North Dakota Passport: A New Way to Explore 37 Featured Destinations

When was the last time you paused on a scenic trail to admire the sights and sounds of nature? Have you truly reflected on the significant people of our past while standing in a historic place?

The State Historical Society of North Dakota and North Dakota Parks & Recreation Department recently teamed up on a project to help residents and out-of-state travelers make the most of their visits to recreational and historical sites throughout the state. Taking on this project while in the middle of a pandemic made us think about things a little differently than we might have otherwise. We decided the way to go would be to promote road trips to destinations with outdoor sights and activities.

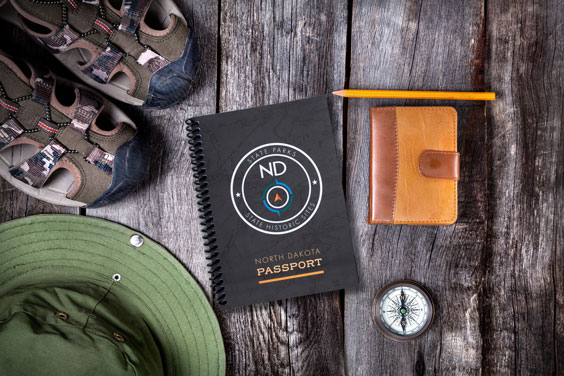

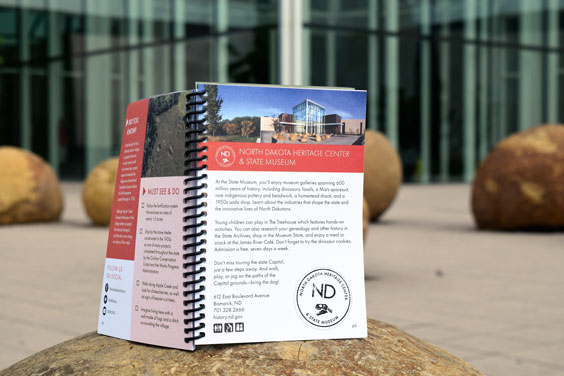

The next step was figuring out what the end product would be. What we came up with is the North Dakota Passport, an 88-page book featuring 37 destinations. At each location, participants can get a unique stamp. All but one of the locations in the book have an outdoor Passport Station where visitors can transfer the stamp to the book by rubbing on the page with a crayon. The North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum’s Passport Station is located indoors. Staffed locations also have a stamp available indoors.

Because North Dakota’s weather can be unpredictable, we went with durable, waterproof paper for the front and back covers. The inside pages are also a bit thicker than your average paper to hold up better when transferring the stamps at Passport Stations. We chose a spiral binding, which makes the pages nice and secure while allowing them to be fully turned.

We wanted it to be easy for people to carry the books around while exploring, so a drawstring backpack is included with the purchase of a North Dakota Passport. We also added a package of crayons, since we didn’t want people to arrive at a Passport Station with no way to transfer the design to their book.

Each location listed in the book includes background information, amenities, pictures, contact information, social media handles, must-see-and-do activities, and a fun fact or two.

This project was very collaborative between the two agencies—from design to text to marketing and everything in between. The staff at Parks & Recreation were great to work with, and I look forward to partnering with them on more projects!

Where will you visit first? My first stamp is from the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum since I work there, but I can’t wait to collect them from all 37 state historic sites and museums, state parks, and recreation destinations! Share your adventures on social media using #explore701.

To learn more and purchase your North Dakota Passport, visit parkrec.nd.gov/passport.