The Impact of Research

Every month, we receive hundreds of historical and genealogical requests in the State Archives – in fact, more than 6,000 each year. However, only three of us deal with the majority of this inflow. Jim Davis, head of reference staff, started working here when the North Dakota Heritage Center was built in 1981. He was originally hired to unpack collections moved from the Liberty Memorial Building, where the State Historical Society used to be, to the new Archives wing. Luckily for us, he stayed. Greg Wysk has been here for just over 13 years. Greg is really involved with the family history side of research and has presented at quite a few family research workshops on the subject. I am the third and have been here for almost seven years.

Remember this image from my explanation of what an Archives is and holds from my first post? We have long been the official state repository for newspapers, and though the collection is not complete for many of those earlier years, we have most issues from most areas. Older ones are on microfilm.

We all deal with different types of requests. Some are straightforward, but some are not. Some stick with you. I’ve helped a woman create a shadow box with artifacts about her family member’s sporty past; helped a couple find the location of where their relative was buried so they could place a tombstone there; helped a man find his step-siblings through an obituary search; and just recently, helped a researcher who was looking for a divorce record determine that the couple in question never actually divorced.

One of the most memorable requests, however, was one that Jim and I worked on together. The researcher involved was interested in a tragedy that had occurred in New Salem in the early 1950s concerning a man who had shot and killed the chief of police of New Salem. He had tried to get information on the trial, but was told repeatedly that the records were closed. When he came to us at the Archives, we turned to the local newspapers, a public source, and found his answer.

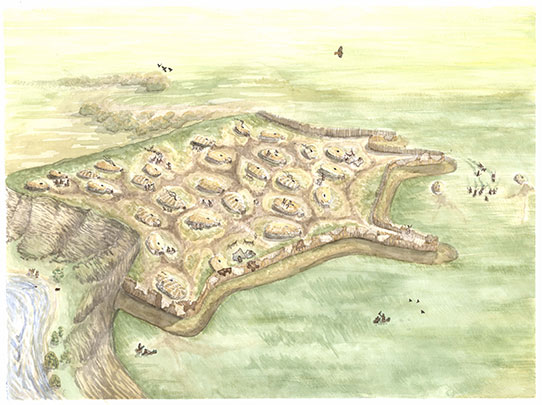

The Chief of Police who was shot is shown in this paper from New Salem.

As it turns out, the man charged with murder had been passing through the area with his wife and kids, looking for work. The kids had bought some pop at a local soda shop. When they were charged a penny’s tax on the pop, they protested and departed; then their father came in to protest as well. As the situation escalated, the chief of police was called. He picked the man up—but then the man turned on him, shot him, hijacked a car, and took his family down toward the border of South Dakota before he was finally caught.

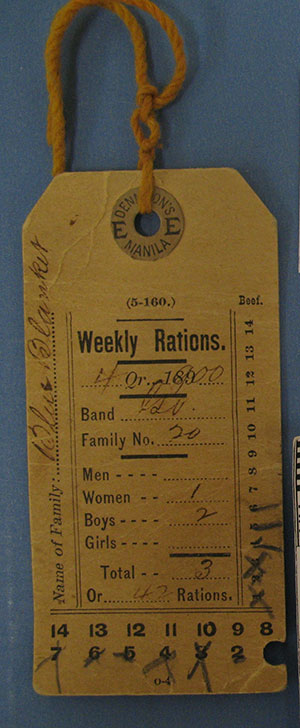

This was big news, and many newspapers in the area reported on the tragedy. In this image, the owner of the café points to bullet holes that were shot through her front window during the incident.

The researcher looking into this case was a family member of the accused party, and he wanted to find out what had happened. Knowing this made me uneasy. What do you do when you discover information that shows someone’s relative to be a murderer? I was still pretty new at the time, but even then, I had seen what people experience when they find out anything about their relations. It can be very emotional working here. I’ve seen people cry with joy at finding a solitary picture, and I’ve seen people walk away in total surprise and even disbelief when they’ve unearthed someone’s checkered past.

However, as Jim reminded me when I expressed this, nobody can change the past. We can only find what our records show us and provide that information.

Luckily, in this case, there was no need for unease. The researcher was elated to learn what we had found and contacted us several times more for follow-ups and additional information.

I was talking to a woman recently about her own request, and when I told her that I finished it, she said, excitedly, “What a great job. You help people find their past. You help people find themselves.”

Not every research request, historical or genealogical, is easy to deal with, and every one comes in with its own set of challenges and constraints—but then again, every bit whops an impact.