You Got Your Science In My History!

Do you remember the old Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup commercials? A couple of people bump into each other, mingling their chocolate and peanut butter snacks? Initially they are irritated with each other, but then they discovered the tasty goodness of combining the two treats. I think of those old ads every time I hear people asking why history museums need to add science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) to their regular programming. STEM is more than a trend or a buzzword. What seems to really be new about the STEM concept is the realization that we need to do more to engage students. This includes developing new ways of getting excited about subjects that are vital for a well-rounded education, and meet the needs of our modern workforce. This seemingly new push to include STEM curriculum into museum programming can initially cause some frustration. However, I like to think of it as my job to help people see the delightful new things we can now enjoy together.

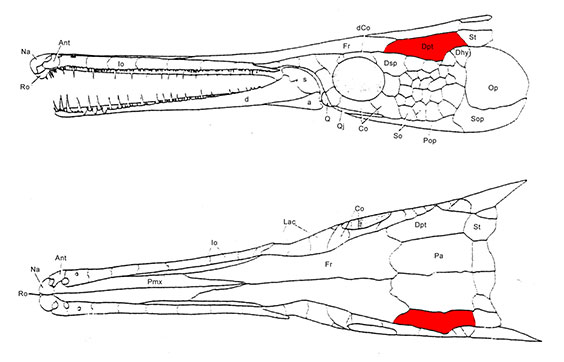

Hesperornis and Xiphactinus are part of a nice science buffet in the new galleries.

So what does all of this have to do with history, and why does the State Historical Society of North Dakota care about STEM? Well, I’d like to challenge you to take history out of the science classroom or try to take science out of the history museum. I don’t think it can really be done without sacrificing something special and leaving us with substandard subject matter. Using science as an example, most textbooks have sidebars to explain why people such as Marie Curie and Albert Einstein are important to the field. Science classes also usually dig into how the field has changed and developed over time and how new research has added to or challenged previous understandings. That all speaks to the importance of using historical thought to help develop a well-rounded science class. In turn, we can take our students into the new Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples at the North Dakota Heritage Center and look at all the ways to think about STEM in a museum context.

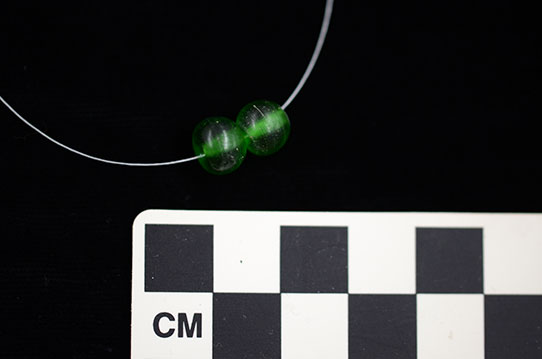

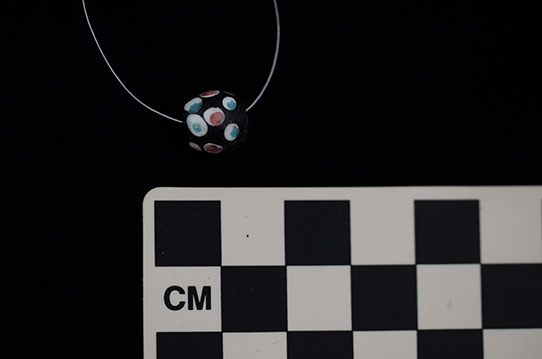

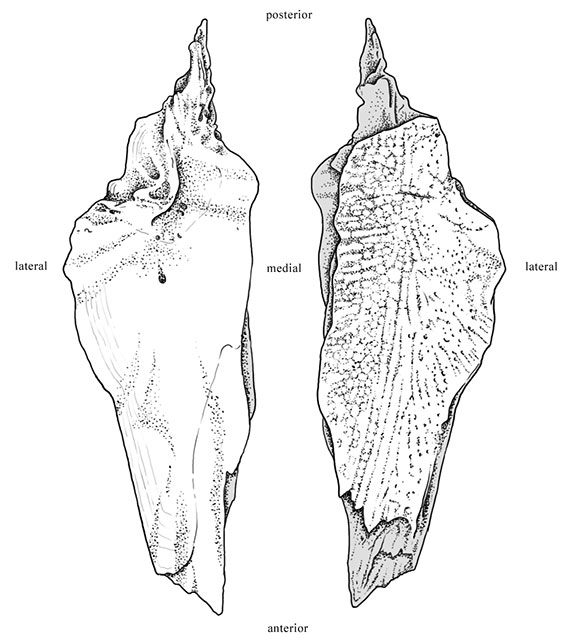

Left: A stone tool demonstrates the technological skill of early peoples.

Right: Tipis and earthlodges are perfectly engineered for living on the prairie landscape.

There is the technology involved in flintknapping to make stone tools. There is science involved in brain-tanning animal hides. There is math involved in figuring out how much food needs to be stored to get your community through a hard winter. We even have the engineering involved in building a home on the prairie.

This exhibit in a grain bin is a great showcase for featuring the rich agricultural history of our state.

Music, literature, and art are also all represented in the new galleries. Need writing prompts for students? Our galleries are full of them. Interested in getting kids to think about nutrition for a health class? Spend some time in our galleries learning about traditional foodways of the Native Americans and immigrants who have lived here. Need an opportunity to connect urban students to where their food comes from? We’ve got you covered.

No matter what you are learning about, we have objects and artifacts that can help make a topic relevant for students. Even if you don’t think your topic is history-related, the history is probably all over it, making for a great intellectual treat.