You have what? Adventures in Mount Making

Exhibits are one of the most visible ways that we, as a museum, engage with the public. Since reopening in November 2014, hundreds of thousands of people have passed through the galleries to see some of the treasures of our state, while also learning a bit about North Dakota’s history. I see exhibit development as one of the most important things we do as museum professionals. As a collections curator, it is also one of the most challenging.

I am the primary staff person who prepares artifacts for exhibit. The toughest part about it is finding a balance between artifact preservation and visual aesthetic. Some items are simple; lay them on a shelf and they’re happy. Others require quite a bit of creativity on the part of multiple people to come up with a workable balance. I’d like to show you the work involved with one artifact currently on display in the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum.

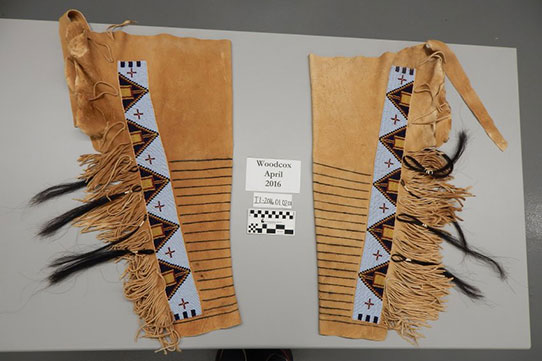

The artifact, a pair of hide leggings, was one of the more challenging items I prepared for the Native American Hall of Honor exhibit, which opened at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum on June 2. They are both fairly soft and very flexible, and being made of hide, they can’t be sewn through. Because of that, there were very few points where I could attach either legging to a mount. They are also heavy and require a structure that is sturdy enough to support their weight. I also needed to use archival materials that won’t harm the artifact over time. The final element is the visual aesthetic—how do you stay within the constraints of all of the above while creating something that looks natural?

Here are the leggings that were to be mounted. Made of soft hide, they would not stand up without being secured to a solid mount.

We have a large amount of cardboard tubes, and I decided to combine two for each mount, with a narrower tube at the bottom and a wider one at the top to replicate the general proportions of a leg. The leggings were created specifically for someone, so I wrapped archival foam sheets around the cardboard and layered them until the mount fit snugly and naturally into the legging, just like the leg they were meant for. I then secured each layer in place with strips of mylar, held together with double sided tape. To give the mount a more finished look, I wrapped undyed muslin around the top as well as a foam plug I cut to fit into the round hole.

The base of the mount I made was cardboard tube that we had left over from rolls of foam, tissue paper and other archival materials that we commonly use in the course of our work. I used a wider tube on top and a narrower tube on bottom, then wrapped sheets of archival foam around the tubes to match the proportions of each legging. The top of each was wrapped in undyed muslin to provide a finished look.

The leggings were to be displayed in a standing position. Without securing the leggings at the top, they would droop and slide down the mount. I would never try to sew through the hidesewing would cause damage to the material. There was one point on top where I could tack the legging to the mount, and that was a small hide strip that joins the two halves of material on each legging. I looped embroidery floss around the strip and into the muslin four separate times for strength and to spread out the weight as much as I could.

The finished product on display in the lower right.

Mounting the leggings was one of the more challenging parts of the exhibit for me. Most visitors probably won’t notice the final product, but that is the point of a successful mount!