A Day without History: How your personal history connects with a larger historical narrative

Imagine waking up each morning with amnesia. No recollection of what you like and don’t like. No memory of what matters to you. Do you practice yoga or cook a big breakfast for your family? Do you go to church or pack for a vacation? Do you have a random job or are you on a specific career path? How would you go about your day if you didn’t have the accumulation of personal knowledge that makes you “you?” This is what it would be like to wake up one day without the identity our personal history provides us. Imagine a day without history.

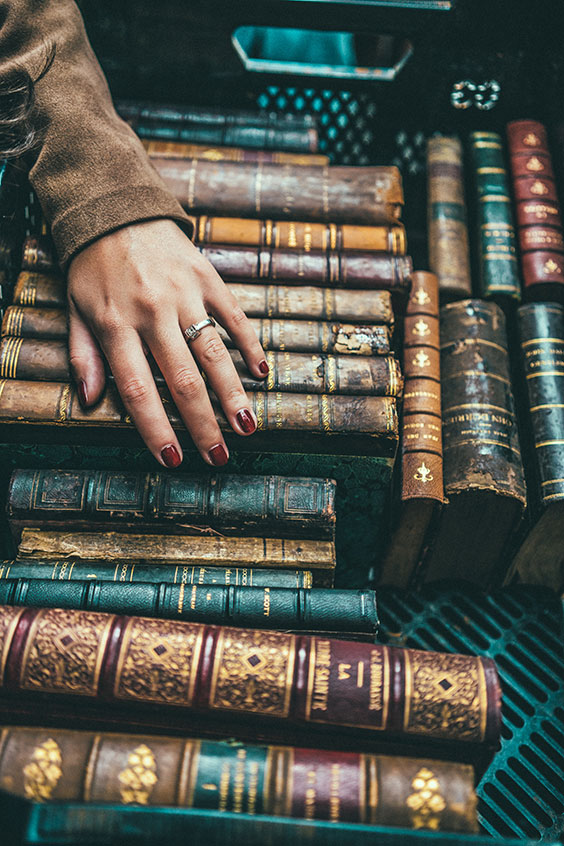

Our personal belongings help tell the story of who we are individually and how we are part of larger communities. Photo by Jason Wong on Unsplash

Everything has a history, including us. Your individual story, as well as that of your family, your community, and your country influences every decision you make each and every day. Experiences and memories serve as the building blocks of our identities, but our story is much more than that. It is an accumulation of who our family members are; our relationships with relatives; the family stories we’ve heard; our genealogies. These all contribute to what we know about our personal and collective history. How our family history fits into a larger community history and a larger historical narrative is just the beginning.

Family photos and other documents are an important source of the historical record. Photo by Mr Cup / Fabien Barral on Unsplash

In order to understand all the ways history affects our lives, it is important to follow the work of historians who work in colleges, museums, and other organizations. By reading the books they publish, listening to the stories they tell, and attending programs and exhibits they develop, anyone can learn how to tap into a deeper understanding of this history. Studying history helps us understand not only how the past affects the present and future, but also the larger picture of how society works. It tells the story of the human experience and helps us understand our individual purpose. History tells the story of our own lives. It helps provide us with an identity.

Staff at the State Historical Society of North Dakota is closely involved in this important work throughout the state. We do research, write papers, publish books and articles, develop exhibits and programs, document personal histories, and teach other people how to do this work themselves. We can talk to students about the work we do, and we can show you how to come to the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum or some of our state historic sites and do your own research. We want to help you discover all the fascinating and unique stories that together make up the history of North Dakota.

The work of historians through books, exhibits, and programs tells a story about our world that connects us all to each other and makes history relevant to us all. Photo by Fred Pixlab on Unsplash

History is all around us. It helps anchor us within our larger community and country. It connects us to one another. It is inseparable from who we are as people. The work of history professionals, including those of us working at the State Historical Society, can help you better understand your own personal story. The study of history is relevant to our daily lives. Just try to imagine who you would be without it.