Primping and Prepping Artifacts for Exhibit

We will be opening a new temporary exhibit in the Governor’s Gallery of the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum on August 25, 2018. The exhibition, titled The Horse in North Dakota, includes about 200 artifacts and specimens from the Museum Division, Archaeology and Historic Preservation Division, the North Dakota State Fossil Collection, as well as a few items borrowed from the citizens of North Dakota.

The Museum Division staff is spending many hours of preparation on artifacts selected for the exhibit. Once artifacts are selected, the objects need to be cleaned, their conditions evaluated and reported, and object data sheets created. Each artifact that requires additional physical support must then be fitted on appropriate mannequins or mounts.

Many of the artifacts selected for The Horse in North Dakota include leather. Due to the organic nature of leather and its natural oils, a very common reaction between leather and metals occurs, especially between leather and copper. Copper in contact with leather develops a waxy, flakey, or hairy buildup that needs to be removed. Technically this accreted material is known as fatty acids stained with copper ions, but we affectionately call it “green gunk.” In order to remove the green gunk, it is gently rubbed off using thin wooden dowels, skewers, and cuticle pushers. Additionally, brushes, cotton muslin, and cotton swabs are used for cleaning. It is finished off with a swipe of ethanol.

Before and after photos of the green gunk removal from a metal ring on a saddle (14682.2). It took Melissa Thompson, Assistant Registrar, nineteen hours of work to clean all of the green gunk off the McClellen saddle.

Spew, or bloom, is a white powdery substance that appears on the surface of leather. Spew is formed when the fatty acids and oils in the leather migrate to the surface and are exposed to air. The powdery substance is easy removed with either a soft bristle brush or a cotton cloth.

Spew being removed from the strap of a saddle bag (09186) using a soft bristle brush.

Many metal objects are polished with a cream or tarnish remover while they are in use. We do not polish any of the metals in our collection for various preservation reasons. Over time, residue from the polish that was once used on the artifact turns white and can hide many of the decorative details of an artifact. Such is the case with these medallions on the sides of a bridle. The green gunk was removed using the wooden tools. Then, using distilled water and small wooden skewers, as much of the white residue was removed as possible to unveil the medallion’s detail.

Before and after removing brass tarnish residue from bridle (2007.00053.00049)

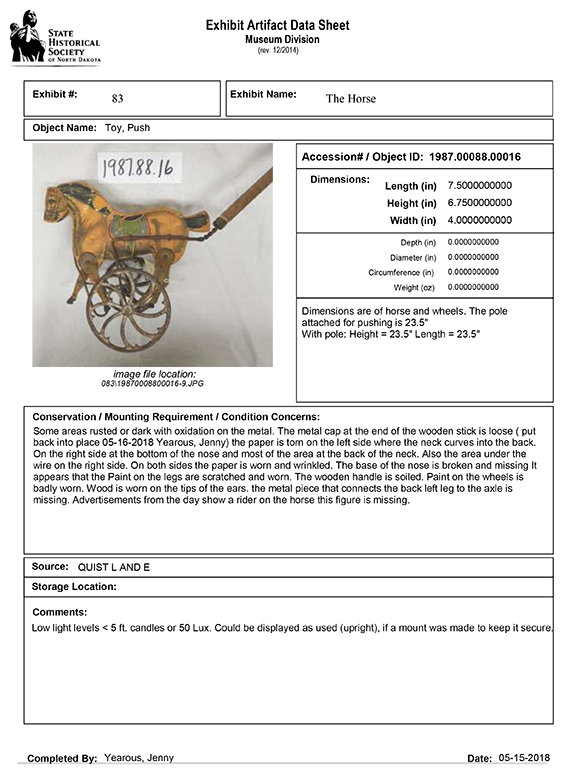

A condition report, which is a written description and visual record of an artifact’s condition, is completed before the object goes on exhibit. All defects are described, measured, and photographed. We look for fading, cracks, tears, deterioration, missing parts, chips, and any other types of damage depending on the artifact’s material make-up. Once an artifact comes off exhibit, condition reports are completed again to determine whether any changes occurred while it was on exhibit.

A Word document produced directly from our museum software database program. Click image for larger view.

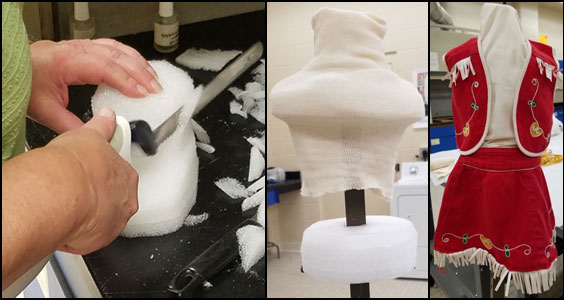

Some of the objects selected for The Horse in North Dakota will need to have custom mounts created. These mounts may be soft mounts, which is Coroplast (corrugated plastic) covered in cotton batting and cotton muslin. They could be made out of Plexiglas, or they may be mannequins. Sometimes we make our mannequins from scratch. We use metal rods for the stand, Ethafoam (a closed cell polyethylene material), and either cotton muslin or cotton stockinette.

Jenny Yearous, Curator of Collections Management) carving ethafoam into a neck and shoulders with an electric carving knife. B. The neck and shoulders covered in stockinette, and the ethafoam waist. C. Finished mannequin with children’s Cowgirl costume (2017.66.11-12).

Come see all of these artifacts and many more in The Horse in North Dakota starting August 25th! Let us know how many hours you think the collections staff spent getting the artifacts ready for display.

Jessica Rockeman is a New Media Specialist for the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Her duties include web, graphics, print, ND Studies materials, film and photography. She can often be spotted at the museum with a camera.

Jessica Rockeman is a New Media Specialist for the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Her duties include web, graphics, print, ND Studies materials, film and photography. She can often be spotted at the museum with a camera.