From Minnesota to Dakota to the Civil War: The Kenney Family Letters

One of the joys of being an archivist is the opportunity to work with collections that relate to your professional historical passion. In my case, it is military history (specifically the American Civil War) that excites me. While North Dakota is on the fringe in relation to America’s bloodiest conflict, we do have a connection to the conflict and the State Archives has several collections containing materials about individuals’ experiences.

The Kenney Family Papers, a recent addition to our collections, highlights the service of two brothers, Joseph Edwin and George W. Kenney, who served in Company D, Fourth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Joseph, 31, enlisted on Oct. 8, 1861, while George, 21, enlisted Oct. 10, 1861. Organized in St. Cloud, Company D mustered into service on Oct. 10, 1861, and proceeded to Fort Abercrombie, Dakota Territory for garrison duty.1

From late December 1861 until February 1862, the brothers wrote at least five letters home to their family. In a letter from Fort Abercrombie written on Dec. 22, 1861, the brothers discussed the cold weather and snow, but noted that it was nice. Their big complaint was that they had written five letters home at that point and only received one letter in reply. In their other letters from Abercrombie, the brothers discussed the weather, their health, and news from home.2

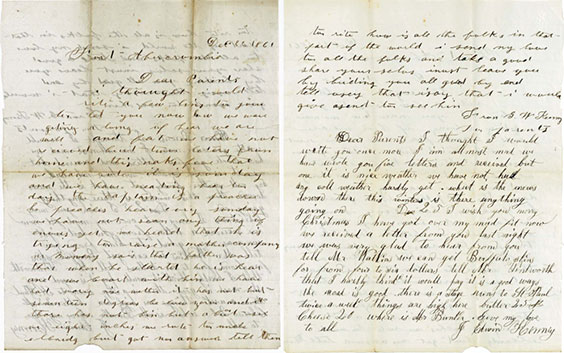

What is fascinating is the difference in the writing styles between the two men. George’s handwriting and overall style are less refined than Joseph’s, as George’s portions of the letters are full of spelling and grammatical errors, shown in the images. This leads to speculation as to a difference in education levels between the two, especially as Joseph was promoted to corporal.

Notice the difference in the handwriting of George (left) and Joseph (right). Item # 11371-00001-1 (left) and 11371-0000-2 (right).

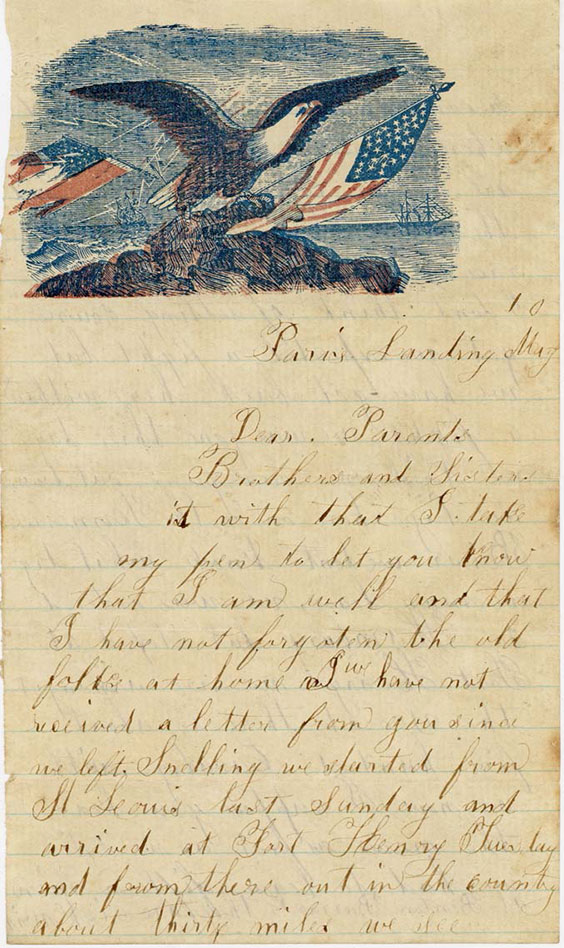

Some of the letters in the collection incorporate artistic letterhead, which was a feature of some letters home from Civil War soldiers. This artwork usually invokes patriotic imagery or images of home. One good example is the letter from Joseph to his parents and siblings on May 10, 1862 from Paris Landing in Tennessee. In the letter, he noted traveling from St. Louis, stopping at Fort Henry, and traveling down the Tennessee River. The letter ended abruptly, noting several sick men were being left at Benton Barracks in St. Louis.3 Note the eagle in the upper left of the image of that letter below.

Some letters from war were written on paper containing letterhead with patriotic images, like the eagle with its beak towards the American flag and away from the Confederate flag. Item #11371-00007-1.

In one letter home, Joseph shares the circumstances of his brother George’s death in Mississippi from disease in late May 1862. On Aug. 29, he wrote, “you want to know the particulars of the death of dear George he died in the morning and was burried [sic] in the evening he died easy I was in the same tent we had pretty good beds we have a good Chaplain I like the Captain, you spoke about his pay I cannot get any untill [sic] there is a final settlement and then we can get his bounty.”4

In addition to the letters home from the brothers, the collection includes a couple other letters from people who knew the two men and bring their stories to a sad conclusion. One letter, dated June 12, 1863, from Lavinia (Vinia) Lambert of Langola, Minnesota, to the brothers’ mother provided some details surrounding their fates. Vinia’s father served in Company D with them and wrote home about them. These letters tell us that Vinia’s father cared for George to the end of his illness. She noted that he experienced delirium as his mind wandered to thoughts of family and friends back home. She also wrote of her father being present when Joseph was killed at Vicksburg, Mississippi, on the evening of May 22, 1863, being “shot through the head.”5

The final letter in the collection is from Edward Dowling to Joseph’s and George’s father. Dowling was in the same company as the brothers and discussed the circumstances surrounding Joseph’s death in battle. This was a common occurrence for soldiers to write the families of fallen comrades to explain circumstances of their loved ones’ deaths. He wrote, “I think that he was as Brave a Soldier as ever went into a Battle” and noted that he died in a charge and that a truce was called three days after to allow burial of his body. Dowling mentioned that Joseph’s grave was unknown, owing to another burial being close by and unmarked.

One item Dowling noted in his letter to Kenney’s father was the extent of his personal effects, especially his clothing. Joseph only had “two shirts and a pair of socks,” having thrown the rest away along his marches, including his knapsack, while losing his blanket in the charge that resulted in his death.6 It was quite common among Civil War soldiers to ditch cumbersome and uncomfortable equipment along the march, as they often shed their knapsacks and rolled personal belongings into blankets and slung them over their shoulders.

Thus, the story of the Kenney brothers came to a sad conclusion, as they joined the ranks of the approximately 750,000 other Americans who died in the Civil War. Their service took them from Minnesota to the prairie of Dakota Territory, and finally the deep South. One brother died from disease, which was the most common cause of death in the war, while the other died in one of the more pivotal battles of the war. Their letters are a mere snapshot of lives cut short and only a small microcosm of the Civil War. But they are a treasure to have because they link North Dakota to one of our nation’s most pivotal events.

If you are interested in the Civil War, stop into the Archives and check out the Kenney Family Papers.

1 Board of Commissioners on Publication of History of Minnesota in Civil and Indian Wars, Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865 (St. Paul, MN: Pioneer Press Company, 1890), 199, 228, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZuoLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PP8#v=onepage&q&f=fal….

2 Joseph and George Kenney to parents, December 22, 1861, Kenney Family Papers, Collection #11371, Box 1, Item 1, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.

3 Joseph Kenney to parents, May 10, 1862, Kenney Family Papers, Collection #11371, Box 1, Item 7, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.

4 Joseph Kenney to parents, December 22, 1861, Kenney Family Papers, Collection #11371, Box 1, Item 10, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.

5 Lavinia Lambert to Mrs. Kenney, June 12, 1863, Kenney Family Papers, Collection #11371, Box 1, Item 15, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.

6 Edward Dowling to Mr. Kenney, August 8, 1863, Kenney Family Papers, Collection #11371, Box 1, Item 17, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.