How to Search for Photos in the North Dakota State Archives

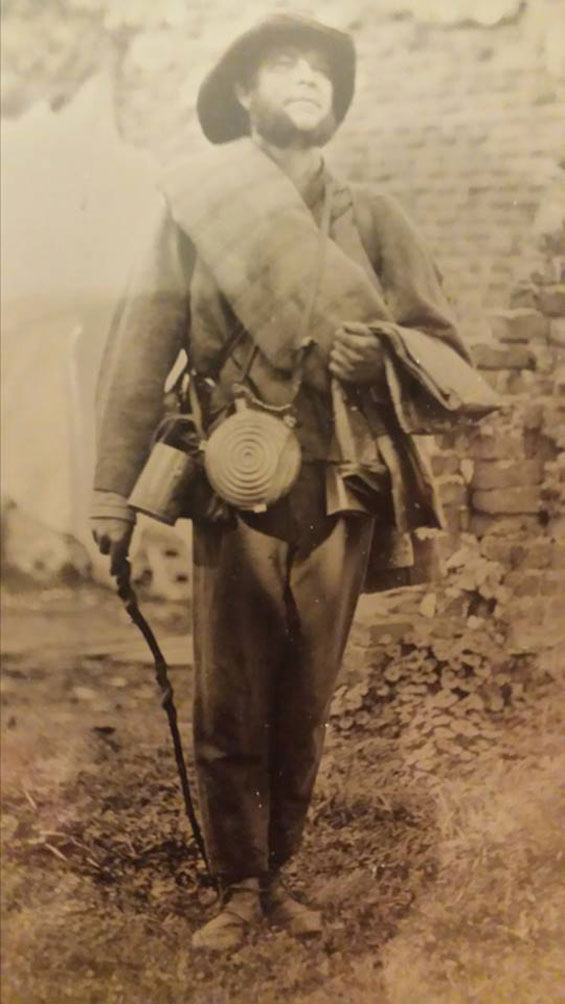

A photo is worth a thousand words, as the old saying goes. Photos can also be invaluable—especially for a researcher searching for old images of family members or historic images of places and events.

We receive many requests for photographs. We have a lot to choose from—the estimate is that our collection holds around two million photos (including glass plate negatives, prints, jpgs, tiffs, and all kinds of other materials). Not all of our images are scanned, however, and not all can be viewed on our website at this time. So how can you find an image you are searching for?

Right now, you can search in a multitude of ways. While it takes a bit of looking and a little extra work, it’s not nearly as difficult as it seems. And some of it can be done from home!

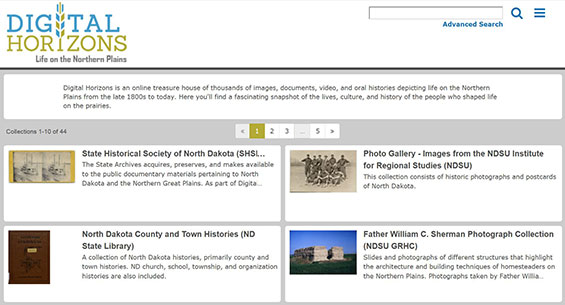

1. Digital Horizons. Digital Horizons is the easiest place to start for photo searches.

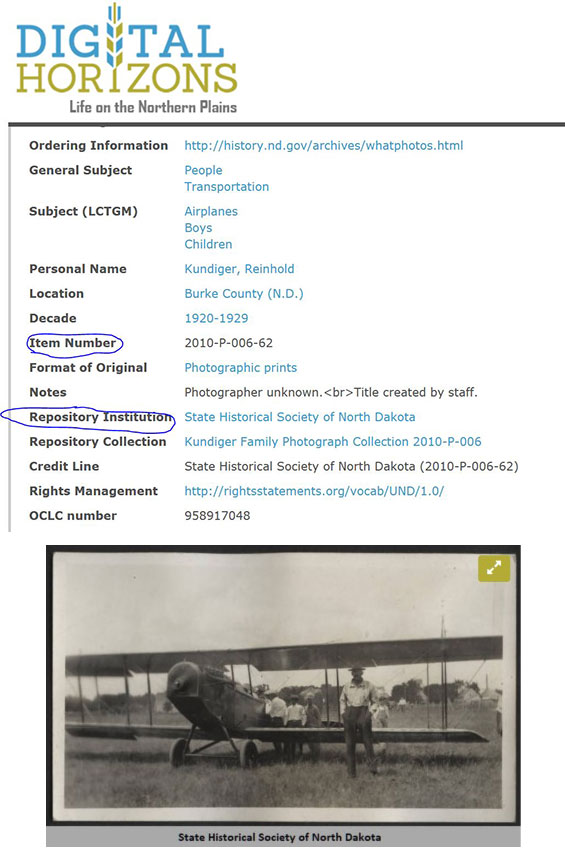

This website is a conglomeration of select images from our collections, as well as other organizations around the state, such as the Institute for Regional Studies at NDSU, the Bismarck Public Library, the North Dakota State Library, and local county historical societies. Now, I did say “select.” Not all images from every institution in the state are available here. However, it’s a great place to begin any search. You can type in a keyword search in the search bar (see Advanced Search) and can even focus on specific collections. Images are here in low resolution, but you can see them, any information we may have on them, and also can find what institution they are from, as well as the photo number.

Scrolling down on this page will show necessary information as to where this image came from. To order this image, you will need the Item Number and will want to request it from the correct repository institution.

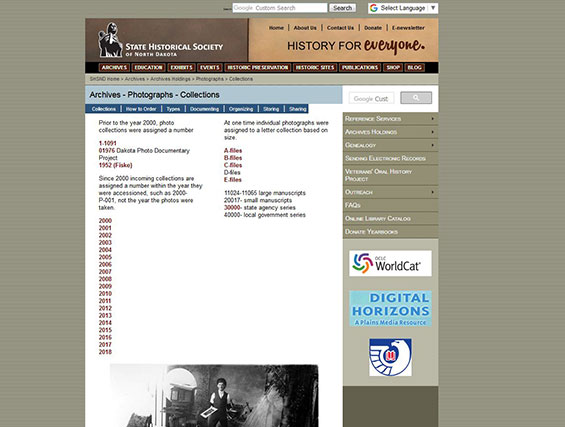

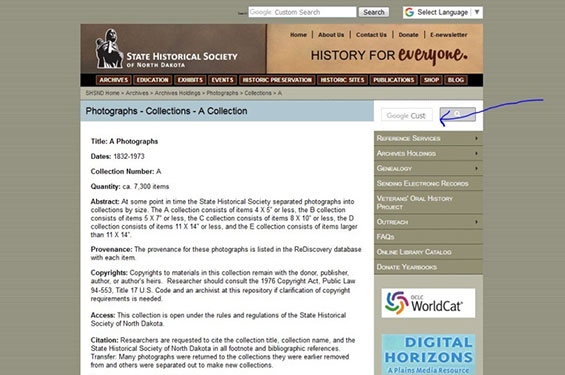

2. Photo indexes listed on our website. If you just want to know what sort of images might be available, this is a good place to start as well. You will likely not find the actual photo to look at, but most of our images are indexed and described somewhere on our website. While photo collections can exist in manuscripts and state series, and are not listed within this site, the bulk of our photos can be found in their own collections. View this at history.nd.gov/archives/photocollections.

3. Keyword searches on our website. As I noted, not all of our photos are found in photo collections. Some are listed under the finding aids of other collections. So it is indeed worth doing a keyword search throughout our website. The best ways to do this are twofold.

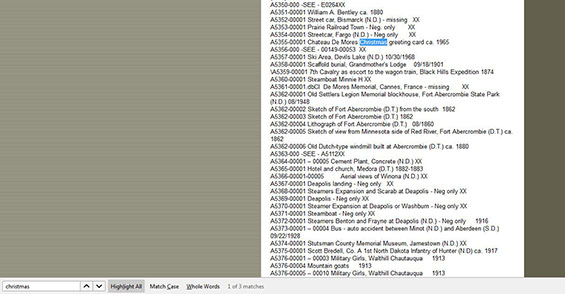

- In conjunction with searching a specific page (“control-f” on your keyboard will typically pop up the search box, and then highlight whatever string of words you are interested in).

- Do a keyword search across the website. You can type in keyword searches and do an in-site google search for topics. Go to history.nd.gov/archives and you will see two search bars. While you can use both, to search just the Archives collections, you will want to use the one on the lower right side for your search.

4. Search at the Archives. We do have a few other sources in the Archives that you can search. We have some paper files and some scanned jpgs that may not be available on Digital Horizons, but can only be viewed on a computer in our State Archives Reading Room. We also can help you with use our new database, Re:discovery, which allows staff to search for inter-agency topics. Eventually, Re:discovery will be accessible to the public as a search tool and will change how photos can be searched.

For now, these are your best options.

However, even when you are searching with these methods, there are a few things to keep in mind.

- Be succinct, and try a few key words. Being too specific (E.g., “President Theodore Roosevelt visiting North Dakota in 1902”) with your query in any of these searches will limit your results. Too general (E.g., “north dakota”) will bring in too many results. Find a happy medium. (E.g., search “Roosevelt,” “Teddy,” “President visit,” and “Roosevelt visit”).

- You can’t always see everything right away. Typically if an image is not yet scanned, I can send a small number of low-res thumbnails to individuals seeking photos, so they can see them before they order. Please remember to allow extra days for this service, as this does take time!

- Keep the photo number on hand for ordering. The photo number is how we identify and communicate about photos. It is listed on our website, on Digital Horizons, and on the photo itself. We need this information for research and orders.

I hope this helps you find the photos of your dreams! Look for my next post to see how you can use this information to order photograph scans. You will learn how these images can be used, what we expect, what we do and don’t allow, and how to place an order.