Celebrating Archives Around the Country

I love a good celebration. Holidays and parties are all fun, whether it’s the Fourth of July, your birthday, or Talk Like a Pirate Day (this last was September 19, this year).

Well, here is something more to celebrate—you get to read an Archives-related blog post during American Archives month!

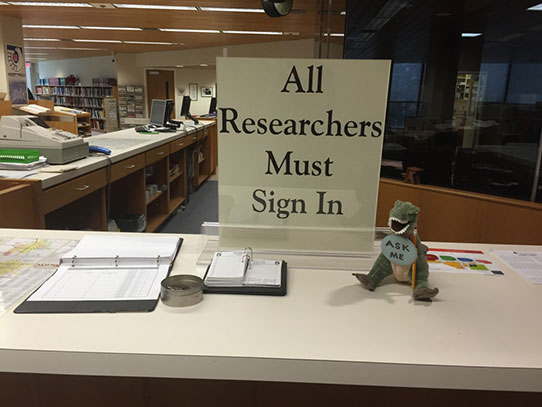

The entrance to our State Archives welcomes researchers, and provides an outline of rules for the Orin G. Libby Memorial Reading Room. Rodney, our dinosaur, is getting into American Archives month, but as far as I have seen, no one has asked him any questions.

Every year since 2006, the Society of American Archivists (hey, what do you call a group of archivists?) hosts a month-long, educational celebration for archives around the country. Archives (local, state, and federal all included) can use this month to remind and inform people about what an archives is, what records can be found and stored there, what sort of research can be accessed there, and more. The Society of American Archivists has some great resources available on their Web page. The Council of State Archivists also has some good links, which can be accessed here.

Within American Archives month is another special day of note, this one sponsored by the Council of State Archivists—Electronic Records Day (it was October 10, this year), which is currently in its fourth year. This day is meant to raise awareness about what place electronic records hold in the world. This year, E-Records Day is highlighting the importance of appropriate management of electronic communications in government. Some more great sources are available here on their Web page.

One way that some state archives participate is by sending out informational pamphlets, posters, and bookmarks in honor of this month, or by placing something informational on their website. Typically, this includes featuring something from their own archives (such as this poster from Montana, this bookmark from North Carolina, or this web page in South Dakota), or displaying information on Archives policies (like this fun poster from Pennsylvania, which you really should check out…learn why our collections should be treated like your Aunt Edna).

So in celebration of all this Archives love, here is a brief display of some items of interest from our own State Archives. These items, mostly scanned photos and documents, display a few moments captured in time. These are preserved through archival practices and thus are saved for our future generations.

Oh, and by the way—I’d call a group of archivists an archives. An archives of archivists.

Photographer Frank Fiske was a native of the Dakotas who photographed many images of people and events around the Standing Rock Agency in and outside of his studio there. Here he has photographed some unidentified Indians who are drumming and singing. (SHSND 1952-00448)

Fannie Dunn Quain, a female doctor from the late 19th century, was the first North Dakotan to enter and graduate from medical school, and would later help to start the first “baby clinic” in the state. In this image, she, along with other prominent North Dakota women, served on the first all-woman jury in North Dakota in July 1923. (SHSND 00091-00243)

This image of a small boy in a tractor comes from a collection consisting of images of family and of a dairy owned by the Gessner family around Penn, North Dakota. (SHSND 11091-00001)

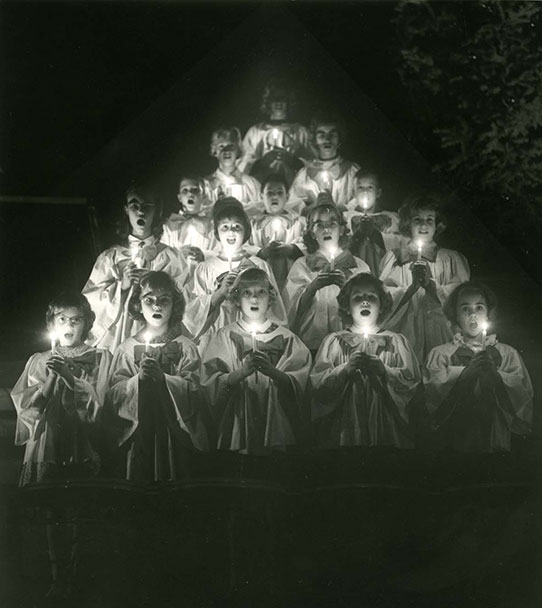

The very large (approximately 153 linear feet) William E. Shemorry Photograph collection consists of images and office files of Shemorry, who reported, wrote for, and photographed for newspapers, snapping images of people and events around the Williston area, such as the First Lutheran Junior Choir pictured above. (SHSND 10958-1-52-8)

This image was taken circa 1958, and shows chairs and the setting at the Custer Memorial Amphitheater in Mandan, with actors of the Custer Drama “Trail West” in the background. (SHSND 00053-00006)

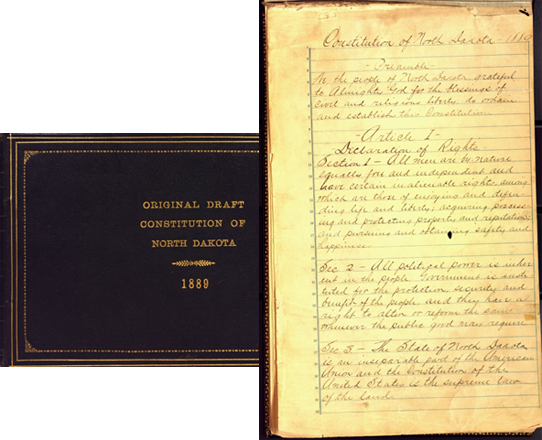

The cover and first page of the original draft of our ND state constitution (SHSND 31372)