Dealing with the Marquis de Mores’ Anti-Semitism at the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site

For many years, the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site has largely downplayed some of the more controversial aspects of the de Mores story, namely the Marquis’s anti-Semitism. Most of this comes from the fact that the Marquis’ anti-Semitism seems to have manifested itself after the family left Medora in 1886. From the beginning, the site has focused mainly on telling the story of the family’s life in Dakota Territory. However, as the years have passed and with the last of the family gone, the site has become the repository for the full history of the de Mores family. Because of this, our interpretive duties have evolved to tell their post-Dakota Territory story as well.

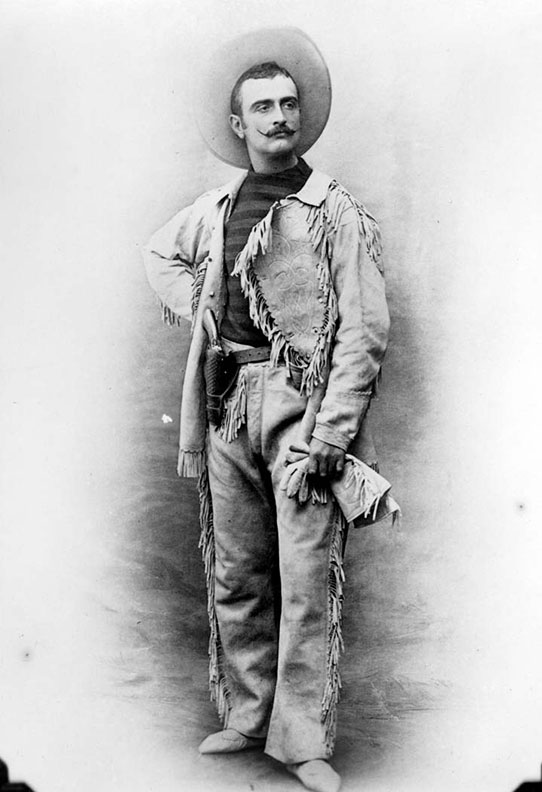

A photo of the Marquis taken in France in 1889 during his political years.

It is important that while we do not shy away from discussing uncomfortable topics like anti-Semitism, we need to be careful about how we address it. This begins with proper training for all site employees. The interpreters need to be ready and able to talk to the visitors about what happened to the family after they closed the house for the final time in 1886. This naturally means the Marquis’s duels, political career, and death, much of which revolved around his anti-Semitic rhetoric and beliefs. After the Marquis returned to France, he became involved in politics. He supported anti-Semitic candidates and often spoke at rallies. The Marquis was also a frequent contributor to several anti-Semitic journals. An article in one of these journals led to one of the most famous episodes in the Marquis’s short life, his duel with Camille Dreyfus. Dreyfus, a Jewish government official, wrote an article in the journal La Nation attacking the Marquis’ anti-Semitism. The Marquis promptly challenged Dreyfus to a duel. Dreyfus accepted, and the duel took place on Feb. 3, 1890. Neither the Marquis nor Dreyfus was seriously hurt in the duel, but the Marquis shot Dreyfus in the arm, winning the duel. The Marquis’s death can also be viewed as an extension of his anti-Semitic activities. The Marquis’s reason for being in North Africa was to unite the Muslims against the Jews and their “British puppets.” It is ironic he was killed by the very Muslim tribesmen he was trying to recruit.

These are topics we address but do not dwell upon. However, the interpreter must be able to discuss the topic further if asked. It is the job of the site supervisor and assistant site supervisor, in spring training and morning meeting discussions to prepare the interpreter to speak intelligently and with sensitivity. Store employees, usually the first ones to interact with a visitor, must be as able as any interpreter to answer questions.

Technology has opened up new ways to enhance and add information to the tours. The site is currently using QR codes in several locations in the Chateau. This technology is inexpensive and easy to create. The possibilities with QR codes are almost limitless, providing graphics, text, and audio/visual resources on the visitor’s cell phone without intruding on others’ tour experiences. This allows topics like anti-Semitism to be addressed in a more in-depth way for those desiring additional information. Another technology the site uses is our eight-minute video. This free video is used at the interpretive center to provide some context for understanding the history of the site and the de Mores family. The video also discusses the Marquis’ background and personality, providing further background for the controversial views he expressed later in life. The video can be updated as we see fit. This is important because the video may be the only site information source for visitors.

As museums and historic sites become more willing to address darker issues in the past, sites like the Chateau have examples and advice for how best to open the door on these subjects. If done carefully and sensitively, confronting the more unsavory aspects of a historic site can lead to a more complete understanding of our past.