larimore tubers were served to thousands of hungry fairgoers). Richter, an indefatigable champion of the state, had grand plans for North Dakota, including turning Larimore into a “winter resort” for “Fifth Avenue millionaires.”

Boasting an elaborate corn tower adorned with slogans such as “North Dakota Enlightening the World” and “State of Opportunity,” the North Dakota building at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco evoked the over-the-top promotional stunts of the era. SHSND SA E0409-00001

Richter’s work paid off, with the appreciation week heralded a universal success. In its aftermath, the Christian Science Monitor asserted that “the commonwealth now feels happier, goes about its business with more confidence, and has more assets in its social treasury.”

But the state’s demand for more people was hardly unproblematic nor without its contradictions.

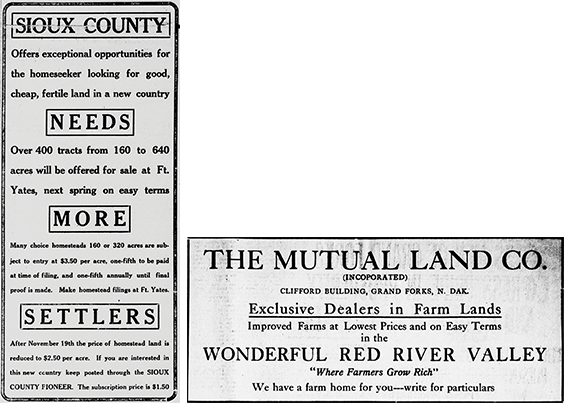

Five years before, Hanna, then a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, had introduced a bill that became law opening up the sale of “surplus” Fort Berthold Indian Reservation land to non-Indians, a violation of 19th century treaties. Strikingly, as papers in fall 1915 pushed for “more settlers,” their pages frequently highlighted opportunities for potential homesteaders to acquire Fort Berthold and Standing Rock Indian reservation lands, further breaking up Native American holdings in favor of European settlement.

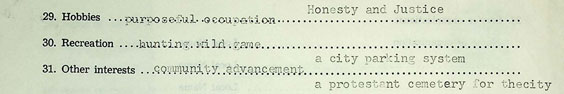

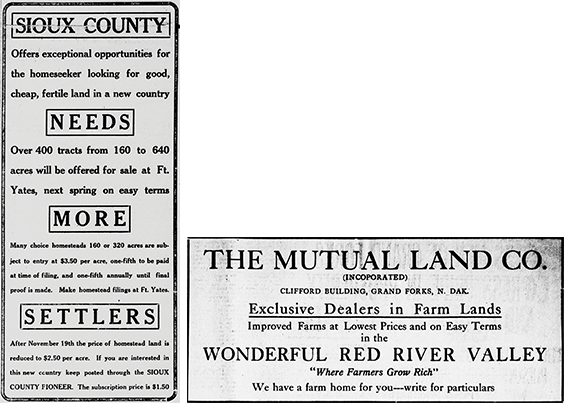

During the booster week, newspapers ran enticing ads meant to lure settlers to North Dakota. Sioux County Pioneer, Nov. 19, 1915, p. 1, Grand Forks Daily Herald, Nov. 18, 1915, p. 3

Though much has changed since those days, North Dakota’s need for people has remained constant, with only 30 available workers for every 100 open jobs. Like historical public relations efforts to proclaim the state’s desirability, current outreach campaigns, such as “Find the Good Life in North Dakota,” focus on the happiness and opportunities to be had here, albeit in more measured tones. Meanwhile, an Office of Legal Immigration was recently created to recruit foreign labor and address workforce challenges, some 90 years after the demise of the first state immigration department. As current boosters seek to enhance North Dakota’s standing on the global stage, they’d do well to steal a page from the playbook of the Grand Forks Daily Herald, which on Nov. 18, 1915, assured readers: “There is no more healthy or desirable dwelling place under the skies.”