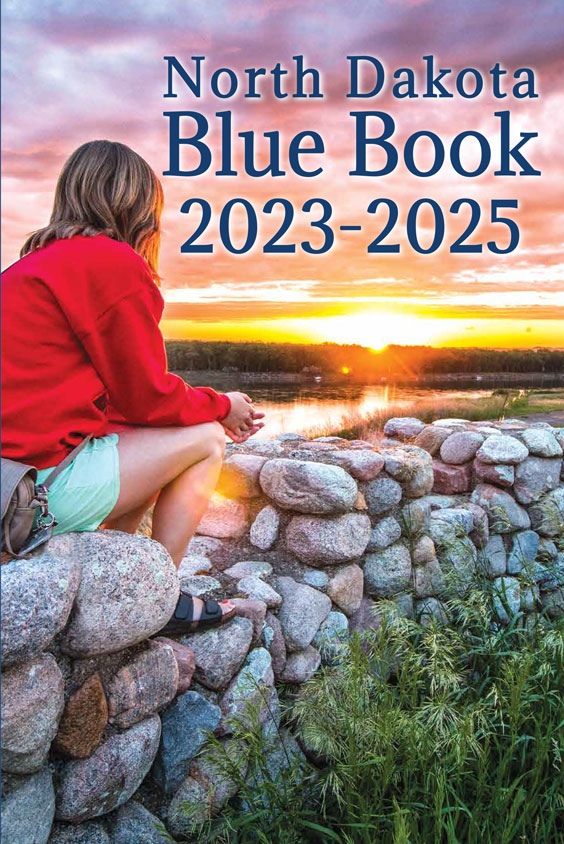

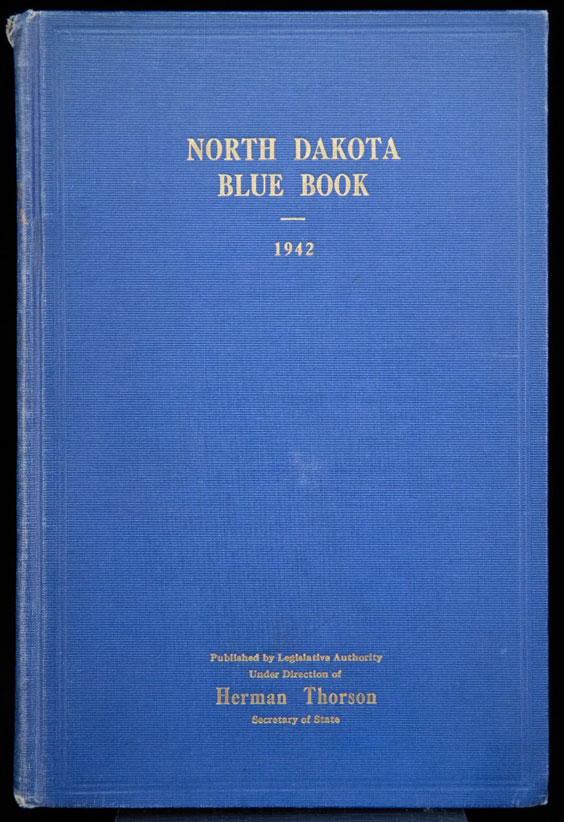

When the 2023-2025 North Dakota Blue Book is unveiled in a ceremony this Wednesday at the state Capitol, the event will mark the culmination of a two-year effort by the secretary of state’s office, other state employees, and volunteers to compile what Gov. Doug Burgum has called “a treasure trove of information about all things North Dakota.”

Double Ditch Indian Village State Historic Site outside Bismarck is featured on the cover of the new North Dakota Blue Book.

Secretary of State Michael Howe said the biennial Blue Book, published by his office, depended on “a multitude of folks that care about the history of North Dakota.”

For Audience Engagement & Museum staff at the State Historical Society, our involvement began in October 2022 when Clearwater Communications, which coordinates the effort, contacted department director Kim Jondahl to let her know the Blue Book Committee had selected North Dakota state historic sites as the featured chapter topic.

Over the next three months our team got to work. Kim put in countless late nights researching and writing the chapter with input from our state historic site managers and supervisors. Editor Pam Berreth Smokey and I condensed and edited text. Meanwhile, New Media Specialist Supervisor Angela Johnson sourced images to accompany our contribution.

The result, a 50-page chapter providing an up-to-date overview of the state’s 60 state museums and historic sites, underscores the “power of place … [to connect] us to the world around us,” according to State Historical Society Director Bill Peterson, who will speak at the Blue Book launch. The chapter traces the agency’s evolving relationship with these sites, from the purchase of the first state historic sites in the early 1900s to the ways the state continues to steward and develop these significant locations today.

In addition to the featured chapter, the Blue Book, the 38th since statehood, includes a wealth of reference material on North Dakota’s branches of government, elections, natural resources, educational system, tribal-state relations, and key industries. A concluding chapter, penned by State Archives Head of Reference Services Sarah Walker, explores 150 years of Bismarck history in commemoration of the capital city’s sesquicentennial celebration in 2022.

All 141 state Legislators, cabinet members, elected officials, university presidents, the State Library, and contributors will receive copies. Blue Books are also sold in the ND Heritage Center & State Museum’s store, with past editions accessible via the State Historical Society website.

The 2023-2025 Blue Book, which clocks in at over 600 pages, has come a long way since the slim 180-page inaugural 1889-1890 edition. That roughly pocket-sized volume comprised an array of political and official statistics, the North Dakota Constitution, and founding national documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. It followed a similar format to Long’s Legislative Hand Book and Rules of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Dakota, produced in 1887 and 1889 by Mandan attorney Theodore K. Long.

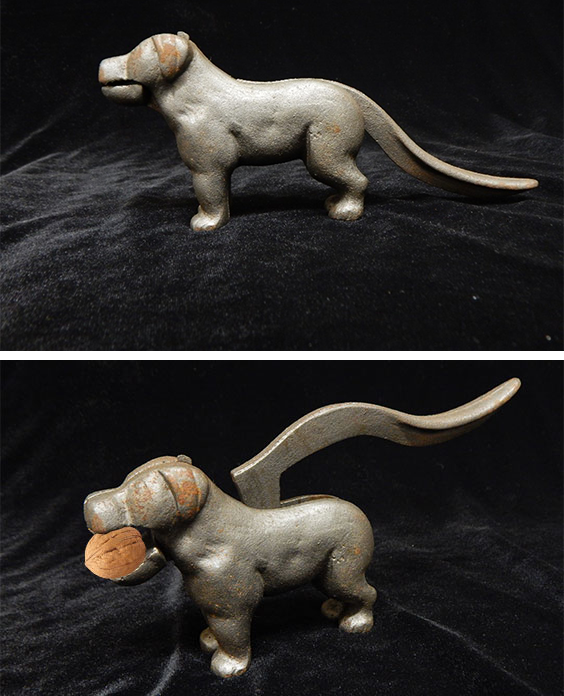

The inaugural, not so blue, Blue Book. SHSND SA 353 N811 1889/90

Interestingly, that first edition wasn’t even blue, nor was it called a blue book, a term adopted from the British who printed government reports and diplomatic correspondence in blue covers at least as early as the 1600s. The copy housed here in the State Archives has a salmon-colored cover—it wouldn’t go blue until 1897—and was known as the Legislative Manual. In the 1920s and 30s, the book was published under the title, the Manual for the State of North Dakota, before becoming officially known as the North Dakota Blue Book in 1942.

For much of the 20th century, the Blue Book was produced sporadically—about once every decade. But in 1995, Howe’s predecessor as secretary of state, Al Jaeger, began publishing it biennially. “All the credit I think goes to Al understanding the value of having that history in book form and also looked at every two years,” said Howe, a former state legislator who was elected secretary of state in November 2022 and in this role also serves on the State Historical Board. “Al since 1995 has been a part of every Blue Book including this current one that’s coming out.” Moving forward, the secretary of state’s office is exploring ways to expand the book’s digital format. They also plan to continue the tradition of printing the Blue Book (although exactly what that will look like is under consideration).

In the 1920s and 30s, the Blue Book sported a distinctly patriotic cover. SHSND SA 353 N811 1929

Over the years, while state government statistics and reference material have remained a staple of the publication, the information inside has varied—early editions included everything from postage rates and the value of foreign coins to the names of registered law students and a listing of insurance companies operating in North Dakota. Some editions even reprinted England’s 1215 Magna Carta, which famously limited royal power. And in the era before women and many minority groups received full voting rights, the 1909 Blue Book featured a section on the qualifications needed by state to vote. With some variation, the common requirement was that you be male and at least 21 years old.

For its amusement quotient, however, the 1942 edition is a standout. It not only notes the number of large candy factories in North Dakota (two in case you were wondering) but also gives space to then-Gov. John Moses’ thoughts on our infamous winters. Moses deemed these “sadly misrepresented” and “widely dramatized in the public press,” on average “no more than seven to fifteen degrees below those recorded at St. Petersburg, Florida.” Ahem.

Want the skinny on North Dakota candy production? The 1942 Blue Book has you covered. SHSND SA 353 N811 1942

If that wasn’t enough to make readers pack their bags and head our way, Moses ended his homage to the state by citing the words of North Dakota poet James W. Foley: “There’s something in Dakota … makes you bigger, broader, better, makes you … noble as her soil … makes you mighty as a king.”

The 2023-2025 North Dakota Blue Book will be launched from 3-4 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 13, by Secretary of State Michael Howe in the Memorial Hall of the state Capitol. The event, featuring musical entertainment, light refreshments, and remarks by officials, is free and open to the public. Contributors will be able to pick up their complimentary copies at that time.