Hidden in the Badlands: 5 Surprises at the Chateau de Morès

Call me Madame. Actually, you can call me Anna; we reserve the title “Madame” for Medora von Hoffman, the first lady of the Chateau de Morès. She and her husband the Marquis de Morès, Antoine de Vallambrosa, lived here 136 years ago. A lot has changed over the decades, but the Chateau itself has remained steady, guarding its secrets well.

What secrets? I am so glad you asked! At first glance, the Chateau seems like a lovely home tucked on a butte beside the Little Missouri River. The Marquis and Madame strove to be on the cusp of national innovation, and their opulent style is clear. However, throughout the house are hidden messages about their lives that only eagle-eyed guests can find.

Keeping with Madame’s spirit of hospitality, I invite you to come along for a sneak peek at my top five hidden surprises at the Chateau!

1. Fresh Air

On hot summer days, Madame could be found in her office planning anything from menus to hunting trips. But when the heat rose, she needed fresh air. Because of social boundaries, a lady could not simply open her door to allow the breeze to flow. Instead, she had to protect her modesty. Coming to the rescue, the Marquis had small windows built at the top of Madame’s office and bedroom walls that allowed fresh air into her rooms without compromising her privacy.

The small windows at the top of the frame, shown here from the Chateau porch, lead to Madame’s bedroom and office.

2. Talking in Code

Madame and the Marquis tried to embrace the western frontier while keeping pace with eastern society. To that end, the main level of the house has several distinct areas: the dining and living rooms, the homeowners’ private quarters, and servants’ areas. Each room is connected by a hallway that circles the entire first floor. Each door in the hall is equipped with faux-stained glass that allows light to shine through while maintaining privacy. And, these doors talked in code. If the doors were open, servants knew they were welcome to pass through. If closed, they should refrain from entering.

View of the servants’ corridor in the dining room. This door is shut, so you know what that means . . . no servants can pass through!

3. Baby, It’s Cold Outside

This fireplace is impressive. Measuring five feet deep, it could put out some heat on a cold night. Did you know this is the only fireplace in the entire Chateau? Based on an unfortunate claim, the Marquis believed the climate in the Badlands was mild and one fireplace would keep the cold at bay. This was wrong, but some years the family still managed to stay as late as December before leaving to enjoy a milder European winter.

This fireplace was the centerpiece for guests in the Chateau who gathered in the living room for entertainment. Can’t you imagine settling on the settee and reading a good book?

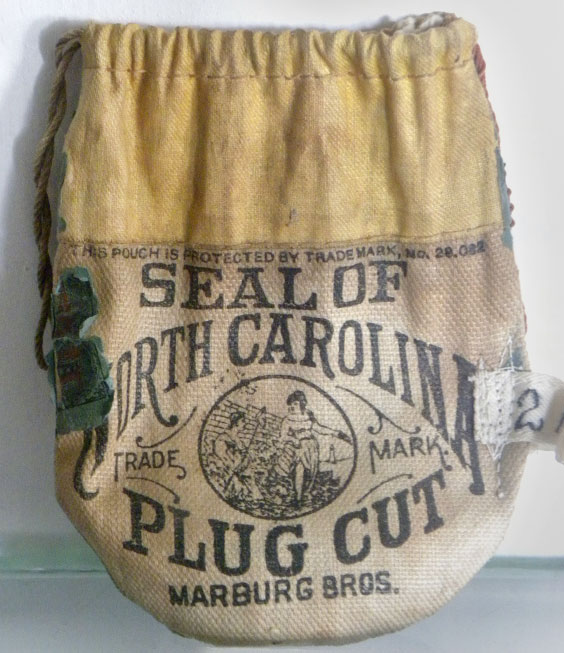

4. Richie Rich

My favorite clue, stashed among the wares of the hunting room, is one bag of tobacco. This seemingly ordinary purchase is a huge hint about the Marquis! In the 19th century, tobacco was just beginning to gain in mass popularity, and southern states like North Carolina had already proven to produce some of the highest quality plug tobacco in the nation. The Marquis used his wealth to ship it across the continent to North Dakota, showing just how much he was willing to spend on luxuries.

Originally from Germany, the Marburg brothers moved to North Carolina and went into business with J.B. Duke and the American Tobacco Company. If the name “Duke” sounds familiar, Duke University was named after J.B.’s father.

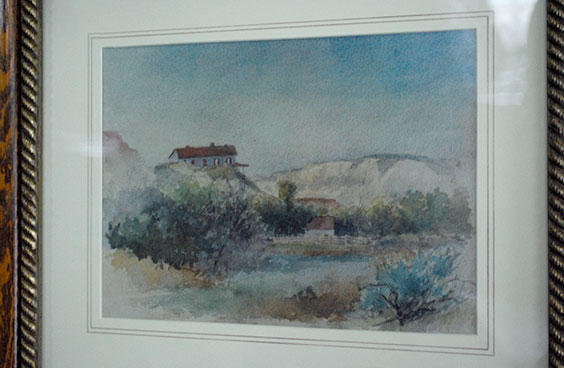

5. Lost in Time

Several decades ago, a collection of beautiful watercolor paintings were gifted to the State Historical Society. The artist was none other than Madame herself. Among her impressions of the Badlands and international landscapes was one small painting of the Chateau. This is the most valuable to us, because it is the only known image of the Chateau completed in color. Thanks to Madame we now know the authentic colors to paint the house.

Today, the Chateau is painted to look like Madame’s watercolor version.

The next time you visit the Chateau, be sure to keep an eye out for more clues! You never know what history lies hidden in plain sight.