A Cat Chat: 5 Cat Items in the State Museum Collections

In February 2024, my colleague Lori Nohner, research historian, wrote "A Dog Blog: 5 Things Shaped Like Dogs in the State Museum Collections." I thought it was time to give the cats their due. Here are five feline-related items from the State Museum collections:

1. Cream pitcher with handle shaped like a cat

Part of a collection of pitchers donated by North Dakota’s first licensed female physician Dr. Fannie Dunn Quain, this pitcher was made in Czechoslovakia in the 1920s. It looks like the spotted cat might want a sip of the pitcher’s contents. But first they want to make sure you are not looking.

1920s cat-handled cream pitcher. SHSND 1986.147.57

2. Cat stuffed animal

It is obvious that Marie Korth Wiik loved her kitty. The homemade, white flannel stuffed animal with shoe button eyes was gifted to her in 1912 around the time she was born. It was loved so much the cat is now bald. Its tail has been reattached, seams have been resewn, and stains reflect many years of being Marie’s best friend. Considering how dirty and worn the tail is, I wouldn’t be surprised if she carried the toy by the tail most of the time.

Well-loved stuffed toy cat, 1912. SHSND 1990.201.2

3. Kitten mittens

No kitten would lose their mittens if they were wearing this fuzzy pair of kitten mittens. Juanita Weinrebe (and likely her little sister, Donna) kept warm with these cute kitten mittens while growing up in Minot. Each tail holds a safety pin, so the mitten could be attached to the child’s coat and not lost.

Cozy kitten mittens, circa 1915. SHSND 1993.33.196

4. Cat-shaped hot water bottle

Cuddling up with a cat is a great way to keep warm. If you don’t have a real cat to cuddle, this cat-shaped Kuddle-Kitty hot water bottle made by Rexall Drug Company in the 1940s would be a distant second. Unfortunately, the rubber used for the hot water bottle is now hard and brittle making it less cuddly.

Kuddle-Kitty hot water bottle, 1940s. SHSND 1990.277.15

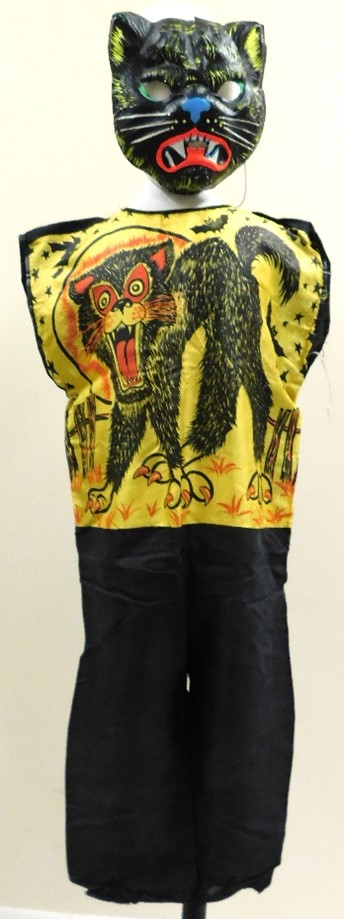

5. Black cat Halloween costume

For centuries, people have thought that black cats were the source of bad luck, making them a great Halloween symbol. This Halloween costume was purchased in the 1960s from the Johnson Variety Store in McVille by the Odegaard family. I hope it was lucky for the child as they trick-or-treated—at least it would have been a fun scare!

Black cat Halloween costume, 1960s. SHSND 2018.49.6