The Failed Fisk Expedition: What If??

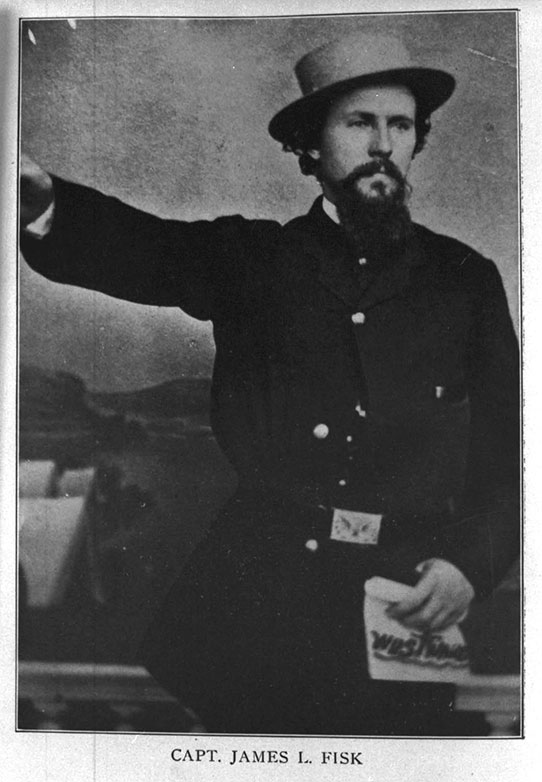

Captain James L. Fisk, SHSND

“A strong camp and picket guard were posted for the night—a cold lunch was passed around at nine o'clock, and then some tried to sleep. But soon the night darkened into blackness. Hundreds of wolves, attracted by the scent of blood and of corpses set up a most unearthly howling and yelping, while there gathered and broke over us a thunder storm more grand and terrific than anything I had ever experienced. There was incessant and intensely vivid lightening for nearly an hour, and then came peal and treble peal of heavy continued and incessant thunder which lasted for two hours. A shower, not in drops but in sheets poured for an hour upon our parched camp, till within the corral, in the natural basin around which it was formed, cattle were standing in the morning in two feet of water. The fatigue of the day, the groaning of the wounded, the howling of wolves, the unprecedented storm under such circumstances made this a night in my experience never to be forgotten.”[1]

James L. Fisk,

Dakota Territory

September 3, 1864

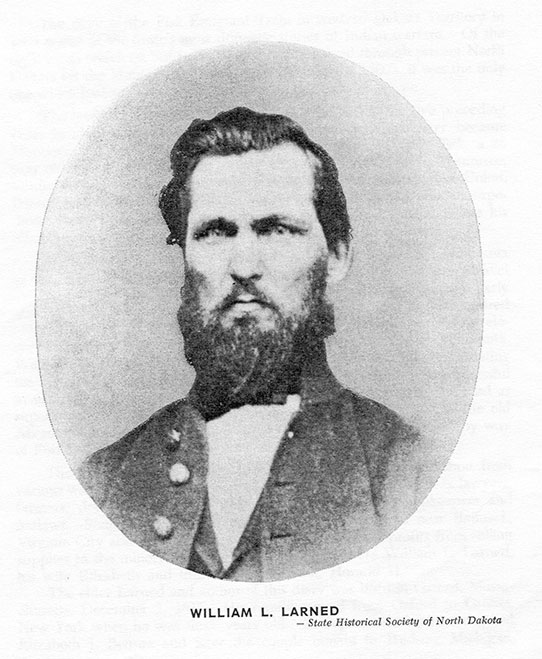

William L. Larned, Emigrant member of the 1864 Fisk Expedition, SHSND

+++++

“To gain a little personal fame he (James L. Fisk) has thrown the train to the south of a route already open & well defined by Gen. Sully under the guidance of the most competent guides, & has been pushing ahead through a rough broken country of which he is utterly ignorant & his engineer often unable to set on his horse from intoxication…. Yet I like him for his good nature covers a great many defects.”[2]

William L. Larned,

emigrant member of the Fisk expedition,

September 10, 1864

+++++

Hubris, poor planning, and bad luck had followed the emigrant train to this point.

I began this story in my last blog post, [http://blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/troubled-time] and quotes like those above are the reason why I enjoy doing research in the State Archives at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum (http://www.history.nd.gov/archives/index.html). Publications sometimes leave out the gritty details and personal anecdotes of the participants in historical events. Additional searching adds context and substance to some of these stories. Personally, I find it fuels the “what ifs” of history.

For instance:

The Fisk emigrant train spent seven days at Fort Rice awaiting and completing passage over the Missouri River aboard the steamboat U.S. Grant. If they had departed Fort Rice even two days later, would they have steered clear of Sitting Bull and his warriors?

Sitting Bull, SHSND

Conversely, if the emigrant train had departed Fort Rice a couple of days earlier, would they have been bogged down in the rugged terrain of the Badlands and put at risk of total annihilation by the Hunkpapa (Lakota) warriors?

Sitting Bull was shot in the left hip during the Fisk raid in September 1864, when a band of Hunkpapas attacked the Fisk wagon train. The bullet exited out through the small of his back and was not serious. How would history have changed if Sitting Bull had been killed during the skirmish?

After the siege, survivors from the Fisk emigrant train returned to Fort Rice. Some of the members of the aborted expedition remained at the fort over the winter and beyond. Is it possible that some of those travelers played a part in early Edwinton/Bismarck, Dakota Territory?

On July 28, 1865, Sitting Bull and his warriors attacked Fort Rice. This intense battle, one of the largest in the history of Dakota Territory, may have wiped out the fort if not for the superior weaponry of the “Galvanized Yankees,” the former Confederate prisoners-of-war stationed there. Would this attack have occurred if Sitting Bull had been killed eleven months earlier?

What if??

If you have not yet visited the State Archives, I invite you to do so. I am interested in your thoughts and research into the “what ifs” of the failed 1864 Fisk emigrant expedition.

[1] James L. Fisk to US Army Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, “Report of the Expedition (Northwestern) to Montana in 1864 for the protection of Emigrants under his Command,” 13 January 1865, www.fold3.com

[2] Ray H. Mattison, ed., “The Fisk Expedition of 1864: The Diary of William L. Larned,” North Dakota History 36 no. 3 (Summer 1969): 209–74.