Due for a Teeth Cleaning?

Working as a collections intern in the Museum Division this summer, my major project was to inventory the dental/medical collection in storage. This entails updating and cataloging records already in the database, photographing the objects, and then relocating them to areas of storage where they can be better organized. Although the collections I worked with were accessioned and catalogued in the 1950s and 1960s many had not gone through another full inventory since that time. Also, cataloging practices have changed over the last 60 years, particularly the numbering system and arrangement of objects within the collection.

During my second week, I started to inventory the first shelf which, according to the database, held seven objects. One of these objects turned out to be a bag full of 55 dental utensils, all of which needed to be cataloged individually and given object identification numbers. This soon became the trend for the dental collection, in which I have turned seven previously cataloged entries into 300+ individual entries. I can now say that I am well versed in the names and functions of various dental utensils.

Left: Assigning new object identification numbers to each utensil

Top Right: Case of 127 dental utensils used by C.C. Hibbs in Carson, ND. SHSND 13308.00128

Bottom Right: Dental utensils in storage after inventory completion

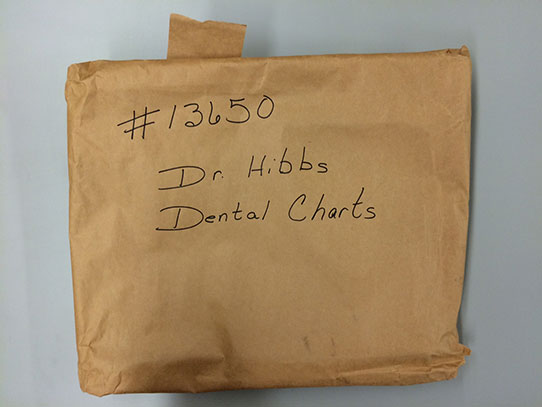

One of the more enjoyable aspects of working in collections is being able to handle objects that you know have a story. A large portion of the dental collection was donated by Charles C. Hibbs in the 1950s, but there wasn’t much information about him, his accomplishments, or the significance of his collection. It wouldn’t be until week nine of this project that I would come across a wrapped, brown package with “Dr. Hibbs – Dental Charts” written on the outside. Within this package were 21 paper items, which then of course had to be cataloged individually. Amongst the documents in this package was a letter written to the Louisville College of Dentistry Alumni News. This four-page document, written by Hibbs, outlined his career and major successes as a dental surgeon in North Dakota. I finally had a primary source, giving place and importance to the collection I had worked with over the previous eight weeks.

Brown paper package with 21 paper items inside. SHSND 13650

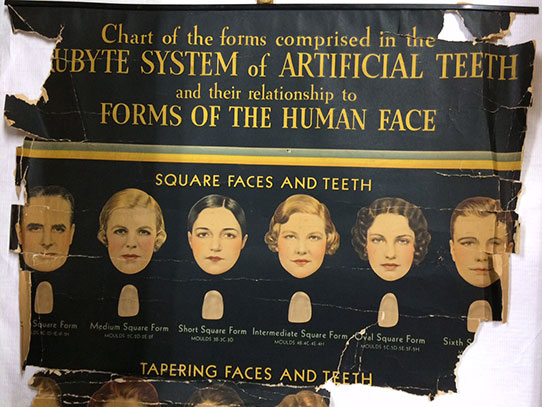

Dental chart showing the relationship of tooth shape with the form of the human face. SHSND 13650.00021

As it turns out, C.C. Hibbs was one of the first dental surgeons in North Dakota. In 1907, he rented space in a newly constructed building in downtown Bismarck for $20 per room. His offices were the first in the state of North Dakota to be used strictly for dental purposes. One of Hibbs’ major accomplishments was creating roofless dentures. He had studied the idea for years and, after losing all of his upper teeth, he experimented on himself. As he notes in his letter, “Now lets get perzonal, I am the only dentist in No. Dak. that makes roofless dentures.” Hibbs was in his eighties when he wrote this letter and exclaimed that he could still be in practice for another ten years if his eyes didn’t fail him.

Aside from learning more than I ever wanted to know about dental scrapers, scalers, probes, root extractors, elevators, etc., I was able to make major improvements to the storage condition of the dental collection, while filling in essential information as to why the museum accepted this collection more than 60 years ago. The physical objects are often thought of as the quintessential part of the museum collection, but the story behind them is often just as substantial as the objects themselves.