Hands-on History: The Do’s and Don’ts

We’re starting a project, called Hands-on History, to make history more immersive and multisensory at our staffed state historic sites. We want to give visitors more opportunities to learn by doing historically accurate activities, like trying on unique historic clothing, playing games, or using period technology.

It’s funny, though. Year after year I see articles, books, and conference presenters urging us to offer more interactive learning, but precious little advice about how to do it. I have received a ton of training on how to give tours, research history, write exhibit panels . . . so why is there so little out there about hands-on experiences? This means that over the last decade or so, I’ve had to just try things and see what worked. Here’s a little summary of what I’ve learned:

Soon numerous state historic sites will have stereoscopes, a 19th-century 3-D viewer, with images from the State Archives.

1. Do start with research.

This is where the most interesting and historically accurate ideas come from.

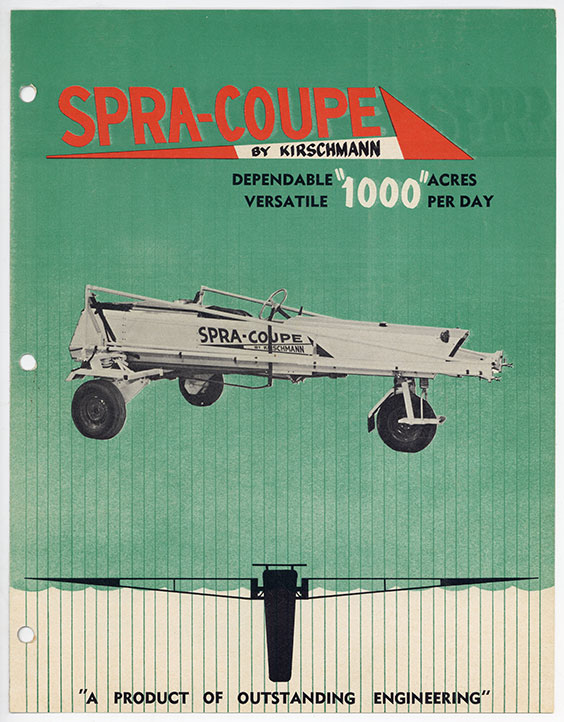

2. Do make your objects as close to original as possible.

You want the closest replica of the historic object you can get, within the limits of durability, repairability, or replaceability.

3. Do be excited.

If you’re offering an experience you’re excited about, your visitors will be, too.

At the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site, Addilyn Groven got to launch her own (non-nuclear) rocket.

4. Do connect your object to an important idea.

Ideally the experience helps people understand the significance of your historic site. Since the visitor should have new insights from the experience, we can ask thought-provoking questions. (Was it possible to write with your left hand using an inkwell and a quill pen? If you were a schoolteacher at the time, how would you teach your left-handed students how to write?)

It must be said, though, that sometimes it’s okay to just offer a fun, historically-accurate experience that makes people feel more at home at your site.

5. Don’t think of hands-on history as an add-on to your “more important work” of conversing about history.

This attitude often causes us to treat visitors who may seem less interested, such as children, as if they are less important than the visitor who is already engaged and asking lots of questions. We have to serve the needs of all our visitors.

Science toys are nothing new. In the 19th century, a zoetrope helped kids learn about optics and moving images.

6. Don’t just give visitors something to touch.

Maybe you’ve observed this strange tendency, but the minute you give people permission to touch something at a historic site, their desire to touch it goes way down. The real fun starts with doing something. And not just anything. Which leads me to . . .

7. Don’t give your visitors historic work to do.

If it wasn’t fun in the past, it isn’t fun now.

It may seem like a cheesy photo op, but clothing illustrates a lot about cultural values, social roles, and the work different people had to do.

8. Don’t make assumptions about who will or won’t try an experience.

I googled “why I hate museums” once, just to see what I might learn. One reason came up in multiple articles and really surprised me: people hate it when all the fun experiences are just for kids.

9. Don’t waste too much effort on experiences you can only offer at special events.

You can provide far more experiences — ones that require lots of set-up and clean-up, or a guest expert, etc. — if you offer them as special events. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. But you’ll reach far more people if you develop experiences that visitors can try every day.

In the Attic Playroom at the Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site, kids can play with toys typical of the years 1901–1960, the same time period the room was used by several governors’ children.

10. Don’t always expect your visitors to initiate the experience.

There’s so much confusion these days about what you can and can’t touch and do in any given historic site or museum. Visitors may need some active encouragement to try out new activities.

11. Do help visitors succeed when trying a new skill.

Make sure you know how to accomplish the task yourself, and look for opportunities to improve the experience so visitors succeed in their attempts to try it.

Kids used old steel wagon tires and later wooden or cane hoops for a wide variety of games called hoop trundling. These hoops eventually evolved into the hula hoop.

12. Do understand that there can be risks.

I’ve actually seen more injuries, such as heat exhaustion and passing out, on tours than during hands-on history experiences. Still we have to design these experiences to be reasonably safe and sometimes guide visitors to perform activities a certain way.

13. Do be appropriate.

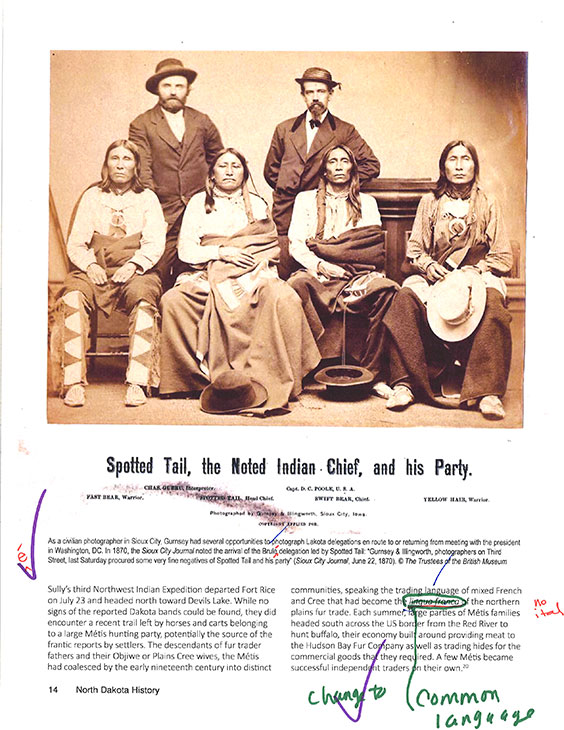

It would not be culturally appropriate for visitors to try experiences that one must earn the right to perform in the original culture or context. We won’t be offering visitors the chance to try on warbonnets or medals of honor. Likewise, it’s disrespectful and wrong to try to replicate traumatic experiences. And yet . . .

14. Don’t pass over important cultures or communities.

It takes time, effort, and engagement to learn how to represent a group fairly, accurately, and appropriately, but it’s also essential to telling a balanced story.

Sophia, like countless young girls stretching back centuries in North Dakota, learned how to lace up a tipi with wooden pins.

There are so many great reasons to do hands-on history. It makes history more enjoyable. It’s more accessible to children, people with disabilities, people who don’t speak your language, and people who otherwise might not visit historic sites and museums. Visitors learn more by involving multiple senses (taste, feel, smell, sound, sight, texture, temperature, etc.). They remember more, too. They’re more likely to take pictures of their awesome experience and share them with their friends. It gives them a reason to visit in person rather than only learn online.

I’m excited to watch this area grow, especially right here in North Dakota. Some of our Hands-on History experiences are already available at staffed state historic sites around North Dakota, and we will be adding more and more as time goes by. We hope you come try them out!