Researching Military Ancestry at the State Archives

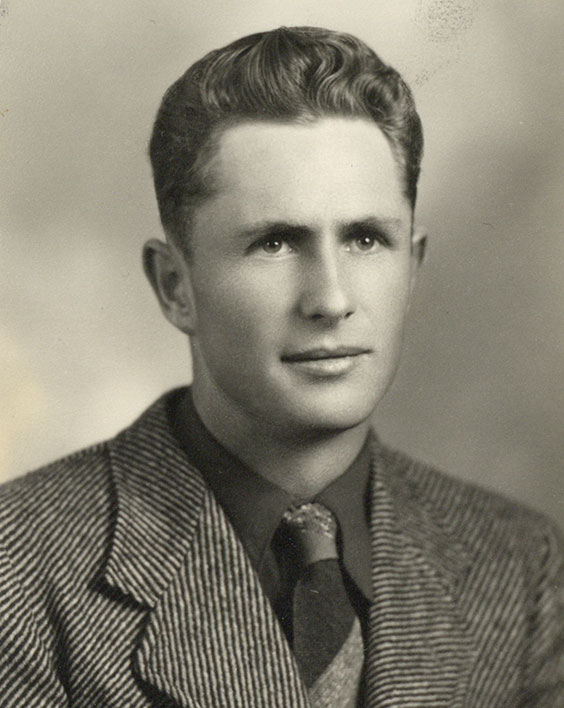

Though summer is winding down, the State Archives is still buzzing with researchers on vacation, in addition to our regular local patronage who come in throughout the year. Students, scholars, and curious citizens come to examine our collections to answer their diverse questions. Genealogy remains an area of strong interest, and one question often asked is, “Where can I locate my ancestor’s military record?” While we do not have service records for individual veterans unless that person or their family donated them to us, we do have resources to help patrons in their search and places we can direct you to attempt to answer questions.

How can the Archives help someone research an ancestor’s military service? In our stacks, we have books related to military history, including unit histories, general works on wars and conflicts the US military has been involved in (with a focus toward those North Dakotans participated in), and published diaries, memoirs, and letter collections. These may be useful if a researcher knows the unit(s) their ancestor served with and wants to know where they may have been during a war.

A selection of State Archives books related to World War II.

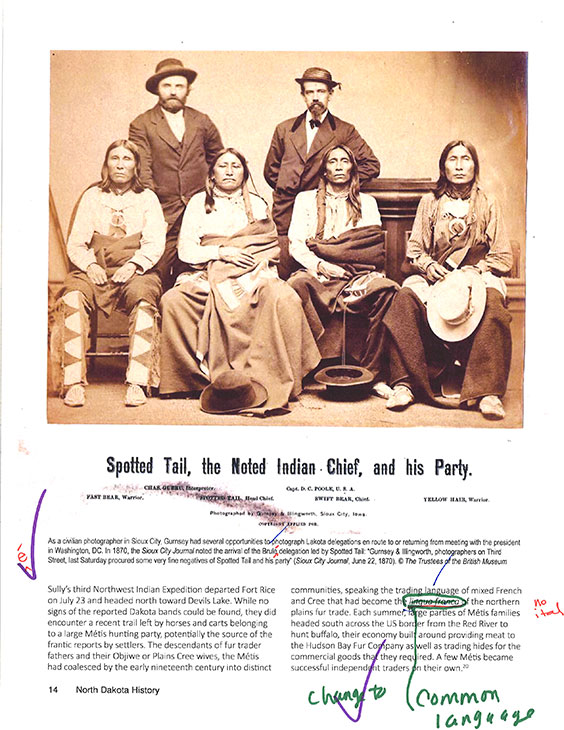

We also have a surprising number of regimental histories for units raised during the Civil War, which provide the roster of the men who served in that unit, as well as detailed accountings for the places they passed through and battles they fought in during the war.

We also have a nice selection of books produced by North Dakota counties on residents who served in World War I. These books are helpful to a researcher, as they usually go beyond a simple listing of the men and women from the area, providing stories, photos, and news related to the county at that particular time.

Examples of our North Dakota county World War I holdings.

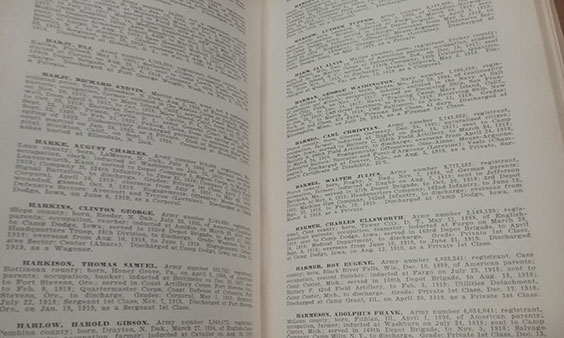

A valuable resource we have both in print and on microfilm is Roster of the Men and Women Who Served in the Army or Naval Service (including the Marine Corps) of the United States or Its Allies from the State of North Dakota in the World War, 1917–1918 (1931). This four-volume set lists the North Dakota veterans of World War I and provides a nice, paragraph-length entry on each person that can help a researcher understand a little of their ancestor’s service. A similar roster exists for World War II and Korean War veterans that is commonly called “the red book” because of its red cover. Its entries are not as detailed as its World War I counterpart. It is also available to access through both print and microfilm in our reading room.

Pages from Roster of the Men and Women Who Served in the Army or Naval Service (including the Marine Corps) of the United States or Its Allies from the State of North Dakota in the World War, 1917–1918.

In addition to the holdings in our stacks, we have several collections of federal records related to military posts in the state during the 19th century available on microfilm. These include some muster rolls and medical histories. A full listing can be found here by scrolling down to War Department. The records are housed in the National Archives and don’t provide a detailed accounting of an individual soldier’s life, but more a snapshot of a unit at a particular point and time.

For persons who served in the North Dakota National Guard, while we do not have personnel records, we have a sizable collection that contains a variety of records related to several components of the Guard and can inform a researcher as to an ancestor’s service.

Local newspapers provided varying levels of coverage on local men and women serving in wartime, including publishing letters written to inform the folks back home. Finally, researchers have access to Ancestry Library Edition on our research computers that contain several great databases related to military research, including draft registrations, pension indexes, and service indexes.

Our reference staff can also help point you toward sources to consider when researching your ancestor’s military service. While the State Archives may not have records related to every individual veteran from North Dakota, we have ample resources to help you learn more about military service in your family. Stop in with your questions, and we will do our best to answer them.