Adventures in Archaeology Collections: Squash

Pumpkins seem to be everywhere this time of year — jack-o’-lanterns in October, pies in November, and flavored lattes in coffee shops all the way through the new year. What we call pumpkins in the United States are squash. And while the current pumpkin-flavored options might be new and trendy, squash are not new to North Dakota.

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people living along the Missouri River have grown squash for a very long time. The northern plains are not the easiest place to grow things — winters are long and cold while summers are usually short, hot, and dry. But Native gardeners developed and grew squash that survive in this climate. Traditional kinds of squash come in many shapes, sizes, and colors.

Replicas of traditional varieties of squashes grown on the northern plains, left to right: Omaha pumpkin, Arikara winter squash, Mandan-Arikara green and white squash (SHSND 841.2, 37, 22). These are on exhibit in the State Museum’s Innovation Gallery.

Many of these squashes are still grown today, like these Arikara winter squashes.

A winter variety of Arikara squash I grew in my garden this year

Traditionally, women grew squash in large gardens. Squash was an important food crop along with corn, beans, and sunflowers.

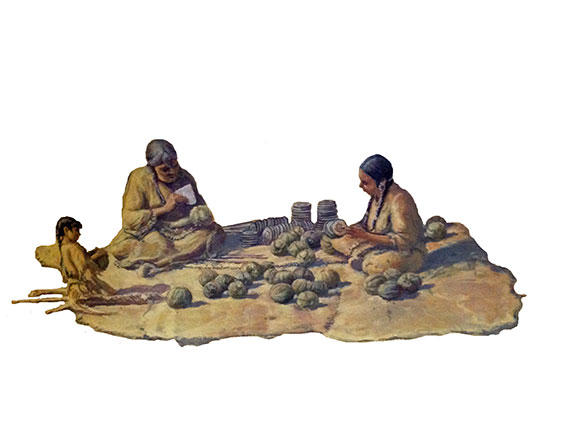

Two women and a child processing squash together — detail from the cyclorama of Double Ditch Indian Village in the State Museum’s Innovation Gallery. (Original art by Rob Evans)

Some squash was eaten fresh. Dried squash was used in soups, stews, and other dishes. Squash was cooked many ways — boiled or steamed in a pot, roasted in the ashes of a fire, or boiled with other ingredients like squash blossoms, fat, beans, or cornmeal. Squash seeds could be boiled, parched, or roasted. Squash blossoms were also used in dishes either fresh or dried.

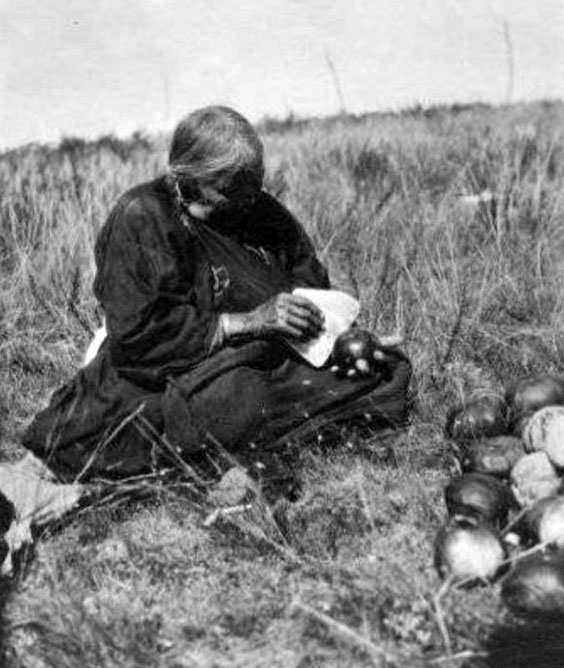

A lot of squash was prepared for winter food. In these photos, Owl Woman shows how squash was cut and prepared for the winter.

Owl Woman demonstrates four steps for squash preparation. First, slice the squash into rings using a squash knife. (Photo by Gilbert Wilson, SHSND SA 0086-0332)

Second, after the squash are sliced, began stringing the slices on a spit. (Photo by Gilbert Wilson, SHSND SA 0086-0340)

Third, finish stringing the squash slices. (Photo by Gilbert Wilson, SHSND SA 0086-0339)

Finally, hang the squashes on a rack to dry. (Photo by Gilbert Wilson, SHSND SA 0086-0326)

The squashes were sliced with squash knives typically made from bison scapulae (shoulder blades).

A bison scapula squash knife fragment from Larson Village (32BL9). (SHSND AHP 2013A.19, F26, south half).

Squash were used for other purposes too. Some squash seeds were saved to plant the next year.

Squash seeds from Like-A-Fishhook Village (32ML2). (SHSND AHP 12003.258)

Squash leaves could be used as disposable spoons. At harvest time young girls would sometimes pick out squashes to use as dolls.